In April of 1984, Mark Pelczarski took a flight from Penguin Software’s home base of Chicago to San Francisco for the “Apple II Forever” event. Traveling with him were Steve Meuse, who had just written new extensions for Penguin’s graphics utilities to take advantage of the Apple IIe and IIc’s double-hi-res graphics mode, and Steve’s wife Marsha. Over the course of the flight, the three sketched out an idea for a series of computer games for “subversively” teaching geography, as had the old board game Game of the States and the perennial favorite Risk. By the time they made it to the Moscone Center to join the other Apple faithful, they had plans for no less than six games, one each for Europe, North America, South America, Asia, Africa, and Australasia. Each would have you traveling through its region of the world on the trail of a villain. Figuring out where your quarry was would require piecing together clues relating to the geography, culture, and history of the region. The Spy’s Adventures Around the World soon became one-third of Penguin’s grand strategic plan for the next few years, to stand alongside the graphics software and the new Comprehend series of adventure games.

Through that summer, at the same time that he was designing and implementing the Comprehend system with Jeffrey Jay, Mark worked with Marsha to put together a prototype. In the fall they refined it with the aid of some educational researchers, tested it out with actual classes of schoolchildren to see how well it held their interest, and hired artists to begin filling it with Penguin’s trademark colorful graphics. Meanwhile Mark developed a cross-platform database-driven engine to replace his original BASIC implementation.

As the work went on, and as has been documented in painful detail elsewhere in this blog, the software industry was becoming a more and more uncertain and dangerous place for a small company like Penguin. Mark therefore broached an idea to Doug Carlston of the larger and more diversified Brøderbund: would he be interested in acquiring Penguin, as he had recently acquired Synapse Software? It’s certainly not the sort of idea that any entrepreneur takes lightly, but Mark felt he had good reasons for approaching Doug — and only Doug: “Doug was by far the person in software publishing whom I most respected.”

The two went about as far back as colleagues possibly could in an industry as young as this one. Mark had first crossed paths with Doug before Penguin or Brøderbund existed, when he was working for SoftSide magazine and Doug was selling his first game through the magazine’s TRS-80 Software Exchange. Later, whilst they were visiting him at his home in San Rafael, California, Doug had introduced Mark and David Lubar to a hotshot programmer named Chris Jochumson who added animation to the Penguin graphical suite. Mark returned the favor at the West Coast Computer Faire of 1983 when an artist named Gini Shimabukuro approached him with a big collection of clip-art images. Not himself having any programs in the offing that could make use of them, he thought of Doug, who had just demonstrated for him an idea that would soon become famous under the name The Print Shop. Mark sent Gini over to the Brøderbund booth, and her art eventually became a big part of The Print Shop’s finished look. Working together, both men also played important behind-the-scenes roles in the founding of the Software Publishers Association to promote the industry, advocate for the rights of smaller players like Penguin, and rail against piracy.

When Doug expressed tentative interest in the acquisition, Mark flew out to California once again in January of 1985 with a briefcase full of financial reports and details of Comprehend and the Spy’s Adventures series. He shared all of that and then some with Brøderbund, including Penguin’s three-pronged strategy for the future. Doug and Gary Carlston and Gene Portwood listened with apparent interest. While they didn’t share the status of their business to anywhere near the degree that Mark did, they did show a few demos of ideas in development whilst also, Mark claims, expressing a certain level of concern about a lack of really compelling products in their pipeline. A few days later Doug called Mark to say they had decided “not to go forward with” the acquisition, and that was that. Mark, for whom the burden of complete responsibility for Penguin and everyone who worked there was becoming heavy indeed, remembers feeling “disappointed.”

But there was nothing to be done about it and no one else to whom he was inclined to entrust Penguin, so he went back to tweaking and refining the Spy’s Adventures series that was increasingly starting to look like the best thing Penguin had going as the air rushed out of the bookware bubble and the Apple II, The Graphics Magician’s bread-and-butter platform, got longer in the tooth. Mark and his colleagues made it possible to play the Spy’s Adventures solo or multi-player, the latter in either a competitive or a unique cooperative mode. They produced guides and supplemental software for teachers looking to integrate the games into a curriculum. And they tested, tested, tested. They took their time, wanting to make sure the series was perfect. If they could get the first three games out by the end of the year, it should be more than early enough, given that schools traditionally budgeted and purchased for the next school year in the spring.

Then came the Summer Consumer Electronics Show in June. “Have you seen the Brøderbund booth?” a colleague asked Mark. No. “Well, you need to.”

Brøderbund was showing a demo of Where in the World is Carmen Sandiego?, a game you probably already thought of some time ago, when I first described Penguin’s take on the educational geographical adventure game. Livid, Mark tracked Doug down and confronted him right there on the show floor. The latter refused to engage in any discussion, other than to say that he “knew nothing” about Carmen Sandiego at the time of the January meeting and that he always did his best to exchange information with others to avoid this sort of thing. Their friendship effectively ended right there. Mark:

My contacts with Doug after that were short. He either did not reply, or replied tersely. He was a lawyer. I don’t know if he felt he had to watch his words, thus the fewer the better?

At this point we want to be just a little bit careful. There was a period of time when Mark believed the most sensationalistic and dastardly interpretation of these events to likely be true: that Brøderbund blatantly stole his idea for a geographical educational adventure and rushed it out as Carmen Sandiego before Penguin could get the Spy’s Adventures out. Today he no longer believes that interpretation to be terribly likely. Nor do I. To believe it requires one to believe in a thirty-year conspiracy of silence amongst the considerable number of people who were involved in the creation of Carmen Sandiego, not all of whom proved to be all that committed to the Carlstons or Brøderbund in even the short term; Dane Bigham, for instance, architect and programmer of Carmen Sandiego‘s cross-platform game engine, left the company as something less than a happy camper just months after the game’s release when he was informed that he would have to start taking a fixed salary rather than royalties. It’s also difficult to believe that Brøderbund could have come up with the character of Carmen herself and the idea of the included almanac, neither of which were in Penguin’s version, and managed to design and program a demo featuring it all in the bare handful of months between January and June. Nor does it seem at all in keeping with Doug Carlston’s apparently well-earned reputation as one of the nicest, fairest people in software.

The real significance of this incident for Mark and for Penguin is more subtle, but perhaps all the more poignant for it. When he told the story to me in detail for the first time, I replied with a ham-handed array of practical questions. Did you not have Brøderbund sign some sort of NDA or other agreement before you told them pretty much everything there was to know about the state of your business? Once you gifted him with the information that you had such a similar project, what was Doug to do, potentially torpedo his own project by telling you? When you approached him with aggressive questions implying he had stolen your idea, can you really blame him so much for doing the lawyerly thing, limiting his liability by saying as little as possible and keeping away from you as much as possible from then on? Wasn’t Doug, in addition to being a nice guy, also a businessman with the livelihood of many others (including most of his own family) depending on the continued existence of his company, and doesn’t that sometimes have to trump friendship?

Mark replied that I “don’t really understand how magical those early years were, and how this was such a dramatic departure.” Doug should have told him that Brøderbund had something so similar in development, and they would somehow have worked something out. Even the mild bit of dishonesty that it’s quite hard to absolve Doug of — that he somehow hadn’t known that Carmen Sandiego was in development at the time of the January 1985 meeting, a claim he himself has refuted in many interviews since — seemed totally out of character for the straight shooter Mark thought he knew. Clearly Doug found himself on the horns of a difficult and ethically ambiguous dilemma. You can judge his behavior for yourself. For Mark, though, these events served as a canary in a coalmine telling him that the days of the software brotherhood were gone and the industry that had replaced it may not be someplace he wanted to be. If this tormented business could bring a nice guy like Doug to behave this way, what might it force Mark himself into doing? If Doug’s behavior represented simply “good business,” did he really want to be in business?

Penguin did publish the first three Spy’s Adventures games as planned, but by then Carmen Sandiego had already been out for a couple of months. Mark continues to believe that the Penguin games are better than their Brøderbund counterparts, noting that they contain all of the information the player needs to play them in-game rather than relying on an outside resource. The multiplayer possibilities, he notes correctly, also give them a whole additional dimension. Personally, I acknowledge the latter point in particular as well taken, but remember that big old almanac as a huge part of Carmen Sandiego‘s appeal, most definitely a feature rather than a bug. Whatever, there just wasn’t room for two lines of educational geographic adventure games, and Brøderbund cornered the space for themselves by releasing first and doing a masterful job of promotion; as Mark himself wryly acknowledges, just the names Where in the World is Carmen Sandiego? and The Spy’s Adventures in North America tell you everything you need to know about the relative promotional flairs of the two companies. The Spy made it to North America, South America, and Europe, but no further, while Carmen eventually conquered time and space and even the PBS airwaves.

Whilst Mark was still reeling from seeing Carmen Sandiego at that CES show, there came another disillusioning moment: he was forced to change the ground of Penguin’s very identity, its name. A couple of years before, when the world of book publishing was beginning to eye that of software publishing with greedy eyes, the Penguin Group had legally objected to the Penguin Software trademark. His lawyers informed Mark that he had a reasonable chance of winning on the merits of the case — his company had been in software first, after all — but the other Penguin had the money and legal resources to make any victory so expensive and time-consuming that it couldn’t help but bury his little company — which was, one suspects, exactly what the Penguin Group, hundreds of times bigger than Penguin Software, was relying on. Mark played for time by dragging out the discovery process and subsequent negotiations as long as he possibly could. But at last as 1985 drew to a close Penguin Software began the difficult process of educating the public about their new identity as “Polarware,” a name that never quite fit and always rankled. A final agreement severing Polarware from the old Penguin name forever was signed in 1986. The bullying tactics of the Penguin Group are doubly dispiriting in light of the imprint’s noble history as the first to bring affordable paperback editions of great literature to the masses. (And, astonishingly, the tactics were still continuing a decade after Polarware closed up shop; see the threatening letter Mark has published on his own site, which leaves one thinking that surely their lawyers must have something better to be doing than policing collections of long-obsolete software for long-obsolete computers.)

With the Spy’s Adventures a bust, the newly minted Polarware must rely entirely upon the other two legs of that strategic triangle, the graphics software and the Comprehend line of adventure games. They released two more Comprehend games in 1986 to join Antonio Antiochia’s Comprehend-revamped Transylvania and its sequel of the previous year. Both 1986 games were also remakes, signs of a maturing industry now able to mine the “classics” of its own past.

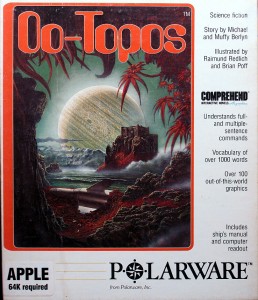

One of them we’ve met before on this blog: Oo-Topos, one of the two science-fiction adventures Mike Berlyn had written during his early days with Sentient Software. Mark had known Mike for some years already by 1986, having first met him when Mike was working on an arcade game that Sentient would eventually release as Congo and called Penguin with some questions about how to use The Graphics Magician. As the Comprehend line was getting underway, Mark proposed to Mike, who was still at Infocom at the time, that Penguin/Polarware be allowed to remake Oo-Topos using the Comprehend engine. It sounded fine to Mike, but for two problems: his position at Infocom made it difficult for him to directly involve himself with the remake; and the actual rights to the game resided not with Mike but with his erstwhile partner at Sentient, Alan Garber, from whom he had split on less than amicable terms. Mark was able to work out a deal with Garber instead. Mike received no royalties, but gave his blessing to a remake which smoothed away most of the rough edges of the original and of course added graphics. The result was a very enjoyable adventure game.

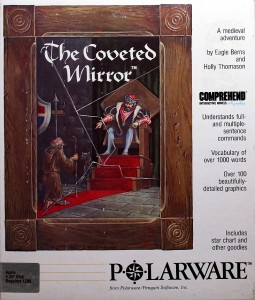

The other game, a charming little fantasy called The Coveted Mirror, was of more recent vintage. The erstwhile Penguin Software had published the original, written and illustrated by freelance illustrator Holly Thomason and programmed by a Stanford systems programmer named Eagle Berns, in 1983. (Berns would go on to quite a career inside Silicon Valley, working most notably for Apple and Oracle.) The new version removed the several surprisingly good arcade-action sequences from the original, but added some additional locations and puzzles in compensation.

The Comprehend adventures are not innovative in the least, and indeed were already feeling like throwbacks in their own time, the last holdouts from the old Hi-Res Adventure approach to adventuring that Sierra had birthed with Mystery House and The Wizard and the Princess and long since abandoned along with most of the rest of the industry. For all that, though, I have a huge soft spot for the line. They are, mark you, full of the sort of old-school attributes that will drive most of you crazy: mazes, inventory limits, limited light sources and other sorts of timers, vital information hidden in the graphics, parsers that don’t understand simple constructions like “DROP ALL.” Yet there’s a certain sense of design craft to them that’s lacking in so many of their competitors, and most of all a welcome sense that their authors want you to solve them, want you to have fun with them. Excluding only a few misbegotten riddles in The Crimson Crown, there are no stupid guess-the-word parser puzzles, no cheap tricks meant to send you scurrying with cash-in-hand for the hint book. If you can accept the different standards of a different era, they’re just about the most consistently playable line of parser-driven adventures of the 1980s, excepting only Infocom. Others may have reached further and occasionally soared higher, but their literary aspirations much more frequently only led them to create games that didn’t really work that well as, well, games. Despite their branding as “Interactive Novels,” a mode of phraseology very much in vogue at the time of their conception, the Comprehend titles are content to just be fun text adventures, an impressively nonlinear web of locations and puzzles to explore and solve in the service of just enough plot to get you started and provide an ending.

In addition to five released Comprehend games, Polarware signed contracts for and storyboarded two licensed games that would never get made, one to be based on the Frank and Ernest newspaper comic strip, the other on Jimmy Buffett’s anthem “Margaritaville.” The latter makes a particularly interesting story, one that once again begins with Mike Berlyn.

One year Mark and Mike had found themselves on the same flight from Chicago to Las Vegas for the Winter CES, and arranged to sit together. The conversation came around to music, whereupon Mark mentioned his love for Jimmy Buffett. Long before the Parrothead circus began, Mark had seen him as a struggling singer/songwriter who passed through the University of Illinois student union to sing his poignant early songs of alcohol-addled losers and dreamers adrift on the Florida Keys. Mike mentioned that he had actually lived quite close to Buffett during his tenure in Aspen, Colorado, with Sentient, and that he believed Buffett still had a house there. Knowing only that Buffett lived (according to Mike) in the “Red Mountain subdivision” of Aspen, on a lark Mark sent a letter off to just that: “Jimmy Buffett, Red Mountain subdivision, Aspen, Colorado.” Four months later one of his employees came to him to tell him that “there’s this guy who says he’s Jimmy Buffett on the phone for you.” There were plans in the works to make a movie out of “Margaritaville,” and it seems Buffett and his associates thought a computer game might make a nice companion (even given that it was somewhat, um, debatable how much of a cross-section there really was between computer gamers and Jimmy Buffett fans). But the movie plans fell through in the end, and neither movie nor game got made.

Penguin/Polarware had managed to stay afloat and even modestly profitable through 1985, but as the mass-market distributors gained more and more power they were increasingly able to impose their will on a small publisher, stretching the time between the shipment of an order and receipt of payment to thirty, sixty, ninety days or longer. Distributors came to dictate terms to such an extent that Polarware might ship them a $30,000 order only to have the distributor announce a few months later that they’d only sold $12,000 of it and thus would only pay for that, while, what with sales having been so slow, they wouldn’t even bother trying to move the rest — but no, they wouldn’t be paying for or returning the leftovers either. Bigger players might impose their own will on the distributors or set up their own distribution systems (as Electronic Arts did from the beginning), but there was very little that Polarware could do. While they did try forming a distributor, which they called SoftRack, to handle their own wares and those of a few other small publishers, it never penetrated much beyond some small independent retailers in the Midwest. For the rest, they must rely upon the established big boys, many of whom lived fast and close to the edge. At the beginning of 1986 what Mark had been dreading finally happened: a few distributors went bankrupt while owing Polarware a lot of money. With accounts suddenly deeply in the red, he was forced to embark on the heartbreaking process of laying off lots of employees he had long since come to regard as friends.

The frantic down-sizing and cost-cutting was enough to let Polarware weather this crisis, but Mark had decided by the end of the year that he’d had enough. The future looked decidedly uncertain. The Spy’s Adventures were a bust, while the Comprehend games had proved only modestly successful. And now the graphics utilities, always the company’s financial bedrock, also faced a doubtful (at best) future. The 8-bit platforms they ran on were now aged, with the press beginning to speculate on how much longer they could possibly remain viable, and Polarware had nothing in the works for and no real expertise with the next generation of 16-bit graphical powerhouses. The Comprehend line also desperately needed a facelift for the new machines, one that the down-sized Polarware wasn’t really in a position to provide. Meanwhile the stress of running Polarware was keeping Mark up at night and starting to affect his health. It was time to quit. Mark walked away, selling Polarware to a group of employees who still thought they could make a go of it. They would manage to release one more Comprehend game, an original with the awkward title of Talisman: Challenging the Sands of Time, in 1987 before accepting the inevitable and selling out to Merit Software.

For his part, Mark pursued a growing fascination with the then-new computerized music-making technology of MIDI. That led to an early MIDI software package, MIDI OnStage, and combined with the Jimmy Buffett connection he’d established at Polarware took him to Key West to help set up Buffett’s Shrimpboat Sound recording studio; his work rated a mention in the liner notes of the first album Buffett recorded there, Hot Water. Since then Mark has filled his time with quite a variety of activities: setting up another studio for Dan Fogelberg; playing steel drums in a band; developing the mapping technology for early travel-planning CD-ROMs; teaching one of the first online courses ever offered and developing much of the technology that allowed him to do so; developing early web-forum software; teaching programming for twenty years at Elgin Community College. He’s now retired from that last gig, but remains busy and industrious as ever; when I first contacted him to ask him to help me tell the Penguin/Polarware story, I was surprised to find him volunteering as a technology architect for Barack Obama’s 2012 reelection campaign. Mark escaped the chaos with little apparent psychic damage, something not necessarily true of all of his contemporaries.

When I put Penguin behind me, I felt like I’d already had a lifetime of experiences, much more than most people could hope for, imagine, or dream. And I kind of treated what came after as another lifetime. I joke, but only half so, about how “in a past life…’ I did this and that, when talking about things like Penguin Software. But it really does kind of feel like that, and that probably helped keep me sane in living another, more normal life.

(You can download the Comprehend versions of Oo-Topos and The Coveted Mirror for the Apple II, including manuals and all the other goodies, from here if you like.

For another and presumably final time, my thanks to Mark Pelczarski. His memories, which he shared with me in careful detail even though this period of Penguin/Polarware’s history is not his favorite to remember, were just about all I needed to write this article.)

matt w

September 12, 2014 at 11:33 am

Thanks for this look into this corner of history! I’m glad things worked out for Mark in his life in the end. Speaking of which, a copyediting thing: In “Unlike some other survivors of those crazy early days of consumer software, Mark escaped the chaos with little apparent psychic damage, something not necessarily true of all of his contemporaries,” it seems like the first and last clauses basically repeat each other.

On the trademark dispute, it seems to me that that’s how a lot of intellectual property law works. You may have an excellent claim for fair use or parody or something (this is from copyright rather than trademark law, but the same idea applies), but if your opponent has deep pockets and you don’t then it’s basically impossible to fight once you receive that cease & desist letter. (See this description of a dispute with Wizards of the Coast, though WotC may have had a slightly stronger claim there than is often the case.)

Jimmy Maher

September 12, 2014 at 12:01 pm

Thanks! The link you provided seems to parallel the Penguin story almost exactly.

Andrew Plotkin

September 12, 2014 at 5:13 pm

Coincidentally, I just ran into this scanned article from 1985: http://gamepreservation.tumblr.com/post/96109922514/if-yr-cmptr-cn-rd-this-from-the-august-1985

Competition in parser technology between the IF companies. Has quotes from Pelczarski, Seth Godin, Brian Fargo, John Williams, Marc Blank, etc.

Obviously there never was a generation of IF that took real advantage of a “next-generation” parser, and modern IF tools have taken the conservative path. I should write up something about that.

Healy

September 12, 2014 at 11:04 pm

Please do! I’d like to read your thoughts on it.

Jimmy Maher

September 13, 2014 at 8:23 am

The idea of a “next-generation parser” has always proved to be something of a dead end because nobody has ever really figured out what such a beast should be. Marc Blank and Mike Berlyn put considerable work into a parser that could process adverbs and to at least some degree deal with affect as well as effect during 1983/84, but the work was ultimately abandoned as impractical. Later, circa 1987/1988, Infocom completely rewrote their parser for the version 6 graphical games (which were developed on Sun workstations rather than the famous old DEC). They advertised this as their “next-generation” parser, but most folks couldn’t really see much of a difference.

The “next-generation” parsers of companies like Telarium and Synapse quickly degraded into simple pattern/word matchers that tried to guess the meaning of more complex or idiosyncratic inputs. Subsequent experience has taught us that that’s a pretty horrible idea, but during the 1980s virtually everyone other than Infocom was doing it. Infocom never succumbed to the temptation, which is one among many reasons why their games stand up so much better than anyone else’s today. (Even the Comprehend games, which I find unusually playable, indulged in a bit of this, although they were nowhere near as prone to non sequiturs as most of the competitors.)

One big limitation of this era, as Mark was at pains to emphasize to me when we discussed these topics, was the miniscule memories and processing powers available on the 8-bit machines for which these games were targeted. If you simply don’t have enough memory to pack in all the words you want to be able to understand, it’s awfully tempting to engage in a little guesswork instead of just throwing up lots more error messages.

Modern computers obviously aren’t subject to the same restrictions. It would indeed be interesting to see what a “next-generation” parser might look like — but it would also, I suspect, require development resources that just aren’t available to a hobbyist community.

David Cornelson

September 12, 2014 at 8:04 pm

Great article Jimmy. Being an entrepreneur, I’m always concerned about someone intentionally or unintentionally disrupting my vision and I can’t imagine how painful that moment at CES was for both Mark and Doug. In the end, you have to work with the mindset that if your vision is meant to win, it will and if not, it won’t. Success always has a bit of luck and talent mix. It’s the luck part that drives entrepreneurs mad.

David Lubar

September 13, 2014 at 2:22 pm

Great article. Just one minor point — I wasn’t with Mark when he met Chris. I don’t think I was ever at Doug Carlston’s house. (I didn’t move from NJ to Saramento until 1982.) I do remember taking a trip from Sacramento to visit Brodebrund. I went there with Tim Wilson. (We’d worked together at Sirius.) They’d just gotten a Famicon in the office, if that helps date things. But it’s wonderful to read such a detailed history of some of Mark’s achievements. He’s an amazing guy.

Mark Pelczarski

September 13, 2014 at 5:33 pm

You’re right David, but I interpreted that metaphorically. What was a two-person project in writing Graphics Magician became a three-way coast-to-coast project with you in NJ, me in Illinois, and Chris in California (and our version of the Internet was sending 5-1/4″ floppies in the mail). While we’re at it though, I should clear up another part of the wording: David Lubar is the person responsible for most of the animation routines in GM, particularly all the gut-level assembly language stuff. What Chris brought to the project was the overall path generation concept that tied it all together, which I programmed around David’s machine language routines. Chris was using that technique to write his Space Quarks game and later implemented it in The Arcade Machine, but David’s programming was the heart of the animation portion of Graphics Magician.

While I’m here, I’d like to thank Jimmy Maher publicly for all his remarkable work and research in bringing this era back to life. I thought I knew a lot about it from inside my little Penguin bubble, but it’s fascinating reading about all the other perspectives, issues, ideas, and growing pains of the time. While others have addressed the era mostly from the perspective of one of those individual bubbles, Jimmy’s collection of articles has been one of the most thorough and enjoyable accounts of that time that I’ve seen. Thanks Jimmy! Keep up the great work.

ZUrlocker

September 16, 2014 at 3:53 am

Mark, I loved those old Penguin games. Spy’s Demise in particular was a lot of fun on the Apple ][. Thank you for all you did for the gaming industry.

Mark Pelczarski

September 13, 2014 at 5:38 pm

I’ll add this: If you’re not familiar with David Lubar and if you know any young adult readers, look him up in your library or bookstore, or at davidlubar.com!

Carl

September 16, 2014 at 5:29 pm

Just a small point: Eagle Burns was a systems programmer at Stanford, not a Professor.

Jimmy Maher

September 16, 2014 at 6:41 pm

Thanks!

Carl

September 17, 2014 at 12:05 am

By the way, saw your Amiga book at the Computer History Museum on Sunday. I’d have bought it if I didn’t already have it!

RVP

September 24, 2014 at 9:54 pm

Nice article; a minor typo in the title though: Magnificient should be Magnificent.

Jimmy Maher

September 25, 2014 at 5:34 am

Woops! Thanks!

James

January 29, 2015 at 5:36 pm

Typo roundup:

“an artist named Gini Shimabukuro approached him with a big collection of clip-art images. … Mark sent Gina over to the Brøderbund booth, and her art eventually became a big part of The Print Shop’s finished look”

You seem to switch from Gini to Gina and I’m not 100% sure which you were going for.

” The Graphics Magician’s bread-and-butter platform, got older in the tooth. ”

I think the colloquialism or idiom is actually ‘longer in the tooth’

http://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/long_in_the_tooth

“Buffett’s Shrimpboat Sound recording studio; his worked rated a mention in the liner notes of the first album Buffett recorded there”

work, not worked :)

Jimmy Maher

January 30, 2015 at 7:25 am

Thanks!

Jason Kankiewicz

July 11, 2017 at 8:36 pm

“would soon became famous” -> “would soon become famous”?

“play the Spy’s Adventures single-” -> “play the Spy’s Adventures solo”?

Jimmy Maher

July 13, 2017 at 11:47 am

Thanks!

Ben

March 20, 2022 at 4:19 pm

him to to tell -> him to tell

Jimmy Maher

March 22, 2022 at 8:28 am

Thanks!