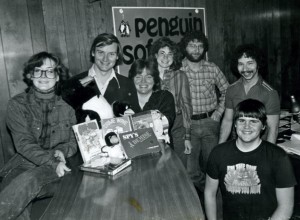

Inside Penguin Software, circa early 1983. From left: Mary Beth Pelczarski, Mark and Trish Glenn, Cheryl and Mark Pelczarski, Ron Schmitt, and (at right front) Larry Weber.

It’s been quite some time since we’ve checked in with Penguin Software and its founder Mark Pelczarski, so let’s be about that today. The Penguin story is not only interesting in its own right but also a good illustration of what it was like for a small publisher trying to navigate the home-computer boom and bust.

On the heels of the considerable commercial success of Transylvania in 1982, Penguin was naturally eager to continue to work the games market. An old associate from Mark’s days at SoftSide magazine, Dave Albert, essentially took over that side of the company. Over the next couple of years he shepherded to completion a mixed bag of titles from outside contributors, including a number of action games, three more “hi-res adventures” in the mold of Transylvania, and even a couple of RPGs, one crazily original and one more typical of its genre. Most earned back their investment but were not major moneyspinners; only one of the action games, Spy’s Demise, and one of the adventures, The Quest, managed anything close to the numbers that Transylvania moved.

Penguin’s core product remained The Graphics Magician. Now with ports to the Commodore 64, Atari 8-bits, IBM PC and PCjr, and eventually even the new Apple Macintosh as well as the Apple II original, it was the closest thing the games industry had to a standard graphics tool in those wild early days, to be superseded only in the second half of the decade by Electronic Arts’s Deluxe Paint line. For a considerable period of time a considerable percentage of the games on the market employed it, as did countless amateur artists and programmers. Its ubiquity could bring its author into some surprising company.

There was, for instance, a period when Penguin kept getting calls from a kid named Conan O’Brien, editor of the Harvard Lampoon. The name was so crazy that it became a regular part of Penguin’s intra-office schtick: “Conan called again!” someone would shout almost every day. Mark finally agreed to come by Harvard on a business trip. Conan showed him around the campus, and also showed him a basketball “simulation” he and his buddies had developed with the aid of The Graphics Magician. In it the Boston Celtics took on a classical ballet troupe, to hilarious effect. Electronic Arts’s One-on-One, the spiritual father of the modern EA Sports line which pits Julius Erving against Larry Bird, was one of the most popular games in the country at the time; thus Conan’s little creation, whatever else it was, also qualified as satire of a sort. Conan claimed to have gotten a contract with EA to publish the game, but the project never made it to fruition. Had it done so, we might be talking today about Conan O’Brien the game developer rather than Conan O’Brien the talk-show host. (It’s also possible, of course, that “I have a contract” in this context meant “I’ve signed an agreement to quit publishing derivative works of EA intellectual property in exchange for not getting sued.”) For his part, Mark forgot about it — until he opened Newsweek a decade later to read that Conan O’Brien was replacing David Letterman in NBC’s late-night time slot.

The fury and frenzy of the home-computer boom was soon swirling around Penguin, bringing with it dramatic changes in the way that software was sold and marketed. Mark, a sober and grounded sort, wisely steered Penguin clear of the worst excesses of many of their competitors. Penguin didn’t flood the market with cheap cartridge-based titles (“it really didn’t match what we felt we were best at”); didn’t hire a big-name celebrity spokesperson; didn’t let the venture capitalists take control; didn’t mortgage their future via dangerous bank loans. Yet, as wise as those choices would soon prove to be, it became ever harder for a small company to get noticed amidst the glut of product being pumped into stores by 1984.

That year, concerned about the changes in the industry and increasingly nervous about relying so heavily for their sustenance upon a single product, Penguin formulated a three-pronged strategy for the future. They would devote about one third of their resources to continuing to support and improve The Graphics Magician. One third would go to a new line of edutainment software of which we’ll have occasion to hear more in a future article. And one third would go for a renewed and much more focused push into games. With Dave Albert about to leave Penguin to join Origin Systems, it seemed a good time for a change in strategy in this area. (Albert, incidentally, took with him to Origin Greg Malone and his oriental RPG Moebius amongst other projects in progress).

Henceforth Penguin would concentrate on adventure games, the genre which had been most successful for them and for which they were best known. Their previous adventures had all been essentially one-offs submitted by outside authors and programmed in whatever combination of assembly language and BASIC happened to seem most handy. All had originated on the Apple II, and porting them to the other popular platforms of the day had been tedious and expensive if it happened at all. Nor did their home-grown parsers acquit themselves all that well in this the heyday of Infocom’s reign. The answer to all these problems was to be Comprehend, a cross-platform adventure-game engine that should let Penguin put out more sophisticated adventures more quickly and on more platforms, and all in a consistent house style that players could come to know and intuitively understand like that of Infocom. In a collaboration he describes today as still “one of the most interesting and fun I’ve had writing and programming,” Mark designed Comprehend from whole cloth in front of a whiteboard over the summer of 1984 with a student from the nearby Northern Illinois University, Jeffrey Jay. They paid particular attention to the parser, which they put through a series of challenges posed to them by the folks at Infocom — pronoun handling, accurate handling of compound sentences, etc. — that most rival parsers definitively failed. What they ended up with didn’t come close to matching that magnificent Infocom parser, but it was several steps above the likes of the Telarium model.

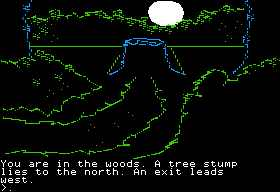

Text adventures with graphics can be divided into two categories. First there are those, like the Telarium games, for which the graphics are static and ancillary to the text, there only for atmosphere — like, say, the occasional illustrations in an original-edition Dickens novel. Then there are those — counterintuitively, this is the older category, pioneered by Sierra’s original Hi-Res Adventure line — which make the graphics an integral part of the experience, using them to convey essential information about the game world that isn’t in the (generally much sparser) text and varying them with changes in its state: drawing dropped inventory objects and other characters that happen to be present into the scene, etc. This style had rather fallen out of fashion by 1984 as publishers rushed to jump onto the bookware bandwagon that posited adventure games as essentially literary experiences. Comprehend, however, bucked the trend by hewing to the older style that Sierra themselves had abandoned with the advent of AGI and King’s Quest. This could make Comprehend seem like a bit of a throwback even in its heyday. Still, the graphics possibilities were, as one might expect from “The Graphics People,” considerable, with the system even capable of some spot animation and other flourishes. The system also ran blazingly fast in comparison to the likes of Telarium’s SAL engine. Comprehend was, in short, a perfectly serviceable old-school adventure engine if hardly a technological game-changer. Now Penguin just needed some Comprehend games.

Antonio Antiochia, the teenage author of Transylvania, had been enjoying the fruits of that game’s success in the form of the royalty checks, insanely large by a high-school kid’s standard, that he found in his mailbox each month. Mark duly suggested to his young software star that he save his money for university, but Antonio did exactly what most of us would have done in his place: went out and bought a shiny new Mazda RX-7, which may or may not have contributed to his getting his “first bona fide girlfriend” late in his senior year. With such distractions on offer, it took Antonio some time to buckle down again to adventure writing. When he did, he decided he’d like to make a sequel to Transylvania, something that Penguin, in light of the success of the first game, was hardly likely to discourage. Antonio started drafting his game using a BASIC-based framework that another of Penguin’s outside authors, The Quest and Ring Quest author Dallas Snell, had developed, once again doing not only all the writing and programming but also drawing all of the pictures himself. (This incomplete early version leaked into pirating circles through the cracking group the Corsairs, and can still be found in some Apple II software archives today.) Later, when Comprehend was ready, Antonio dutifully learned its nuances and ported his work to the new system. After completing the sequel, dubbed The Crimson Crown, he returned to the original, crafting a new version for Comprehend with more text, locations, and puzzles. Together these became the first two Comprehend releases from Penguin in the fall of 1985. The Apple II versions of both games were reworked and re-released yet again early the following year, to use the “double-hi-res” graphics mode available on certain IIe setups and all models of the IIc. This welcome hardware enhancement let Penguin mostly if not entirely eliminate the color distortions that normally plagued Apple II graphics.

The Crimson Crown is a much bigger game than the original Transylvania. In fact, it’s really two adventure games, one on each side of its disk. Stealing a trick that was quite common in the British software market where sharply limited cassette-based machines were still the norm, The Crimson Crown arranges to funnel you through a bottleneck at its mid-point in which you lose your inventory and are moved to an entirely new piece of geography. In other words, everyone who gets this far is forced into the same state before continuing the game — or, I should say, before beginning the second game that occupies that second disk side.

Following, like just about everyone else in the industry, the lead of Infocom, Penguin upped their packaging game considerably for the Comprehend line. The Crimson Crown shipped with not only an instruction manual but a separate journal setting the stage, a sealed letter to be opened at a certain point in the game, a map of Wallachia and Moldavia, and even a poster to hang on your wall. The Transylvania connection was oddly minimized, relegated to a subheading — “Further Adventures in Transylvania” — below the much larger Crimson Crown title. Mark Pelczarski notes today that such decisions point to a certain ongoing naivete at Penguin even in an increasingly cutthroat market, a determination to emphasize “fun and art” over “the monetary aspect.”

You play the hero of the first game, rescuer of the Princess Sabrina. The vampire who abducted her has turned out to be not as dead as everyone — you most of all — thought. (Well, I suppose he is technically dead, but you get the idea…) He’s murdered the king of your land of Wallachia and stolen the Crimson Crown that gives the king supernatural powers. And so it’s back into action, accompanied this time not only by Sabrina, who has gotten sick of playing the damsel in distress and scored one for female empowerment by learning the art of sorcery, but also her brother, the king-to-be Erik, more the earnest sword-wielding type. You’ll guide this three-headed monster through the entirety of the adventure, mostly doing things yourself but occasionally needing to call upon Sabrina or Erik’s prowess by giving them instructions.

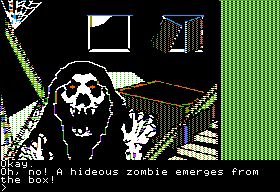

The sequel has most of the same qualities going for it that made the original Transylvania such an old-school favorite of mine. Some of the delicious B-horror-movie atmosphere is absent, with the game this time having a bit more of a conventional fantasy feel; in addition to the vampire, there’s a zombie, a troll, a centaur, and a dragon to contend with this time instead of the werewolf of the original, and much of the second game takes place in what amounts to a typical fantasy dungeon rather than the Gothic landscape of the original. Indeed, Antonio seems to have been playing quite some Dungeons and Dragons at this point in his life; you and your companions are repeatedly referred to as “the party.” And the sequel is in general a bit trickier to solve. But, aside from one horrible choice which we’ll get to momentarily, The Crimson Crown is quite fair and even progressive in its design sensibilities, being notably free of mazes, uselessly empty geography, sudden random deaths, and most other things modern adventurers have come to hate. It even has a handy carry-all to make the inventory limit less onerous, and a “sage” who pops up from time to time to offer little nudges for some of the puzzles and strategic guidance for the game as a whole. Like its predecessor, it smartly works within its technological limitations. The parser, for instance, while not quite state of the art, doesn’t have to be because the game never tries to push it to places it isn’t capable of going — a marked contrast with Telarium, whose games made a habit of being too big for their parser’s britches. Despite these signs of maturity, The Crimson Crown retains its predecessor’s giddy teenage enthusiasm, which remains a big part of its charm. Solving this one is both possible and very, very enjoyable.

Except, that is, for the riddles. The Crimson Crown resoundingly fails to put its best foot forward by hitting you almost at the very beginning with four riddles. We’re talking absurdly abstract stuff like this:

I am, I’m not. I visit young and old,

Some I make timid and some I make bold,

Unwise is the one who pokes fun at me.

Beware, for I am a shadow of thee.

The answer to that one is “dream”, and if you solved it you’d best get to playing The Crimson Crown immediately because three more just like it await your powers. As for the rest of you, I actually recommend that you play as well, but don’t spare a moment of thought to the riddles. Here are the other answers: “windmill,” “fear,” and “cloud.” You can download The Crimson Crown in its double-hi-res Apple II incarnation from this very site if you like.

We’ll continue the story of Penguin and of Comprehend in later articles, but next we’re going to turn away from text adventures for a while to look at developments in other genres over this period in North America.

(My thanks to Mark Pelczarski and Antonio Antiochia, whose memories informed this article.)