Technological futurists and the people who love them have been talking for some time now about something called the Singularity, that moment in the (near?) future when computing technology will reach some critical mass and change everything forever in ways we can hardly begin to imagine. I’m not so interested in discussing the merits of the idea here, but I do want to say that singularities can take many forms, and to note that the sort of singularities one sees are perhaps more emblematic of one’s own personal hobby horses than some might like to admit. In that spirit, I’d like to propose a singularity of my own, albeit one recently passed rather than oncoming. It landed right about the middle of the 1960s.

To see what I’m talking about, watch a movie or listen to a hit song from 1960 followed by one from 1970. While it may be extreme and rather narcisstic and certainly horridly Western-centric to divide all recent history into pre-1960s and post-1960s, it’s nevertheless hard for me to come up with another instant when everything changed so completely. Films and songs are of course only signifiers of the deeper changes in the culture: changes in gender roles and responsibilities, in race relations, in attitudes toward war and peace and government and the rights and responsibilities of the citizen. The 1960s changed the way people talked, the way they dressed, they way they thought in a way far more profound than the mere vicissitudes of fashion. Perhaps most of all, they changed what is still for so many the most uncomfortable of uncomfortable subjects, sex, forever. We’re still dealing with the fallout every day: in the United States, at least, your decision of which party to vote for still has a great deal to do with whether you think all of these changes were in general a good or a bad thing.

Even written science fiction, that literary ghetto which had hitherto marched along blissfully ignoring and being ignored by changes in the larger world of arts and letters, wasn’t insulated from these winds of change. A New Wave of writers poured into — the old guard might, and sometimes did, say “invaded” — the stolid old halls that the pulps had built. These new writers were very different from the old holy trinity of Asimov, Clarke, and Heinlein. They replaced an absolute faith in objectivity and rationalism with a tolerance for ambiguity and an honest curiosity about spirituality, particularly (this being the 1960s) of the Eastern variety. They replaced adventures in outer space with explorations (this again being the 1960s, when psychedelics were everywhere) of inner space. They replaced workmanlike (not to say clunky) prose with literary flights of fancy and experimental structures showing the influence of folks like James Joyce and William S. Burroughs; a surprising number of the New Wave stars were poets in addition to short-story writers or novelists, for God’s sake. They replaced characters that served primarily as grist for the mill of Plot and Idea with real, three-dimensional humans whose subjective experiences were the point of the works in which they featured. American science fiction, like seemingly every other institution in the country, went to war with itself for a time, with John W. Campbell opining on behalf of the Old Guard in the pages of Analog that the Kent State protestors had gotten what they deserved while Michael Moorcock preached anarchism and feminism from his soapbox as editor of New Worlds.

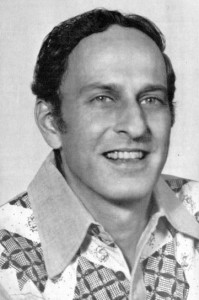

One of the biggest stars of the New Wave is our real subject for today: the man with the perfect science-fiction writer’s name of Roger Zelazny. He burst onto the scene in the mid-1960s with a series of dazzling short stories and a short novel, This Immortal, which took place on a post-apocalyptic Earth populated by creatures and minor gods from a sort of fever dream of Greek mythology. Then in 1967 he delivered Lord of Light, an audacious transplantation of the Hindu pantheon — if you haven’t realized it already, Zelazny was big on myth — to an interstellar milieu. The structure was as intricate as many a Modernist novel, the language gorgeous. The central character, Mahasamatman (he “called himself Sam”), reminds one in his rebellion against the rest of the pantheon of no one so much as the Satan of Paradise Lost.

Lord of Light deservedly swept science fiction’s two biggest prizes, the Hugo and the Nebula Awards, for its year. Along with a groundbreaking collection of short stories of the same year edited by Harlan Ellison and to which Zelazny also contributed, Dangerous Visions, it’s gone on to stand as perhaps the perfect exemplar of New Wave science fiction and why it mattered — this even though Zelazny himself rejected the label. There was a moment there when Roger Zelazny was accorded the honor amongst a ridiculously strong field of fellow up-and-comers of being just possibly the most promising young writer in science fiction. Lord of Light was great, but, what with Zelazny still so young, many predicted even better things from him once he matured a bit, got beyond just dazzling with the sheer high-wire virtuosity of his language and plots and began to really dig into his worlds and themes.

But somehow that never quite happened. Oh, he continued to be astonishingly prolific, releasing for instance three novels in 1969 alone. His books remained readable; Zelazny was too professional to deliver anything else. Yet, while the reputation of contemporaries like Ursula Le Guin have only soared higher in the years since the heyday of the New Wave, Zelazny gradually found himself banished to the mid-lists, just another competent and salable genre writer. Much of his later work felt kind of forgettable, at its worst even kind of facile. Maybe it was down to an unwillingness to go to the hard places. Certainly it’s hard not to feel that this writer, who throughout his career cranked out novels at the rate of one or two every year along with a steady stream of short stories, might have benefited from just slowing down a bit, from applying all of his enormous energy to a single book for a while.

On the other hand, lots of readers — more than had enjoyed the likes of Lord of Light, actually — liked the later Zelazny, liked his readable, fast-paced novels that weren’t too demanding on either their reader or their writer. Zelazny, for his part, always rejected aspirations to literature in interviews, making it clear that he considered himself simply a working writer whose first consideration must be the financial. Even Lord of Light, he eventually revealed, had some commercial calculation at its base: he made it straddle the line between science fiction and fantasy in order to maximize its readership. Lovers of Zelazny’s early work could at least console themselves that even his most pedestrian novels still showed flashes of the old brilliance. Anyway, there was still plenty of time for him to buckle down and deliver another masterpiece. Until suddenly there wasn’t: he died of colorectal cancer at age 58 in 1995.

The flash point for lovers and haters of newer Zelazny is a series of ten fantasy novels set in a world called Amber. Drawing upon Zelazny’s usual mythical archetypes as well as Platonic philosophy, the Amber series postulates a perfect shining city on a hill, Amber itself, of which all other reality — or realities; infinite alternate universes worth of them — are but imperfect shadows. As one travels outward from Amber the shadows become steadily wilder and stranger, until one arrives at last at Amber’s polar opposite, the Courts of Chaos. The elemental forces of Order and Chaos which Amber and the Courts respectively represent exist in an uneasy symbiotic state — which doesn’t prevent them from constantly trying to get the upper hand on one another. Within Amber lives a royal family of superhumans and apparent immortals. They can communicate with one another and instantly jump to one another’s locations in Amber or in shadow via a set of magical cards, the family Trumps. They can also, albeit more laboriously, visit anywhere in shadow by simply walking — or driving, or riding — there, slowly manipulating and adjusting the reality around them as they go until they arrive at just the place they were looking for. (The early books dwell for some time on the intriguing philosophical question of whether they are visiting lands that always existed in shadow or creating them in their mind’s eye; like much else, however, this question is forgotten in the later books, by which time Amber is conducting trade negotiations with lands in shadow.) Amber’s royal family, consisting of an inconveniently absent father along with nine brothers and four sisters, is riven with far more strife and suspicion than one might expect from a family supposedly representing Order. Upon their various plots rest most of the series’s most compelling plots.

The first five Amber books, later to become known as the “Corwin Cycle,” were published between 1970 and 1978. They tell of the struggles of Prince Corwin of Amber, first against his hated brother Eric for the throne and later against the forces of Chaos who threaten Amber and the very fabric of reality itself. The books proved to be very popular, by far the most popular thing Zelazny had ever written. And so he wrote another five books, the “Merlin Cycle” describing the adventures of Corwin’s son, between 1985 and 1991. Most critics will tell you that the series declines in quality almost linearly, a half-step or so at a time starting right from the second book. The first book, Nine Princes in Amber, while much more straightforwardly written and plotted than the likes of Lord of Light, breathes the old Zelazny magic as we learn about this grandly mysterious multiverse and are introduced one by one to the family of Amber and their Shakespearian intrigues and rivalries. But as the books go on with strangely little differentiation from one to another — it really does feel as if Zelazny would just write the story until he had the 225 pages that was his publisher’s ideal length, then stop for a while — it begins to feel like just a series of long, anecdotal meanderings, particularly by the time we get to the much inferior Merlin Cycle. It’s pretty clear after a certain point in the latter that he’s making it up as he goes along, and apparently forgetting in the process a good part of what he’s already written. As Amber turns from a magical perfection to a mundane place that doesn’t seem all that qualitatively different from any of the shadows, as characters reverse themselves or change personalities entirely to suit Zelazny’s newest plotting whims, as ultimately pointless digressions come to occupy entire books worth of story, the later books manage to retroactively spoil much of what came before. By the time the whole thing sputters to a halt with the most anti-climactic of endings in which Merlin does exactly what he spent the previous several books saying he didn’t want to do, much of the allure of Nine Princes in Amber has long since been ground into dust.

That, anyway, is my attitude today. I should note that 25 years ago when I first read the Amber books I thought they were magnificent, Corwin and even Merlin the most dashing and cool heroes imaginable. Now they seem as often as not like smug, smirking jerks who are nowhere near as clever as they think they are. Merlin in particular, I’ve gradually come to realize, is actually as dumb as a box of rocks; he spends most of his time like the player’s character in a videogame, being manipulated and led by the nose through his foreordained plot by other characters in the story. Still, Amber remains readable even at its worst, even when you know that none of this is really going anywhere in particular; Zelazny knew how to craft a page turner. My wife and I used my omnibus Chronicles of Amber as bedtime reading for several months. By the end we were spending a lot of time making fun of its endless, exhaustively detailed fight scenes, the occasional stabs at free-verse poetry that misfire horribly, the creepy Mary Sue quality to Corwin and Merlin (like them, we weren’t surprised to learn, Zelazny was a fencing aficionado, but presumably beautiful women didn’t all fall swooning before him the way they did for them), and the sheer stupidity of the hapless Merlin, but we did finish all ten books. I suppose that says something. Thomas M. Wagner summed up the Amber series about as charitably as one can on his reviews site: “There’s no point in pretending this is great literature any more than, say, Edgar Rice Burroughs, but it captures the quintessence of pulp escapism with just about as much purity. It’s fast-paced, gobs of fun, and requires about as many brain cells as an old Johnny Weismuller movie.” That should be good enough. Or it would be if Zelazny hadn’t proved himself capable of so much more. I’ll leave you to come down on whichever side you prefer.

Given its intriguing if not exactly rigorous fantasy milieu as well as the politicking that can make it seem like a fantastical version of Diplomacy, not to mention its considerable popularity at one time, Amber made a compelling setting for ludic narrative. In 1991, Erick Wujcik published the Amber Diceless Roleplaying Game, one of several streamlined tabletop RPG systems that appeared around that time with an emphasis on story and texture and, most of all, character interaction; this in contrast to older games like Dungeons and Dragons with their obsession with minutiae and tactical combat. Each player in the Amber Diceless Roleplaying Game takes the role of a member of the royal family. If everyone is in the proper Amber spirit, the gamemaster need not say much beyond that; the intrigues and betrayals all blossom naturally. Although it never gained the commercial prominence of fellow second-generation RPGs like White Wolf’s Vampire: The Masquerade, Amber attracted a cult of loyal players who still keep it alive today.

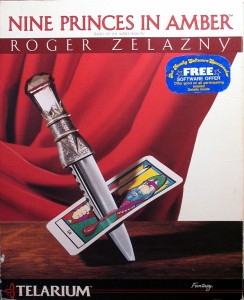

But long before The Diceless Roleplaying Game there was another ludic Amber, this one produced by Telarium for the computer. Like the simultaneously released Perry Mason game, Nine Princes in Amber appeared just as its source material was getting a boost in the form of new installments after a fallow period of some years. In the case of Amber, this material took the form of Trumps of Doom, the first volume in the Merlin Cycle and first Amber novel since the Corwin Cycle had concluded seven years before. Roger Zelazny was happy to cash Telarium’s checks, but otherwise contributed even less to the project than had Arthur C. Clarke and Ray Bradbury to their respective games. He did graciously sign his name to a suitable back-of-the-box blurb: “I’m thrilled to see my Amber books become a challenging computer adventure. For anyone interested in exploring contingent paths through my tale, the possibilities here are almost endless.” The actual game, however, is a product of the same committee approach that yielded Perry Mason.

As such things go, it’s at least a very relevant blurb. Like Perry Mason, Nine Princes in Amber is a crazily unusual and ambitious work of interactive fiction. There’s a modest slate of object-oriented puzzles to deal with as well as an elaborate and frustrating fencing simulation that has all the problems typical of randomized combat in text adventures. There’s also a graphics-based mini-game that is, unlike the horrid arcade sequences in earlier Telarium games, actually quite fun to play. Yet the main focus is once again on character interaction. The included verb list is even more far-ranging than that of Perry Mason, including some entrants that have quite possibly never featured in another work of interactive fiction before or since: verbs like “placate,” “flatter,” “mention,” “bluff,” and “stall.” The heart of the game is a series of tense encounters with your various siblings in which you’ll have the opportunity to try out those and many more.

That said, Nine Princes in Amber can at first seem underwhelming. The game seems to play out as a linear series of Reader’s Digest condensed scenes from the first two books, with most of the texture — like, inevitably, that provided by Corwin’s occasional amorous encounters — painfully absent. Do in any given scene what Corwin did in the book, and you get to continue to the next; do something else, and you get killed and see one of the “forty possible final endings” the box copy trumpets. As Jason Compton put it in a review on Lemon 64, gameplay can seem to devolve into, “All right, dammit, I know what Corwin did in the book, so how can I express it in terms the parser will understand?” In comparison to, say, Fahrenheit 451, which used its source novel as a springboard for something entirely new, this can seem depressingly unambitious, not to mention unchallenging for those who have read the books and impossible for those who haven’t.

But then, when you blunder your way at last to the end by trying to recreate the events of the novels as faithfully as possible, you get a shock: the ending you get is not a particularly good one. And so you begin to reexamine and reevaluate, and discover that Nine Princes in Amber is doing — or at least trying to do — something very audacious. It really is possible to forge your own path through the story, to end up with a set of allies and enemies radically different from those the novel’s Corwin ended up with in his own quest for the kingship of Amber. The claim of forty endings may be a stretch, but it’s possible to reach and win the climactic battle and still see the story branch at least four ways depending on your actions earlier in the game and your relationships with your siblings.

While the Corwin of the novels eventually thinks better of his own ambition to be king, this remains the goal of the Corwin of the game. The game’s universe is even more amoral than that of the novels; not for nothing do you find a copy of The Prince in your sister Flora’s study early in the story. I found I could be most successful by going into full Harry Flashman mode, lying and backstabbing and wheedling my way through events.

There are several choke points through which the narrative will always funnel, whether the player is trying to diverge from the novel or follow its plot exactly. Veterans of the books will recognize them immediately: the Pattern walk in Rebma, the time in the dungeon of Amber, the encounter with Benedict near Avalon, the final battle at the foot of Mount Kolvir. In between, the narrative can branch off in many directions. (This certain amount of linearity is necessary not least because the game is distributed on four disk sides for the Apple II and Commodore 64; the amount of disk flipping required would otherwise be horrendous.) Impressively, the reasons you arrive at the various choke points can be very different, and the relationships you’ve built or failed to build are preserved as you pass through them. In this sense of making all the pieces fit while preserving the player’s freedom, Nine Princes in Amber is one hell of an intricate piece of design.

Indeed, the game is in its way an amazing achievement. I know of no other text adventure from its era — and, come to think of it, possibly of any other — that offers this level of choice over not just the beats of the story or the order in which puzzles are solved but of the very direction of such a grand narrative. Yet it’s also often a pain to play, thanks as usual to that problematic Telarium parser. It’s nice that the game offers verbs like “placate,” but most of the time, even in conversations, most of these clever verbs do nothing; worse, it’s often hard to figure out whether any given verb is doing anything or not. Nine Princes in Amber has, in other words, all of the same problems as Perry Mason. If anything, they’re even more pronounced here.

After thinking about it a bit, I began to feel that even if its parser was much better something would still be off about the game. Many commands that do work are absurdly wide in scope and open to interpretation, sometimes causing hours or weeks to pass in the story: “walk in shadow,” “go to Brand,” “attack Amber.” Then it struck me: Nine Princes in Amber is really a choice-based narrative that’s been saddled with the wrong interface. Parsers are very good for complex but granular manipulations. Parser-based games are excellent tools for exploring geographical spaces and manipulating their contents, but not so good for exploring story spaces, for manipulating the narrative itself as does the player of Nine Princes in Amber. As Sam Kabo Ashwell wrote in his great series of articles about Choose Your Own Adventure books and other gamebooks (many of a vintage similar to this game), “CYOA is where you go when you want to prioritise free-flowing, bigger-scale narrative over deep or difficult interaction.” These are indeed the priorities of Nine Princes in Amber. The parser in this context only obfuscates what should be a delightful garden of forking paths. It leaves you constantly poking at unrewarding blind alleys that don’t work simply because that’s not one of the ways the plot is allowed to branch right now.

But imagine Nine Princes in Amber as a hypertext narrative with some limited state tracking and it all falls into place. One could create a node diagram like those Ashwell created for his articles if one was willing to spend enough time plumbing the game’s depths. This isn’t the first time I’ve observed such a disconnect between interface and content; I once went so far as to re-implement one of Robert Lafore’s pioneering experiments in ludic narrative as a choice-based game to prove a similar point. I won’t do the same here, although it is tempting; copyright concerns as well as the vastly greater complexity of the Telarium game prevent me. You’ll have to accept my word that this game would work perfectly well in any of the several viable modern hypertext-narrative engines.

So, chalk up Nine Princes in Amber as — stop me if you’ve heard this before — one more noble Telarium experiment that doesn’t really work as a playable game. Still, like Perry Mason, it’s worth some of your time just to marvel at its ambitions. Failures are after all often more instructive than successes. To experience Nine Princes in Amber, an interesting blend of both, feel free to download the Commodore 64 version here.