In 1976 Byron Preiss Visual Publications initiated a series of what we would call today graphic novels that have gone down as a landmark in comics circles. Each volume in the Fiction Illustrated line was a standalone story that replaced superheroes or anthropomorphic animals with hard-bitten detectives or space explorers “in the Star Trek tradition.” Preiss himself coauthored three of the first four books, and planned to work with another young writer named Michael Reaves on the fifth, an epic fantasy to be called Dragonworld. But the Fiction Illustrated line did indeed prove to be ahead of its time. Sales were disappointing, and his publishers weren’t interested in continuing the line. Undaunted, Preiss and Reaves turned Dragonworld into a more conventional fantasy novel, albeit one complemented by some fifty delicate pencil illustrations courtesy of Joe Zucker which Preiss and Reaves considered so integral to the project that they billed Zucker as essentially an equal partner. They all ended up living together in the same apartment for a time so as to work more efficiently on a novel that at more than 500 pages became an epic indeed.

Published in 1979, Dragonworld is the story of two lands, Fandora and Simbala, who are duped by festering resentments and disastrous misunderstandings into declaring war on one another. It’s left to a mismatched pair of adventurers — Amsel of Fandora, a retiring naturalist, and Hawkwind of Simbala, a warrior and leader — to join forces and find the truth: that the mythical colddrakes have in fact invaded both lands since the Last Dragon, normally the master who controls them, has been imprisoned. Dragonworld is in some ways an odd book in that it doesn’t quite fit comfortably into a category. The name, the look, and often the tone suggest a young-adult novel, an impression reinforced by the idealistic core message of “if we would all just take the time to talk and understand each other…” (Certainly it’s no great leap to see Fandora and Simbala as the United States and the Soviet Union.) But prior to Harry Potter kids’ books didn’t routinely stretch beyond 500 pages. And the story can also be grimmer than was the norm for a young-adult book circa 1979. In the first chapter we meet the perky young Johan and follow him on his grand first flight with a Flying Wing. We assume he’ll be our Bilbo surrogate — until Preiss and Reaves kill him violently to close the chapter.

Honestly, however, that may be the most interesting thing I can say about the book. It’s competently written and carefully plotted and the pictures are lovely, but at root it’s just another Tolkien derivative to me, not the sort of thing I can get all that chuffed about either way. So, I’ll leave it to those who are more invested in its genre to sing its praises or lament its flaws and move on.

The book was by all indications a moderate success, but hardly a genre landmark like Rendezvous with Rama or Fahrenheit 451. Still, securing the rights certainly wouldn’t be a problem, and would give Preiss the chance to write the sequel which the ending of the novel vaguely hints at. He even convinced Michael Reaves to join him again.

Dragonworld seems the most traditional of the Telarium games, what with being a quest narrative set in a fantasy world. Its story is a sequel to that of the novel in about the most unimaginative way it can be. It seems the Last Dragon had managed to get himself captured yet again, a fact he communicates to you, Amsel, via the Dragonpearl he gave you in the novel. And so you’re off again to fetch Hawkwind and journey with him down the length of Simbala to the Last Dragon’s place of captivity.

Traditional as it is, Dragonworld is also the best Telarium game I’ve yet written about. It’s not that it’s radically different, mind you. The parser still leaves much to be desired; “Try rephrasing this” is the error message you’ll come to hate this time. And the game is painfully slow to respond even when it does understand what you’re trying to say to it, especially on the Commodore 64 with its famously slow disk drive (the platform which otherwise, thanks to its graphics and sound capabilities, gives by far the best experience). The nadir comes in the form of three almost inconceivably awful action games, none of which would be likely to pass muster as a BASIC type-in magazine listing and one of which just might be the worst program I’ve ever actually seen somebody ask money for. How bad is this thing, you ask? Well, it’s so bad I was at first sure I must have a corrupted disk. It’s so bad that all of the action slows down to half speed every time you push the joystick, which is an especial problem because the whole game is already running in unbelievably slow motion. It would at least be simple to beat — if only the collision detection wasn’t often off by a whole sprite’s length or so.

The only saving grace is that this game and one of the others are completely irrelevant, unnecessary to play at all to complete Dragonworld. They simply appear like the worst non sequitur in history when you innocently wander into certain locations. Then, when you win or die — it makes no difference which — you’re dropped back into the text adventure, with no acknowledgment whatsoever of… whatever that was… that just happened to you. One of these horrors, however, is used to earn needed money in a casino, and can’t be avoided — theoretically. I got so annoyed with it that I used a hex editor on a save file to give myself the gold I needed, an exercise in tedious trial and error that was nevertheless far more fun than playing the gambling game would have been. As with Rendezvous with Rama, Telarium ripped all of these games out of later releases of Dragonworld, the best single decision they ever made to counteract their worst of putting them in in the first place.

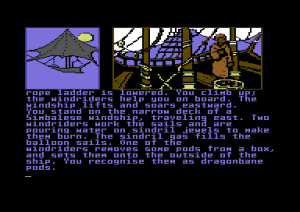

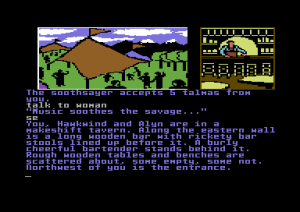

It’s thus high praise indeed for me to say of the rest of the game that it managed to overcome all that and leave me with a good feeling toward it in spite of itself. There’s a charm to Dragonworld that’s missing from Rendezvous with Rama entirely and that’s undone by a fatal flaw or two in the otherwise worthy Fahrenheit 451. While the genre and plot structure may be superficially the most traditional of the Telarium games, Telarium’s promise to make games that were more about the fiction than the puzzles is not just lip service here. You pick up Hawkwind very early in your quest, and so have a companion from then on. If you try to do something for which the brawnier Hawkwind is better suited, like, say, attacking a monster, the action automatically passes to him. This is a bit weird conceptually in the same way it was in Sierra’s The Dark Crystal, but given the parser limitations it works fine really. Combine Hawkwind’s presence with the creatures and people you meet everywhere and the fact that you can even get a third companion to accompany you and Hawkwind for much of the game, and adventuring in Dragonworld is a far less lonely experience than the norm.

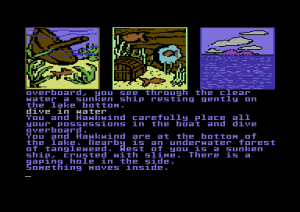

Dragonworld is made up of a long linear series of obstacles, until you arrive at the town of Kandesh, where you can roam freely to prepare yourself for the (once again linear) climactic scenes. The puzzles are always realistic problems grounded in the story and the environment, and can usually be solved in straightforward, realistic ways. If you’re one of those people like me who often wonders why you can’t just bash that troll in the chest instead of paying him his coin and then waiting for him to go to sleep and then casting some magic spell on him to get the coin back and ad infinitum, this is a good game for you. Indeed, Dragonworld‘s puzzles are fairly trivial to solve in the early going in particular. By the time you’re approaching the Last Dragon’s prison they’ve gotten more difficult — two or three are genuinely tricky — but overall Dragonworld is by far the easiest of the first batch of Telarium games. It takes almost a willful effort to lock yourself out of victory. Even during the climax you can backtrack almost to the starting location if you find you’ve left anything undone. This may not do much for dramatic tension (imagine Frodo at the Crack of Doom: “Sorry, Sam, it seems I’ve left something behind. Let’s just nip quickly back to the Shire, then come back and try this again.”), but it certainly makes for a less frustrating game. Likewise the primitive parser, while still prone to non sequiturs and fits of stubbornness, is used more wisely and made more generous in its interpretations this time. It’s seldom more than a momentary frustration.

Most of all, Dragonworld is just a fun world to inhabit for a while. The sound and especially the graphics actually justify their inclusion for the first time in a Telarium game. The latter were drawn by a relatively well-known artist, John Pierard. His work is bright, welcoming, and attractive even given the limits of the computers on which Dragonworld had to run. They add much to the experience, making the game feel like the grand fantasy romp it wants to be.

Overall, then, Dragonworld just comes together in a way that the previous two Telarium games I’ve written about do not. It’s hard to say exactly why this happened. Having the authors of the novel actually working on the game as committed, engaged writers and designers certainly couldn’t have hurt. And maybe, since it was Preiss’s company after all, his game got just that little bit extra: the best artist and composer, a little more testing, etc. Who knows? The important thing is that Telarium finally began to deliver on some of their promises here.

That said, I won’t lie to you: it’s still a much more unrefined experience than an Infocom game of similar vintage. But if you’re willing to work a little bit harder for your fun, there’s still much to be had here. Some annoyances can even be somewhat alleviated in modern times. Set your emulator to (at least) 200% speed, for example, to make the long parsing delays a bit more tolerable. As usual, you can download Dragonworld from right here.