At the beginning of Fahrenheit 451 the game you learn that the nuclear apocalypse that ended the book turned out to not be so apocalyptic after all. It seems the country just got knocked around a bit. Now you’re in New York City looking to continue your rebellion against the book burners in charge of things and hopefully in the process rescue Clarisse, whom your sources tell you is still alive and being held prisoner somewhere in the city; it seems she’s gone from Manic Pixie Dream Girl to hardened resistance fighter.

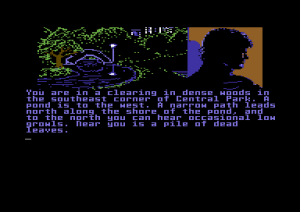

Going west or north from the starting location gets you instantly killed by some of the fauna that now inhabits Central Park. Obviously that pile of leaves must be the ticket. Or is it?

>move leaves

Can't understand that.

>look under leaves

This is the southeast corner of Central Park. There is a clearing, with a pond to the west and a path leading north along the shore of the pond.

>push leaves

Can't understand that.

>get leaves

Nothing happens.

After ten more minutes of this sort of thing, you might find the magic verb at last…

>kick leaves

Under the leaves you see an old, rusted grating set into a patch of broken concrete.

To call this beginning of Instadeath combined with Parser Fun inauspicious hardly begins to state the case. What a surprise, then, when the game that follows turns into a worthy design with exactly the spark of passion and innovation that is so conspicuously missing in Rendezvous with Rama. If only the parser didn’t continue to undermine it at every turn…

Byron Preiss and Ray Bradbury first worked together on a book called Dinosaur Tales, which combined a number of old and new Bradbury stories on one of his favorite subjects with Preiss’s signature approach to books as lavishly illustrated objets d’art. When the Telarium project began, Preiss was able not only to convince him to sign a contract for the adaptation of his most famous book but also to involve himself in the project a bit more than Arthur C. Clarke would in Rendezvous with Rama: he wrote a summary of the book to be printed inside the game box, and did some interviews just to promote it. Telarium claimed that he also contributed “ideas” to the project, although that phrase is vague enough to mean almost anything; he did frankly state in one interview that he “wasn’t interested in doing the work himself,” would “trust his longtime friend Preiss to render the work faithfully.”

So, Fahrenheit 451 the game fell to Byron Preiss Video Productions, the shell company he and Spinnaker had set up that also created Rendezvous with Rama and Dragonworld from scratch. Preiss installed another veteran of his Be an Interplanetary Spy book series, Len Neufeld, as designer and writer. Being built with the same technology and employing many of the same programmers, artists, and composers as Rendezvous with Rama, Fahrenheit 451 is inevitably superficially similar in flavor to that game. Certainly the two games have plenty of disadvantages in common, including a stubborn and uninformative parser (the slightly less infuriating “Can’t understand that” replacing “You reconsider your words” as Fahrenheit 451‘s error message of choice) and pictures that sometimes look like little more than a smear of discolored pixels (with an ugly brown replacing an ugly blue as Fahrenheit 451‘s hue of choice). Fahrenheit 451 at least lacks Rendezvous with Rama‘s horrid action games. More importantly, it acquits itself far better by engaging with the themes and ideas of its source material rather than just the window dressing of stage set and plot outline. As blogger Dale Dobson noted in his post on the game, it “takes itself, and its inspiration, seriously, and that is to be commended.”

By making the game a sequel to the novel rather than a recreation, Neufeld is freed to create a design that plays in Bradbury’s world with many of Bradbury’s themes but that also works as an adventure game. You have the run of about twenty blocks of Fifth Avenue in Manhattan, an area the team knew well; New York City was the home of Neufeld, Preiss, and most of Preiss’s people. By setting the game in his home town and including famous landmarks like the Plaza Hotel and Tiffany’s, Neufeld manages to make the setting of Fahrenheit 451 feel like a real place, an impression aided by just enough elements of simulation: time passes and day cycles to night, Mechanical Hounds patrol up and down the street on a regular schedule, stores open and close and people come and go from their apartments. You must also eat occasionally and manage your money (which you’ll also need to find more of to complete the game).

The writing is more than solid; it’s sometimes downright lyrical. It’s not afraid to stretch to several paragraphs when the situation calls for it and never feels written down to a computer-game audience. Exploring the world, always one of if not the core pleasure of adventure gaming, is especially pleasurable here, as is solving a collection of interesting puzzles that are always logical and fair. Your ultimate goal is to penetrate the New York Public Library. Your immediate reason for doing so is to rescue Clarisse, who is being held prisoner there, but the goal also has symbolic significance in a game all about the pleasures and importance of books. No, there’s not much of a real story to speak of beyond that goal. And yes, there are a hundred problems I could poke at if we insist on judging the game as a coherent work of fiction, like the way that just about everyone in the whole city seems to be in the Underground, or how Clarisse now seems to be an entirely different person from the one we knew in the book. But this isn’t a book. It’s an adventure game, whose pleasures are anchored in exploring a landscape both physical and mental rather than plot. And the mood of the book is always very present. At the end, you must choose between abandoning the cause and enjoying life with Clarisse or sacrificing yourself on the altar of Literature, a perfect echo of the book’s contrasting of the comfort and superficial happiness of (Bradbury’s perception of) television with the dangerous ideas of the great books.

Many of the puzzles are of the conventional object-oriented stripe — you need this to do that, but to get it you need to find a way to do this, etc. — but the central spine of the design once again finds a way to connect with the themes of the book. You need the assistance of the various members of the Underground who are scattered around the city, but talking with them usually requires a password in the form of a literary quotation. So you spend a lot of your time hunting down and deploying these quotations, which run the gamut from the Song of Solomon to Moby Dick to the inevitable four from Shakespeare. In purely mechanical terms, it’s just another system of magic words, no more complicated or interesting than Adventure‘s PLUGH and XYZZY. Thematically, however, it’s brilliant, especially because the quotes always have something to connect them to the situation or person on which they must be used — even if that something is sometimes only obvious in retrospect. Many were supposedly chosen by Bradbury himself. Indeed, whatever his actual involvement with the development of Fahrenheit 451 the game, Bradbury the author is thoroughly present in it.

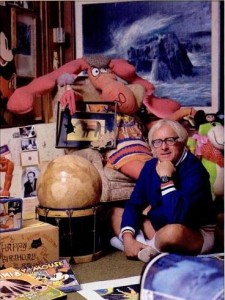

I actually mean that literally as well as metaphorically. Amidst lots to do and discover, you can find “Ray’s” phone number and call him up. He helps with a puzzle or two directly, but also shares his thoughts on any of the literary quotes you care to ask him about, and will shoot the breeze in the form of a random anecdote if you just TALK TO him. I generally don’t have a lot of patience with the man-child persona Bradbury had by this time well established for his many interviewers. I find it affected and, well, childish, and his art, also long since established by 1984, of sounding profound without actually saying anything drives me nuts. There’s some of that here, but Neufeld and company curate him pretty well; he’s actually fun and interesting to listen to. Most of his responses are phrased as if he’s answering a question you just posed — a neat, verisimilitudinous trick that requires a mere modicum of suspension of disbelief.

We’re all terminally ill. Sickness is merely a factor, like money.

Japanese, Italian, French, Chinese, and other East Asian (Thai, Korean, Philippine, etc.), Middle Eastern — when you`re hungry, everything`s good.

Favorite films? King Kong, Fantasia, Citizen Kane.

I told you — my favorite play is St. Joan.

Moby Dick, Tarzan, and Grapes of Wrath are my favorite books. I also love the stories of Hemingway and Poe.

Many of my early stories were published in the magazine Weird Tales in the early thirties and forties.

My love affair with dinosaurs has lasted as long as my affair with Mars.

Such little extras abound. You can REMEMBER snippets of prose from the original novel; in addition to Ray, you can also call many other people from the handy phone booths, most of whom aren’t strictly needed but all of whom add a touch of atmosphere or something to think about; there are alternate solutions to puzzles and many paths to victory.

I wish I could wrap up this article right here, with the final note that, while I find Fahrenheit 451 the novel rather overrated, this game is not only great fun to play but also left me feeling a bit more kindly disposed toward its inspiration and even its inspiration’s author. Alas, I can’t do that, for reasons I first broached at the beginning of this article.

The parser, you see, ruins everything. Telarium wants and claims it to be a full-sentence jobber to rival Infocom’s, but it barely seems to parse at all, just to match arbitrary sequences of words. (Yes, I have to take back what I said in an earlier article about Telarium’s parser being “adequate.”) The fact that it will accept more than two words just compounds the problem, adding a nice dose of combinatorial explosion when you’re trying to figure out what to type at the thing. Worst of all, it’s not consistent in its whims. Sometimes you must TALK <character>; sometimes you must TALK TO <character>; sometimes you must ASK <character>. Synonyms are virtually nonexistent. There’s a character named Emile Ungar whom you can only refer to as “Ungar” — not “Emile,” not “Emile Ungar.” Similar situations are absolutely everywhere. I was having a great experience with the game until I got stuck and turned to the walkthrough, whereupon I found that I had actually solved every single puzzle I’d found so far. I just hadn’t typed the exact phrasing that the parser wanted.

I can hardly express how disheartening this is to me. At one point I was ready to call Fahrenheit 451 the best non-Infocom adventure game I’d yet played for this blog. Now I can’t even really recommend it at all. What’s doubly frustrating is that the game doesn’t absolutely need a better parser per se; none of these puzzles require complicated parser interactions. Telarium just needed to put the game before testers for a week or so, to note what they tried to type and add those phrasings to the pattern matcher. As it is, it feels like a game that only its creators, who had the magic phrases wired into their subconscious, actually played. For a clue to how that could have happened, we might turn to a Harvard Business School study that describes the frantic push at Spinnaker to get the new line out in time for Christmas 1984. In the words of their chairman Bill Bowman:

We had people working 24 hours a day for a month. We converted the board room into a dormitory, with sleeping bags and pillows. People would work until they couldn’t go on anymore, and then they would go upstairs, sleep for a few hours, come down and start working again. We had a caterer bringing in meals for a month, weekdays, Saturdays and Sundays. It was… ridiculous, that’s what it was. But, we had to have the product in a month. We did meet the deadline, but we won’t do it again. It was extremely painful, although when it was finished, the camaraderie that existed in the team was fantastic. This involved some 30% of the people in the company. I think this is going to be our biggest line next year.

It’s hard to imagine this situation allowing for much testing. This leads to an important point: Infocom is justly celebrated for their ambitious, imaginative writers and designers. Yet it’s also true that they were far from the only such talented folks working in text in the 1980s. Infocom’s triumph was, as much as anything else, a triumph of process, of a commitment to quality and doing things right even if that meant taking the slow, plodding route of releasing a game every few months rather than vomiting out half a dozen on the eve of Christmas. Infocom’s games didn’t suffer from the problems of Fahrenheit 451 because Infocom never allowed themselves to get into a situation like the one described above — a situation which, whatever its value in adrenaline and company camaraderie, doesn’t often lead to the best games.

Still, Fahrenheit 451 does do enough things right, and has enough interesting innovations, that you may want to spend some time on Fifth Avenue. As an expression of the joys of literature it works for me better than the book. By all means feel free to download the Commodore 64 version and give it a shot if it looks tempting.

(The same references I used for my introduction to Telarium and bookware mostly apply here. The photo of Bradbury was part of an interview to promote Fahrenheit 451 the game in the June 18, 1984, issue of InfoWorld.)