Ray Bradbury enjoys by far the best literary reputation amongst science-fiction writers of the Golden Age. Certainly he’s the only one you’re likely to find on a high-school English syllabus. If you’re feeling cynical, you can attribute much of his reputation to a chance meeting with Christopher Isherwood in a bookstore in 1950. When Bradbury showed considerable chutzpah in pushing a signed copy of his book The Martian Chronicles upon him, Isherwood for some reason actually read it and wrote a glowing review heralding this “very great and unusual talent.” “I doubt if he could pilot a rocket ship, much less design one,” wrote Isherwood, thereby granting Bradbury his bona fides as a suitably scientifically inept literary writer, and making him the only science-fiction writer it was acceptable for the intelligentsia to read despite a bibliography that consisted mostly of the likes of Thrilling Wonder Stories and Weird Tales.

But of course attributing Bradbury’s reputation entirely to one English intellectual’s approbation would be unfair. He was — or eventually flowered into — just about the only one of his peers aware of a deeper, richer literary tradition than the one that began with the first issue of Amazing Stories in 1926, the only one who tried to craft beautiful — as opposed to merely functional — prose. He has some entertainingly pulpy adventure stories to his credit and some more labored but lyrical stories, as well as one novel of childhood, Dandelion Wine, that isn’t science fiction at all. Still, his bibliography of truly canonical works is fairly thin for an important writer who claimed to have written every single day for more than seventy years. For all his continuing literary reputation, most of his work after 1962’s Something Wicked This Way Comes was politely received and just as quickly forgotten amongst both genre and literary fans.

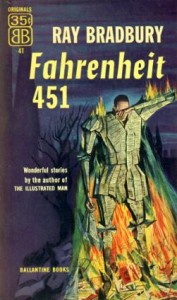

Bradbury’s most famous work, Fahrenheit 451, dates to 1953. It’s a book which kind of fascinates me but also frustrates the living hell out of me. If you somehow escaped it in English class, know that Fahrenheit 451 is the story of a fireman named Guy Montag who lives in a future where that profession doesn’t mean what you think it does: firemen now start fires rather than put them out. Specifically, their mission is to burn books, which never caused anyone anything but trouble anyway and have now been replaced by television and other more easy-going entertainments. This mission is considered so essential that houses are built from a special flame-proof material, not out of concern about conventional fire safety but because it makes it easier for the firemen to come and burn any stray books with a minimum of fuss. Because every dystopian novel needs a doomed rebel against the system, Montag grows disillusioned with his profession, and eventually joins the literary underground struggling to keep the flame of knowledge alive. His means of disillusionment is — in another fine dystopian tradition — a girl, a teenage neighbor named Clarisse. And this is where I first start to get really annoyed. Bradbury has been credited, with some truth, with foreshadowing or even inspiring everything from 24-hour news as entertainment to the Sony Walkman in Fahrenheit 451. I’ve never, however, seen him properly credited for his most insidious creation: the Manic Pixie Dream Girl.

The Manic Pixie Dream Girl was first labelled as such by Nathan Rabin in a review of the movie Elizabethtown for the Onion’s AV Club. She has no real existence of her own; we never learn her hopes or fears or anything of her inner life. Her whole purpose rather revolves around the brooding male she has apparently been sent from Manic Pixie Heaven to save through the sheer force of her quirky charm. “The Manic Pixie Dream Girl,” Rabin writes, “exists solely in the fevered imaginations of sensitive writer-directors to teach broodingly soulful young men to embrace life and its infinite mysteries and adventures.” We can add “sensitive young science-fiction writers” to that sentence.

The rain was thinning away and the girl was walking in the center of the sidewalk with her head up and the few drops falling on her face. She smiled when she saw Montag.

“Hello!”

He said hello and then said, “What are you up to now?”

“I’m still crazy. The rain feels good. I love to walk in it.”

“I don’t think I’d like that,” he said.

“You might if you tried.”

“I never have.”

She licked her lips. “Rain even tastes good.”

“What do you do, go around trying everything once?” he asked.

“Sometimes twice.” She looked at something in her hand.

“What’ve you got there?” he said.

“I guess it’s the last of the dandelions this year. I didn’t think I’d find one on the lawn this late. Have you ever heard of rubbing it under your chin? Look.” She touched her chin with the flower, laughing.

“Why?”

“If it rubs off, it means I’m in love. Has it?”

He could hardly do anything else but look.

“Well?” she said.

“You’re yellow under there.”

“Fine! Let’s try you now.”

“It won’t work for me.”

“Here.” Before he could move she had put the dandelion under his chin. He drew back and she laughed. “Hold still!”

She peered under his chin and frowned.

“Well?” he said.

“What a shame,” she said. “You’re not in love with anyone.”

I’m sure that for certain people — probably mostly romantic boys of about the age when Fahrenheit 451 is most often assigned in school — Clarisse reads as delightful. As for me, I find it hard to believe that a married 33-year-old man wrote this tripe that sounds like something I might have written for my high-school creative-writing class. Even making due allowance for different times, passages like this make it hard for me to see Bradbury as the serious writer Isherwood and others would have me believe him to be.

But if we don’t want to place Bradbury alongside Joyce and Orwell as one of the twentieth century’s greatest, what do we want to do with him? I tend to go down the same road as Bryan Curtis, who claimed that Bradbury was not so much a great writer full stop as a great pulp writer. Fahrenheit 451 is… well, it’s a silly book really. This is a world where Benjamin Franklin is honored as the supposed first book burner; where a bunch of maintenance workers who if they lived in our world would be changing the oil in your car come out to do a quick blood exchange on someone who’s taken a few too many pills; where teenage joy-riders run over pedestrians just for fun with no consequences; where semi-robotic, semi-organic Mechanical Hounds chase fugitives through the streets. All of this is described in luridly purple prose that wouldn’t be out of place in a Roger Corman script — or a computer-game instruction manual. A Mechanical Hound, resting after a hard day on the job: “It was like a great bee come home from some field where the honey is full of poison wildness, of insanity and nightmare, its body crammed with that over-rich nectar and now it was sleeping the evil out of itself.” You’re trying way too hard, Ray…

It’s all so over the top that it makes Fahrenheit 451 kind of fun to read, despite the fact that there’s not a hint of conscious humor in the book. Compared to the masterpiece of dystopian literature, Nineteen Eighty-Four, it’s just not even operating on the same level. Orwell’s world is horrifying because it is believable; Bradbury’s is anything but. Every sentence Orwell writes is taut, considered; Bradbury just sort of gushes everywhere, piling on the adjectives until sentences threaten to buckle under their weight. The same goes for his other building blocks: he piles on a nuclear war from out of nowhere at the end of the book because, hey, why not add to the dystopian litany? I’m not sure I’m prepared to accept that Bradbury was a better writer than Clarke, Asimov, or Heinlein. I just think he was trying harder to be a good writer (in the sense that would lead to acceptance by Isherwood and his peers) than they were. Bradbury post-Isherwood dearly wanted to leave the pulps behind; he allegedly begged his publisher to remove the words “science fiction” from his books entirely. Yet the pulps remained at the core of who he was as a writer, at least when he was at his best. The Martian Chronicles (1950) and The Illustrated Man (1951) are my favorite books by him because their style is still easy, relatively unaffected by the call to Literature. Fahrenheit 451, unfortunately, often all but buries its pulpy fun elements underneath all that bloated verbiage.

Still, it’s possible to read Fahrenheit 451 as neither an endeavor in serious world-building nor pulpy adventure, but as an allegory about the threat posed to books and, well, thoughtfulness in general by mass media and the technology that enables it — as, in other words, Bradbury’s version of Animal Farm rather than Nineteen Eighty-Four. Certainly this is the most sympathetic way to approach it today if we’re determined to label it Great Literature, even as we remain in doubt whether that was really Bradbury’s intention.

Bradbury was always more than a bit of a Luddite. In later years he railed against the Internet and computers as only a reactionary old man can, displaying breathtaking ignorance in saying a computer was nothing but a glorified typewriter, and he already had two of them. Similarly, his target in the 1950s was television. Yes, there are ways in which Fahrenheit 451 feels shockingly prescient: the clamshell earphones people use to isolate themselves from the world even when out and about in public; the elaborate home-theater setups in every house; the ATMs. And the questions Bradbury raises are profoundly worth asking still — in fact, more than ever — today, when everyone seems more and more wedded to their Facebook and Twitter accounts and less and less able to just enjoy the proverbial breeze on their cheeks, able to simply be in the non-electronic world of people and physical sensation. It’s also important to note that the dystopia of Fahrenheit 451, unlike that of Nineteen Eighty-Four, is a populist dystopia. The people have brought this world upon themselves, and fundamentally want things to be this way.

But of course for every point on this chain of thought there’s a counterpoint. If Twitter is a network of narcissistic celebrities and would-be celebrities tweeting about what they had for lunch, it’s also a way for activists in totalitarian countries to communicate outside the reach of the government. If email and the Internet isolate us from our neighbors, they have also opened up a new era of international communication and understanding, not just among the elites and heads of state but amongst ordinary kids in high schools and universities around the world. Perhaps the kindest thing I can say about Fahrenheit 451 in what I know has hardly been a glowing review is that it can lead us to think about these issues seriously. That Bradbury saw so much of the future in which we now live in 1953 is indeed remarkable. I just wish all of his arguments about it weren’t so muddled.

I’m a huge lover of books, so I ought to be very sympathetic toward Fahrenheit 451‘s defense of literature. Actually, however, I find it rather wrong-headed in that it misses everything that is personally important to me about literature. The rebellion that Montag finally joins at the end of the novel is made up of aging professors and other erudite types who have each memorized a classic work of literature, to be passed on to future generations of rebels and preserved until humanity decides it is ready for it again. Beyond representing a wonderfully interesting game of Chinese whispers, this scheme bothers me because it treats books as objects to be mothballed away, a static canon of Great Works held sacrosanct. It’s another sign of the conservative, even reactionary viewpoint from which Bradbury writes — a viewpoint I just don’t share and don’t ever want to. I’m for a living literature of creativity and reinvention; I’d rather watch a bunch of Italian prisoners put on an earthy performance of Julius Caesar that really matters to their own lives than watch a meticulously researched reproduction of the Elizabethan theater experience put on by a bunch of fussy scholars — to say nothing of those bores who pride themselves on pulling out an out-of-context Shakespeare quote for every occasion. Bradbury’s rebels should be spending at least as much time creating new books as preserving those that have gone before. The health of a culture is measured not by the size of its museums but by the creative life out there on its streets. And no, the irony of someone who calls himself the Digital Antiquarian writing this is not entirely lost on me. Suffice to say that museums and preservation are important too, but will never be as beautiful as a kid who picks up pen, paintbrush, instrument, or computer for the first time.

Bradbury continually confuses books as physical objects with the idea of books or, if you like, ideas. Frustratingly, at times he does seem to get the distinction:

Books were only one type of receptacle where we stored a lot of things we were afraid we might forget. There is nothing magical in them, at all. The magic is only in what books say, how they stitched the patches of the universe together into one garment for us.

In another place he rails against what a later generation would come to call political correctness:

Colored people don’t like Little Black Sambo. Burn it. White people don’t feel good about Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Burn it. Someone’s written a book on tobacco and cancer of the lungs? The cigarette people are weeping? Burn the book.

Yet, as he himself noted in the more lucid passage that precedes this one, all of these ideas can be conveyed by other means than paper and print. Nor are all books by some inherent property of the form challenging or enlightening. The bestseller rolls and airport newsstands are filled with volumes that are neither. And what of challenging films, television, even, yes, computer games? How are these things controlled when the firemen are obsessed only with paper books, any and all of them? With all due respect to Marshall McLuhan, the medium is not always the message.

Fahrenheit 451 is a stew of conflated ideas about censorship, the decline of reading, technology, media, government, nuclear apocalypse, even automobiles. Heady, worthwhile topics all, but it’s hard to pull one thing apart from another, hard to extract a cogent point of view on anything. Perhaps the book’s secret weapon is that it’s hard to find anything solid enough in this amorphous mass to really kick against. Bradbury himself became an expert at weaving and dodging through criticisms of the book as times and interlocutors changed. One year he was writing an afterword that was all about censorship in current times; a few years later Fahrenheit 451 wasn’t about censorship at all. The only ideas we can fully get our hands around are thoroughly banal: books are good, burning them is bad; everything’s going to hell with the younger generation.

The latter has been key to the book’s popularity with disgruntled authority figures everywhere, just as the pulpy fun and melodrama makes it appealing to teenagers. If it’s not ultimately a great book, it’s certainly one with something to appeal to a lot of different people, which made it a pretty good target for adaptation into a commercial computer game. We’ll see how that fared next time.