By the time the IBM PC was a year old in late 1982, it was clear that the machine was a huge success. IBM had sold some 150,000 PCs during that first year, and demand continued to increase almost exponentially. As the PC blew right through sales forecast after sales forecast, IBM scrambled desperately just to meet demand. An interview with Don Estridge, head of IBM’s Entry Systems Division that was responsible for the PC, in the November 1983 Byte describes the chaos of those heady first couple of years:

Each quarter, IBM asks everyone who is selling the PC for a projection of purchases for two periods: the next quarter and the three quarters following it. In October 1982, for example, the division asked customers how many systems they expected to buy for the period from January through March 1983. Then IBM asked these customers what they expected to buy for April through December 1983.

When customers returned in January of this year [1983], ostensibly to talk about their system needs for April 1983 and beyond, they wanted to talk about January through March all over again. They doubled their orders for that first quarter.

“Then the same darn thing happened again in March, when we were talking about July through September. We can only handle so many factors of two,” Estridge says. “We’ve upped our production rate three times this year; production is very high. We’re extremely pleased that we can build a quality product at that rate, but it’s not enough. If the demand keeps on going at these rates,” Estridge warns, “at some point there won’t be any more parts.”

The IBM PC wasn’t just a commercial success; it was a transformative landmark for the PC industry as a whole. The vast majority were purchased not by the hackers, hobbyists, and early adopters who had heretofore driven the PC industry, but rather by the mainstream of corporate America, conservative businesses who were as nonplussed by its relatively high price as they were soothed by the legitimizing imprimatur of IBM. Both were taken as signs that the IBM PC was a serious machine, qualitatively different from the scruffy likes of Commodore, Atari, Radio Shack, and even Apple. Big Business placed huge orders that could reach into the multi-millions at a single pop. Merrill Lynch, for instance, went overnight from being dismissive of computerized trading to ordering a machine for the desk of every single broker in the company — 12,000 computers. Such was the power and mystique of IBM, the number-one company in the world in after-tax profits, a company whose gross sales exceeded the budget of the state of California.

And all of that was starting to happen even before the IBM PC got its killer app, the second such to hit the PC industry as a whole: Lotus 1-2-3. Introduced in January of 1983, 1-2-3 was, like the first killer app VisiCalc, a spreadsheet program. But 1-2-3 was clearly better in just about every possible way, to the extent that it made VisiCalc a has-been virtually overnight. Mitch Kapor, head of Lotus, had made the decision to throw in his lot entirely with relative newcomer IBM, not bothering to make a version of 1-2-3 for the Apple II or the CP/M machines or anything other than the IBM PC running Microsoft’s MS-DOS. Just as the Apple II had gotten a huge boost from being the first machine to run VisiCalc, that first clearly useful piece of PC software for the everyday businessperson, the IBM PC soared on the back of Lotus 1-2-3. For CP/M and the vendors still supporting it with hardware and software, meanwhile, Kapor’s decision marked the definitive beginning of the end. By 1985 CP/M would effectively be a dead operating system. Businesspeople simply had no use for a computer that couldn’t run 1-2-3.

An interesting and too little remarked aspect of the transformation wrought by the IBM PC is that IBM themselves never planned it or saw it coming. They themselves, in what amounted to a rare display of corporate humility, underestimated the impact that the IBM name would have on the industry. Instead of arrogantly going their own way and defining their own standards, which had always been their wont with their bigger computer systems, with the PC they made an apparently sincere effort to fit into the existing ecosystem. They even dutifully tried to license and adopt CP/M as their standard operating system until losing faith in Gary Kildall and Digital Research and going with Microsoft’s CP/M lookalike MS-DOS. A quick glance at a sales brochure for the original IBM PC reveals a plethora of features that had little relevance to the workaday world of business computing: an optional color graphics card (not a great one, but notable for existing at all); sound (ditto); a joystick interface card; a BASIC environment built into ROM, which could be used in lieu of a disk-based operating system; a cassette-drive port; the possibility of connecting the machine to an ordinary television in lieu of a monitor; and the possibility of buying it configured with as little as 16 K of memory. Far from being a honed weapon for business-computing domination, the IBM PC was designed to be generalized and flexible, adaptable to many different roles in the same way as, say, the Apple II. When Big Business jumped all over it, it seems to have surprised IBM as much as anyone.

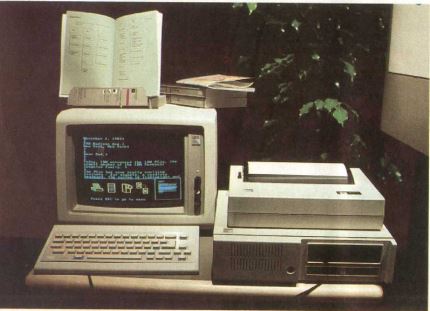

Which is of course not to say that they were complaining about it when it happened. As it became clear how the IBM PC was perceived and where it fit, IBM initiated development of a next model that excised many of the aforementioned phantom limbs while giving business users more of what they had liked about the original. The PC/XT, introduced in March of 1983, came with a still slightly exotic (and expensive) 10 MB hard drive as standard equipment, and was an all-around bigger, beefier contraption with eight expansion slots rather than five, more standard memory, and a larger power supply to fuel it all. Another model in development, code-named “Popcorn” and due to be introduced early in 1984, was a portable — today we would say (at best) “luggable” — version for the businessperson on the road. Having served Big Business’s computing needs for years with their larger machines, IBM was in their element here as well, at least once they figured out what was happening and where their machines fit.

And yet, despite all of this success, the failure of the PC to really make a dent in other areas did rankle a bit. While the IBM PC had created a whole new market category for microcomputers, said category wasn’t the only new one. Shortly before the PC arrived, Commodore had introduced the VIC-20, an inexpensive machine pushed not as a tool for hackers or hobbyists but as a friendly machine to be used in the home by casual users for education, light productivity applications, and of course entertainment. The VIC-20 was a huge success, redefining Commodore’s corporate image forever (both for better and for worse in the long run), and opening the category of the “home computer” as a mass-market phenomenon. This in turn brought the venture capitalists and the would-be computer-entertainment moguls, not to mention a torrent of competitors and the Home Computer Wars of 1983. Suddenly the base of hackers and early adopters who had both built and been the customers of the microcomputer industry prior to 1982 or so were a minor factor, almost irrelevant, as everyone raced either upward to the business PC (where the big winner was of course IBM) or downward to the home computer (where the big winner was Commodore). Only Apple was left perched, not entirely comfortably, somewhere in the middle; the Apple II intersected the high end of the home-computer sector along with the low end of the business market, while also remaining the computer of choice in schools and a great favorite of the hackers who had built the industry.

The home-computer market was both much more price sensitive and much more crowded than the business market, and thus couldn’t hope to match the business market in sheer moneymaking potential. Commodore sold many more machines than even IBM in 1983, but didn’t make more than a fraction as much from the effort despite edging out Apple in total earnings for what would turn out to be the last time in their history. (This disparity in earning potential explains why Apple was so desperate to find a way to fully penetrate the business market with the Apple III, the Lisa, and finally the Macintosh.) Given this reality, it may seem odd that IBM concerned themselves with home computers at all. I believe we can point to a couple of factors here. First of all, home computers were simply an opportunity — perhaps not as big or juicy an opportunity as business computers, but who said a huge company like IBM couldn’t own both markets? All of the pundits were predicting that the home-computer market was only going to continue to grow, that in just a few years a computer would be as much a fixture in every home as a television and a stereo. That led directly to what we might call the public-relations motivation. If at all possible, all of those kids who would be growing up with computers in their homes should grow up with IBM computers. That way they would be inculcated into “the IBM way,” would be comfortable with IBM technology when they grew up and entered the business world, would seek it out when they got still older and were placed in charge of purchasing at their companies. One hand, as they say, would wash the other, realizing the goal of making IBM as synonymous with little computers as they were with the big ones.

This, then, was the reasoning that led to the machine code-named “Peanut,” IBM’s dedicated home computer. Development was well underway by the time of the PC/XT’s launch, and the project’s existence was, intentionally or unintentionally, something of an open secret with the press throughout 1983. The specter of IBM’s eventual arrival loomed over the chaos of the Home Computer Wars, over annual reports and long-term planning throughout the industry. Why shouldn’t the Peanut come to dominate the low end, said the conventional wisdom, just as its bigger siblings did the high end? Apple and Commodore and everyone else breathed a sigh of relief when the rumor mill revealed that Peanut, originally scheduled to appear just in time for Christmas, had been pushed back to early in the following year. At least they would get one more Christmas sales season — one which would actually turn out to be the biggest of all for some time to come, although they certainly didn’t know that — free of the IBM juggernaut. Then, in November of 1983, the Peanut was officially announced at last and prototypes shown to the press, in the hopes, some suspected, of making some of those would-be Christmas buyers hold off until they could have an IBM the following year. Journalists weren’t quite sure what to write about the machine they flocked to see at a special reception inside IBM’s Manhattan headquarters.

Much about the Peanut, now officially named the PCjr, was about what everyone had expected (feared?). While definitely, as its name would imply, a scaled-back version of IBM’s business machines, its available configurations of 64 K or 128 K of memory and 16-bit processor made it more than competitive with the Commodore 64 or Apple II in terms of sheer horsepower. It could boot to BASIC or, if you bought the optional floppy drive, MS-DOS, in which mode it could run a subset of IBM PC software that wasn’t too memory hungry. It offered 16-color graphics that were comparable to the Commodore 64 in some ways, although it lacked that machine’s sprites. It also had a pretty good three-voice sound chip, although, once again, not quite the equal of the Commodore 64’s SID. On the flip side, it could, like the newer Apple II models, display 80 columns of text compared to the 64’s 40, a feature that made it much more suitable than the 64 for word processing and other productive tasks. And it had one feature that really was ahead of its time: a wireless keyboard that let you kick back or sit wherever you wanted when you played the games that IBM hoped would soon be flooding the market. All in all, it all looked like a pretty reasonable effort, with the fit and finish and utility of the Apple II and most if not all of the audiovisual panache of the Commodore 64. It even had two — two! — cartridge ports for easy gaming. Coupled with the reputation and marketing resources of IBM, it looked like a very dangerous machine. And then you tried to actually type on the thing.

IBM, you see, had gone with a rubber “Chiclet” keyboard, like that of a cheap calculator — or the sub-$200 Radio Shack Color Computer. Its presence was all but incomprehensible. Contrary to what Apple zealots then and now might prefer to believe, IBM was not normally oblivious to ergonomics or aesthetics. While their machines were not sexy, they were generally functional and comfortable over many hours of use, and always had that reassuring feeling of “IBM quality.” IBM put considerable thought and research into what they called “human factors” when putting together the original PC. Indeed, they maintained in Boca Raton an entire laboratory devoted to ergonomics.

He [Estridge] points out that various human-factors considerations are reflected in the overall PC design that he says make the machine comfortable to use. The keyboard can be tilted, for example, to assume a flat-surface angle or a tilted-up angle. Estridge says both are standard angles that make users feel comfortable.

He also cites studies of eye-pupil dilation that influenced the PC’s design. He says these studies have shown that there’s a direct relationship between pupil dilation and fatigue; the more a user’s pupil dilates, the more fatigued he may become.

“If you can cut down on contrast changes as people use the equipment, you reduce the likelihood of frequent pupil dilation.”

How has this principle been applied to the IBM PC? Estridge explains it this way: “Imagine that the center of the machine is a high-contrast area and the outside of the machine — the background — is a low-contrast area. The machine has grades of contrast as you move from the screen outward. Its highest contrast is on the display tube. Immediately around the tube is a lower-contrast border, and then the cabinet curls round to form an even lower-contrast frame.

“The eye then progresses from seeing dark gray to light gray to medium white, and, beyond that, essentially a noise background. As the eye moves across those boundaries, it doesn’t experience much contrast change, and the viewer doesn’t get tired.”

Much about the PCjr has that same sense of attention to detail and quality. The cartridges, for example, have a foam lining that lets them slide gently but snugly into place with a feel that is, as one YouTube commentator puts it, “awesome.” IBM also added special tabs to the keyboard to lock an overlay into place. Their idea was that many — most? — PCjr programs would ship with one of these little cardboard cheat sheets that explained the purpose of every key on the keyboard, right above the key itself.

And yet, inexplicably, there were those dead rubber keys that seemed to invalidate all positive impressions and make the PCjr feel like a toy. Typing on the machine was, as one journalist put it, “a hateful experience.”

The other obvious concern was the price. The 64 K model with cassette drive would cost you almost $700; the far more useful and desirable 128 K model with floppy-disk drive $1250. Everyone agreed that IBM could likely get a surcharge for their name, but would their reputation stretch that far considering that a Commodore 64 with disk drive would set you back less than $500 with a bit of shopping around?

Even as they questioned the keyboard, the press’s answer to this question was an almost universal “yes.” Such was the mystique of the IBM name that they seemed to have a hard time even conceiving of the PCjr as anything but a spectacular success. Compute!, the biggest, fastest growing, and arguably most influential magazine catering to the home-computer market, was so confident that they prepared the first three issues of their second platform-specific spin-off magazine (after one for the Commodore VIC-20 and 64) before the PCjr itself was even available for purchase. Two other new magazines were also in the offing; Spinnaker, reigning kings of educational software, had a warehouse full of cartridges; Sierra On-Line had games and productivity software of their own ready to go; publishers scrambled to sign authors to write shelves full of PCjr books. When IBM kicked off the PCjr’s advertising campaign with another of their award-winning “Charlie Chaplin” television spots during Super Bowl XVIII, it attracted at least as much attention amongst the low-end crowd as Apple’s now famous 1984 advertisement for the new Macintosh which aired a few commercial breaks later. The conventional wisdom held that the PCjr couldn’t help but succeed, and few had the fortitude to buck it. Only the sober-minded Byte sounded an ominous note of caution: “Should the PCjr fail to attract a market, a lot of folks will be crushed by the resulting fall.”

A couple of months after the Super Bowl, PCjrs started shipping at last. And then… crickets. Stores that had pre-ordered dozens of units in anticipation of mad rushes and shortages watched them languish on the shelves. IBM couldn’t seem to escape their reputation as the makers of tools for big business. It turned out that many of the most interested customers were not computer neophytes looking to take the plunge for the first time, but rather businesspeople looking for something compatible with the machine on their desk at work, only smaller and cheaper, something they could use to get a bit of work done at home. They kicked the tires, but once they touched the horrid keyboard and learned that much business software — including, critically, Lotus 1-2-3 — wouldn’t run on this cut-down edition of the PC, their interest quickly faded. As for everyone else… well, they seemed perfectly happy to buy Apples and Commodores, both of which ran a hell of a lot more and better games. Compute!‘s new PCjr magazine was gone after just half a dozen issues.

Never known for giving up easily on a product, IBM bowed to the criticisms at last in the summer of 1984 and replaced the Chiclet keyboard with a proper model. In one of those moves that made IBM IBM, they offered one of the new keyboards to every single person who had already bought a PCjr. (Skeptics couldn’t help but note that, while generous, this policy wasn’t really all that expensive, since IBM had sold so few of the things in the first place.) They offered a new memory expansion that could take the machine to 256 K and, combined with the new keyboard, make it a practical possibility for the businessperson looking for a cheaper, simpler home version of her office PC. They even convinced Lotus to make a version of 1-2-3 that could run in 128 K on the PCjr. It seemed that IBM was now listening to what their potential customers said they wanted from the PCjr rather than dictating who was allowed to buy the machine and how they were allowed to use it.

Best of all, IBM started slashing the price. By the 1984 Christmas season you could buy the 128 K PCjr with floppy drive and monitor for $750. It was now very competitive with its most obvious point of comparison, the Apple II line; Consumer Reports pronounced it a “slightly better” buy than the new Apple IIc in their November issue. And — and this is the part of the PCjr story that always seems to go forgotten in articles that pronounce it “one of the biggest flops in the history of computing” or “the Edsel of the computer industry” — it actually started to sell pretty well, and had a pretty good Christmas. As the new year dawned the PCjr seemed to be gaining momentum and carving a niche for itself, even if it wasn’t quite the niche that IBM had anticipated.

It was therefore doubly surprising when IBM suddenly pulled the plug in March, cancelling the whole line with no ceremony or concrete explanation other than saying their expectations had been “overly optimistic.” It was a very un-IBM-like move from a company normally known and feared for their steady, Borg-like inexorability, their willingness to methodically iterate through failure after failure until they got a thing right — a luxury allowed them by their enormous corporate resources but denied to most of their competitors. With the Christmas sales over and the PCjr now pushing past $1000 again for a basic system, sales had once again begun to flatline. IBM apparently realized that they couldn’t make a profit on the PCjr by selling it at the only prices the market would bear. They decided the home-computer market wasn’t worth the trouble after all, not when their new $5000-plus PC/AT was again selling beyond expectations to their bread-and-butter customers in Big Business.

In an important sense, however, the PCjr didn’t die with IBM’s cancellation announcement. Radio Shack, uncertain as ever exactly what to do with their fading line of TRS-80 computers, decided in 1984 that the thing to do was to effectively give up on the Trash 80 and hitch their wagon to the IBM train. In November they released the Tandy 1000, a rather nice, robust reimagining — saying simply “clone” may be too unkind — of the PCjr that had the same graphics and sound capabilities. It became popular enough that the Tandy 1000, together with the not inconsiderable installed base of “real” PCjrs, prompted some publishers to build improved graphics and sounds into their games for these computers, thus offering some relief to an MS-DOS world that would otherwise remain a depressingly ugly place to play games for several more years.

The PCjr, then, while certainly a failure in any big-picture reckoning, wasn’t quite the hopeless case it’s so often portrayed to be. This is borne out by the sales figures, which ended up in the vicinity of 325,000 units between March 1984 and March 1985, with another 100,000 or so likely being sold during the post-cancellation fire sale. (To put those figures in perspective, consider that the admittedly much more expensive Apple Macintosh sold 275,000 units during its first year.) That said, the PCjr is significant as the first moment that IBM, who had looked infallible and inexorable from the moment they first deigned to enter the microcomputer game, got their nose bloodied. True, their ego suffered more than their bottom line; the huge profits they were continuing to rake in from their business machines dwarfed what they might have made from the PCjr even had it been a raging success. If they were going to fail somewhere, this was the place to do it. Still, this failure was a warning, or, if you like, a sign that things wouldn’t always be as easy as they had been thus far.

I’m no MBA, but the business lessons we can take away from the PCjr story seem fairly obvious. IBM ignored reasonable concerns raised when their product was still at the prototype stage, then tried to dictate to their customers rather than listen to their needs once the PCjr was on the market. They also arrogantly assumed that they could ignore their competition, that their name and reputation alone would ensure success — in other words, they took exactly the opposite approach to the one they had taken with the original IBM PC. They did, to their credit, change course eventually, but by then it was, at least in the apparent view of some powerful people in management, not worth the trouble to see the turnaround through.

Yet there is also one more element that shouldn’t go unremarked here: that of timing. Had the PCjr been introduced early in 1983 rather than 1984 its story may have been very different. While 1983 was a year of unrestrained growth and unrestrained optimism for the potential of the new home-computer industry, 1984 was a much more uncertain year, a year of failures and half-successes and uncertainty and no small amount of blowback after the ebullient promises made the previous year. The PCjr was only one part of the story of that important year. I’ll get to the rest soon. But first we have to talk about one last enduring legacy of the PCjr. We’ll do next time.

(Byte dedicated its November 1983 issue to IBM and the PC line, and explored the PCjr in depth in the March 1984 issue. Computer Entertainment published a great postmortem of the PCjr in the July 1985 issue. Also very useful were the books Hard Drive, West of Eden, and Apple Confidential. The great pictures I’ve used here are from that July 1985 Computer Entertainment.)