On January 13, 1984, Commodore held their first board of directors meeting of the year. It should have been a relaxed, happy occasion, a time to make plans for the new year but also one last chance to reflect on a stellar 1983, a year in which they had sold more computers than any two of their rivals combined and truly joined the big boys of corporate America by reaching a billion dollars in gross sales. During the last quarter of 1983 alone they had ridden a spectacular Christmas buying season to more than $50 million in profits. Commodore had won the Home Computer Wars convincingly, driving rival Texas Instruments to unconditional surrender. To make the triumph even sweeter, rival Apple had publicly announced the goal of selling a billion dollars worth of their own computers that year, only to fall just short thanks to the failure of the Lisa. Atari, meanwhile, had imploded in the wake of the videogame crash, losing more than $500 million and laying off more than 2000 workers. Commodore had just the previous summer moved into a sprawling new 585,000 square-foot, two-story headquarters in West Chester, Pennsylvania that befitted their new stature; some of the manufacturing spaces and warehouses in the place were so large that Commodore veterans insist today that they had their own weather. Yes, it should have been a happy time at Commodore. But instead there was doubt and trepidation in the air as executives filed into the boardroom on that Friday the 13th.

A day or two before, Jack Tramiel had had a heated argument with Irving Gould, Commodore’s largest shareholder and the man who controlled his purse strings, in the company’s private suite above their exhibit at the 1984 Winter Consumer Electronics Show. That in itself wasn’t unusual; these two corrupt old bulldogs had had an adversarial relationship for almost two decades now. This time, however, observers remarked that Gould was shouting as much as Tramiel. That was unusual; Gould normally sat impassively until Tramiel exhausted himself, then quietly told him which demands he was and wasn’t willing to meet. When Tramiel stormed red-faced out of the meeting and sped away in the new sports car he’d just gotten for his 55th birthday, it was clear that this was not just the usual squabbling. Now observers outside the board-of-directors meeting, which was being chaired as usual by Gould, saw him depart halfway through in a similar huff. He would never darken Commodore’s doors again.

No one who was inside that boardroom has ever revealed exactly what transpired there. With Gould and Tramiel both now dead and the other former board members either dead or aged, it’s unlikely that anyone ever will. On the face of it, it seems hard to imagine. What could cause these two men who had managed to stay together through the toughest of times, during which Commodore had more than once teetered on the edge of bankruptcy, to irrevocably split now, when their company had just enjoyed the best year in its history? We can only speculate.

Commodore had ceased truly being Tramiel’s company in 1966, when Gould swooped in to bail him out from the Financial Acceptance Scandal of the previous year. Tramiel, however, never quite got the memo. He continued to run the company like a sole proprietor to whatever extent that Gould would let him. Tramiel micro-managed to an astonishing degree. He did not, for instance, believe in budgets, considering them a “license to steal,” a guarantee that the responsible manager, knowing he had X million available, would always spend at least X million. Instead he demanded that every expenditure of greater than $1000 be approved personally by him, with the result that much of the company ground to a halt any time he took a holiday. Even as Tramiel enjoyed his best year ever in business, Gould and others in the financial community were beginning to ask the very reasonable question of whether this was really a sustainable way to run a billion-dollar company.

Still, the specific cause of Tramiel’s departure seems likely to have involved his sons. Tramiel valued family above all else, and, like a typical small businessman, dreamed of leaving “his” company to his three sons. Whether by coincidence or something else, it even worked out that each son had an area of expertise that would be critical to running a company like Commodore. Sam, the eldest, had trained in business management at York University, while Gary, the youngest, was a financial analyst with a degree from Manlow Park College and experience as a stockbroker at Merrill Lynch. Leonard, the middle child, was the intellectual and the gearhead; he was finishing a PhD in astrophysics at Columbia, and was by all accounts quite an accomplished hardware and software hacker. Sam and Gary already worked for Commodore, while Leonard planned to start as soon as he finished his PhD in a few more months. Various witnesses have claimed that Tramiel the elder now wished to begin more actively grooming this three-headed monster to take more and more of his responsibilities, and someday to take his place. Feeling nothing good could come out of such blatant nepotism inside a publicly traded corporation that was trying to put its somewhat seedy history behind it, Gould refused absolutely to countenance such a plan. Given Tramiel’s devotion to his family and his attitude toward Commodore as his personal fiefdom, it does make a degree of sense that this particular rejection might have been more than he could stomach.

In any case, Tramiel was gone, and Gould, who had made his fortune in the unglamorous world of warehousing and shipping and was reportedly both a bit jealous of Tramiel’s high profile in an exciting, emerging industry and a bit embarrassed by his gruff, untutored ways, didn’t seem particularly distraught about it. The man he brought in to replace him could hardly have been more different. Marshall F. Smith was a blandly feckless veteran of boardrooms and country clubs who had spent his career in the steel industry. It’s hard to grasp just why Gould latched onto Smith of all people. Perhaps he was following the lead of Apple, who the previous year had brought in their own leader from outside the computer industry, John Sculley. Sculley, however, understood consumer marketing, having cut his teeth at Pepsi, where he was the mastermind behind the Pepsi Challenge, still one of the most iconic and effective advertising campaigns in the long history of the Cola Wars. The anonymous world of Big Steel offered no comparable experience. Smith’s appointment was the first of a long string of well-nigh incomprehensible mistakes Gould would make over the next decade. Engineers that were initially thrilled to have proper funding and actual budgets at last were soon watching with growing concern as Smith puttered about with a growing management bureaucracy and let the company drift without direction. Many were soon muttering that it’s often better to make a decision — even the wrong decision — than to just let things hang. Whatever else you could say about Jack Tramiel, he never lacked the courage of his convictions.

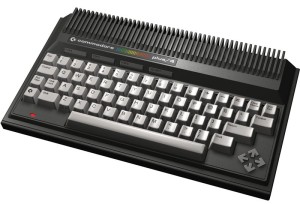

Commodore’s first significant new models, which reached stores at last in October of 1984, more than two years after the Commodore 64, hardly did much to inspire confidence in the new regime. Nothing about the Commodore 16 and the Plus/4 made any sense at all. The 16 was an ultra-low-end model with just 16 K of memory, long after the time for such a beast had passed. The trend in even inexpensive 8-bit computers was onward, toward the next magic number of 128 K, not backward to the late 1970s.

As for the Plus/4, which like the 64 was built around a variant of the 6502 CPU and had the same 64 K of memory but was nevertheless incompatible… well, it was the proverbial riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma. It was billed as a more “serious” machine than the 64, a computer for “home and business applications” rather than gaming, and priced to match at about $300, more than $100 more than the 64. It featured four applications built right into its ROM (thus the machine’s name): a file manager, a word processor, a spreadsheet, and a graphing program. All were pathetically sub-rate even by the standards of Commodore 64 applications, hardly the gold standard in business computing. The Plus/4 lacked the 64’s sprites and SID sound chip, which made a degree of sense; for a dismaying number of years yet a lack of audiovisual capability would be taken as a signifier of serious intent in computing. But why did it offer more colors, 128 as opposed to the 64’s 16? And as an allegedly more serious computer, why didn’t it offer the 80-column display absolutely essential for comfortable word processing and other typical productive tasks? And as a more serious (and expensive) computer, why did it have a rubbery keyboard almost as awful to type on as the IBM PCjr’s Chiclet model? And would all those serious, more productive buyers really be doing a lot of BASIC programming? If not, why was one of the main selling points a much better BASIC than the bare-bones edition found in the 64? Info, a magazine that would soon build a reputation for saying the things about Commodore’s bizarre decisions that nobody else would, gave the Plus/4 a withering review:

The biggest problem with the Plus/4 is the fundamental concept: an 8-bit, 64 K, 40-column desktop personal computer. Commodore already makes the best 8-bit, 64 K, 40-column desktop personal computer you can buy, with literally thousands of products supporting it! Why should consumers want a “new” machine with no significant advances, several new limitations, and virtually no third-party product support? And why would a company with no competition in the under-$500 category bring out an incompatible [machine] that can’t compete with anybody’s machine except their own? It just doesn’t compute!

Info ran a wonderfully snarky contest in the same issue, giving away the Plus/4 they’d just reviewed. After all, it was “sure to become a collector’s item!” Even the more staid Compute!’s Gazette managed to flummox a poor Commodore representative with a single question: “Why buy a 264 [a pre-release name for the Plus/4] instead of a 64 that has a word processor and, say, a Simon’s BASIC? It would be the equivalent of the 264 for less money.” Commodore happily claimed that the Plus/4 had enough utility built right in for the “average small business” (maybe they meant one of the vast majority that fail within a year or two anyway), but in reality it seemed like it had been cobbled together from spare parts that Commodore happened to have lying around. In fact, that’s not far from what happened — and Tramiel actually bears as much responsibility for the whole fiasco as the clueless Marshall Smith.

Tramiel, you’ll remember, had driven away the heart of his engineering team in his usual hail of recriminations and lawsuits shortly after they had created the 64 for him. He did eventually find more talented young engineers, notably Bil Herd and Dave Haynie. (Commodore always preferred their engineers young and inexperienced because that way they didn’t have to pay them much — a strategy that sometimes backfired but was sometimes perversely successful, netting them brilliant, unconventional minds who would have been overlooked by other companies.) When Herd arrived at Commodore in early 1983, engineers had been tinkering for some time with a new video and audio chip, the TED (short for Text Display). With engineering straitened as ever by Tramiel’s aversion to spending money, the 23-year-old Herd soon found himself leading a project to make the TED the heart of a new computer, despite the fact that it was in some ways a step back, lacking the sprites of the 64’s VIC chip and the marvelous sound capabilities of its SID chip. Marketing came up with the dubious idea of including applications in ROM, which by all accounts delighted Tramiel.

Tramiel, who at some fundamental level still thought of the computers he now sold like the calculators he once had, failed to grasp that the whole value of a computer is the ability to do lots of different things with it, to have lots and lots of options its designers may never have anticipated, all through the magic of software. Locking applications into ROM, making them impossible to replace or update, was kind of missing the point of building a computer in the first place. Failing to understand that a computer is only as good to consumers as the quality and variety of its available software, Tramiel also saw no problem with making the new machine incompatible with the 64. It seems to have come as a complete surprise to him when the machine was announced at that fateful Winter CES and everyone’s first question was whether they could use it to run the Commodore 64 software they already had.

After Tramiel’s abrupt departure, Commodore pushed ahead with the 16 and Plus/4 in the muddled way that would be their wont for the rest of the company’s life, despite a skeptical press and utterly indifferent consumers. It all made so little sense that some have darkly hinted of a conspiracy hatched by Tramiel amongst his remaining loyalists at Commodore to get the company to waste resources, time, and credibility on these obvious losers. (Tramiel recruited a substantial number of said loyalists to join him after he purchased Atari and got back in the home-computer game — exactly the sort of thing for which he so often sued others. But that’s a story for a later article.) Incredibly given the cobbled nature of the machine, it took nine more months after that CES to finally get the 16 and Plus/4 into production and watch them duly flop. Again, such a glacial pace would prove to be a consistent trait of the post-Tramiel Commodore.

By the time they did appear at last, the poor, benighted 16 and Plus/4 had more working against them than just their own failings, considerable as those may have been. The year as a whole was marked by failures in the home-computer segment of the market. Atari was reeling. Coleco was taking massive losses on their tardy entry into the home-computing field, the Adam. And of course I’ve already told you about the IBM PCjr.

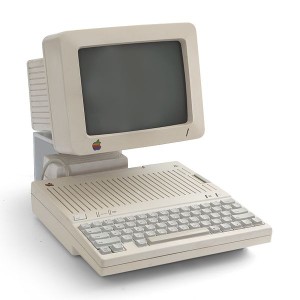

Even Apple, who had enjoyed a splashy, successful launch of their new higher-end Macintosh (another story for a later date), had a somewhat disappointing new model amongst their bread-and-butter Apple II line. The “c” in the Apple IIc’s name stood for “compact,” and it was indeed a much smaller version of Steve Wozniak’s old evergreen design. Like the Macintosh, it was a closed system designed for the end user who just wanted to get work (or play) done, not for the hackers who had adored the earlier editions of the II with their big cases and heaps of inviting expansion slots. The idea was that you would get everything you, the ordinary user, really needed built right in: all of the fundamental interface cards, a disk drive, a full 128 K of memory (as much as the Macintosh), etc. All you would really need to add to have a nice home-office setup was a monitor and a printer.

But the IIc was not envisioned just as a more practical machine: as the only II model after the first with which Steve Jobs played an important role, it evinced all of his famous obsession with design. Indeed, much of the external look and sensibility that we associate with Apple today begins as much here as with the just slightly older — and, truth be told, just slightly clunkier-looking — first Macintosh model. The Apple IIc was the first product of what would turn into a longstanding partnership with the German firm Frog Design. It marks the debut of what Apple referred to as the “Snow White” design language — slim, modern, sleek, and, yes, white. Everything about the IIc, including the packaging and the glossy manuals inside, oozed the same chic elegance.

Apple introduced the IIc at a lavish party and exhibition in San Francisco’s Moscone Center in April of 1984, just three months after a similar shindig to launch the Macintosh. The name was chosen to mollify restless Apple II owners who feared — rightly so, as it would turn out; even at “Apple II Forever” Jobs made time for a presentation on “The First 100 Days of Macintosh” — that Sculley, Jobs, and their associates had little further interest in them. Geniuses that they have always been for burnishing their own myths, Apple built a museum right there in the conference center, its centerpiece a replica of the garage where it had all begun. The IIc unveiling itself was an audiovisual extravaganza featuring three huge projection screens for the music video Apple had commissioned for the occasion. The most dramatic and theatrical moment came when Sculley held the tiny machine above him onstage for the first time. As the crowd strained to see, he asked if they’d like a closer look. Then the house lights suddenly came up and every fifth person in the audience stood up with an Apple IIc of her own to show and pass around.

Apple confidently predicted that they would soon be selling 100,000 IIcs every month on the strength of the launch buzz and a $15 million advertising campaign. In actuality the machine averaged just 100,000 sales per year over its four years in Apple’s product catalogs. The old, ugly IIe outsold its fairer sibling handily. This left Apple in a huge bind for a while, for they had all but stopped production of the IIe in anticipation of the IIc’s success while wildly overproducing IIcs for a rush that never materialized. Thus for some time stores were glutted with the IIcs that consumers didn’t want and couldn’t get their hands on the IIes that they did. (It’s interesting to consider that the PCjr almost certainly sold more units than the IIc, which has never been tarred with the label of outright flop, during each machine’s first year on the market. Narratives can be funny things.)

It remains even today somewhat unclear why the world never embraced the IIc as it had the three Apple II models that preceded it. There’s some evidence to suggest that consumers, not yet conditioned to expect each new generation of computing technology to be both smaller and more powerful than the previous, took the IIc’s small size to be a sign that it was not as serious or powerful as the IIe. Apple was actually aware of this danger before the IIc debuted. Thus the advertising campaign worked hard to explain that the IIc was more powerful than its size would imply, with the tagline, “Announcing a technological breakthrough of incredible proportions.” Yet it’s doubtful whether this message really got through. In addition, the IIc was, like the PCjr, an expensive proposition for the home-computer buyer: almost $1300, $300 more than a basic IIe. For that price you got twice the memory of the IIe as well as various other IIe add-on options built right in, but the value of all this may have been difficult for the novice buyer, the IIc’s main target, to grasp. She may just have seen that she was being asked to pay more for a smaller and thus presumably less capable machine, and gone with the bigger, more serious-looking IIe (if anything from Apple).

Then again, maybe the IIc was just born under a bad sign. As I’ve already noted, nobody was having much luck with their new home computers in 1984, almost regardless of their individual strengths and weaknesses.

But why was this trend so universal? That’s what people inside the industry and computer evangelists outside it were asking themselves with increasing urgency as the year wore on. As 1984 drew toward a close, the inertia began to affect even the most established warhorses, the Commodore 64 and the Apple IIe. Both Commodore and Apple posted disappointing Christmas numbers, down at least 20% from the year before, and poor Commodore, now effectively a one-product company completely reliant on continuing sales of the 64, sank back well below that magic billion-dollar threshold again. In the grand scheme of things the Commodore 64 was still a ridiculously successful machine, by far the bestselling computer in the world and the preeminent gaming platform of its era. Yet there increasingly seemed to be something wrong with the home-computer revolution as a whole.

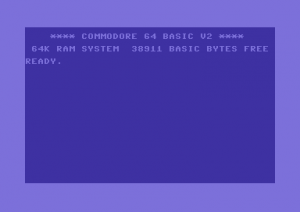

The fact was that a backlash had been steadily building almost from the moment that the spectacular Christmas 1983 buying season had ended. Consumers had begun to say, and not without considerable justification, that home computers promised far more than they delivered. Watching all those bright, happy faces in television and print advertising, people had bought computers expecting them to do the things that the computers there were doing. As Commodore’s advertising put it, “If you’re not pleased with what’s on your TV set tonight, simply turn on your Commodore 64.” Yet what did you get when you turned on your 64 — after you figured out how to connect it to your TV in the first place, that is? No bright fun, just something about 38,911 somethings, a READY prompt, and a cryptically blinking cursor. Everything about television was easy; everything about computers was hard. Computers had been sold to consumers like any other piece of consumer electronics, but they were not like any other piece of consumer electronics. For the vast majority of people — those who had no intrinsic fascination with the technology itself, who merely wanted to do the sorts of things those families on TV were doing — they were stubborn, frustrating, well-nigh intractable things. Ordinary consumers were dutifully buying computers, but computers were at some fundamental level not yet ready for ordinary consumers.

The computer industry was still unable to really answer the question which had dogged and thwarted it ever since Radio Shack had run the first ads showing a happy housewife sorting her recipes on a TRS-80 perched on the kitchen table: why do I, the ordinary man or woman with children to feed and a job to keep, need one? Commodore had cemented the industry’s go-to rhetoric with the help of William Shatner in their VIC-20 advertising campaign that first carved out a real market segment for home computers. You needed a computer for productivity tasks and for your children’s future, “Johnny can’t read BASIC” having replaced “Johnny can’t read” as the marker of a neglectful parent. Entertainment was relegated to an asterisk at the end: “Plays great games too!”

Yet, honestly, how productive could you really be with even the Commodore 64, much less the 5 K VIC-20? Some people did manage to do productive things with their 64s, but most of those who did forgot or decided not to ask themselves a simple question: is doing this on the computer really easier than the alternative? The answer was almost always no. Hobbyists chose to do things on the computer because it was cool, not because it was practical. Never mind if it took far more effort to keep one’s address book on the Commodore 64, what with its slow disk drive and quirky, unrefined software, than it would have to just have a paper card file. Never mind if it was much riskier as well, prone to deletion by an errant key swipe or a misbehaving disk drive. It was cooler, and that was all that mattered — to a technology buff. Most other people found it easier to address their Christmas cards by hand than to try to feed envelopes through a tractor-fed dot-matrix printer that made enough noise to wake the neighbors.

Perhaps the one possible compelling productive use of a machine like the Commodore 64 in the home was as a word processor. Kids today can’t imagine how students once despaired when their teachers told them that a report had to be typed back in the era of typewriters, can’t conceive how difficult it was to get anything on paper in typewritten form when every mistake made by untutored fingers meant trying to decide between pulling out the Liquid Paper or just starting all over again. But even word processing on the 64 was made so painful by the 40-column screen and manifold other compromises that there was room to debate whether the cure was worse than the disease. Specialized hardware-based word processors became hugely popular during this era for just this reason. These single-function, all-in-one devices were much more pleasant to use than a Commodore 64 equipped with a $30 program, and cheaper than buying a whole computer system, especially if you went with a higher priced and thus more productively useful model like the Apple II.

The idea that every child in America needed to learn to program, lest she be left behind to flip burgers while her friends had brilliant careers, was also absurd on the face of it. It was akin to declaring during the days of the Model T that every citizen needed to learn to strip down and rebuild one of these newfangled automobiles. Basic computer literacy was important (and remains so today); BASIC literacy was not. What a child really needed to know could largely be taught in school. Parents needn’t have fretted if Junior preferred reading, listening to music, playing sports, or practicing origami to learning the vagaries of PEEKs and POKEs in BASIC 2.0. There would be time enough for computing when computing and Junior had both grown up a bit.

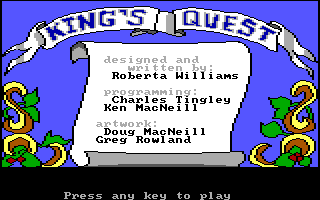

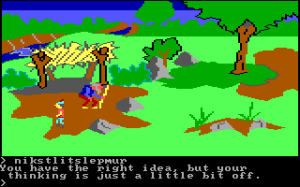

So, everything had changed yet nothing had changed since the halcyon days of the trinity of 1977. Computers were transforming the face and in some cases the very nature of business, yet there remained just two compelling reasons to have one in the home: 1) for the sheer joy of hacking or 2) for playing games. Lots more computers were now being used for the latter than the former, thanks to the vastly more and vastly better games that were now available. But for many folks games just weren’t a compelling enough reason to own one. The Puritan ethic that makes people feel guilty of their pleasures was as strong in America then as it remains today. It certainly didn’t help that the media had been filled for several years now with hand-wringing about the effect videogames were having on the psyches of youngsters. (This prompted many computer publishers of this period to work hard, albeit likely with limited success, to label their computer games as something different, something more cerebral and rewarding and even, dare we say it, educational than their simplistic videogame cousins.)

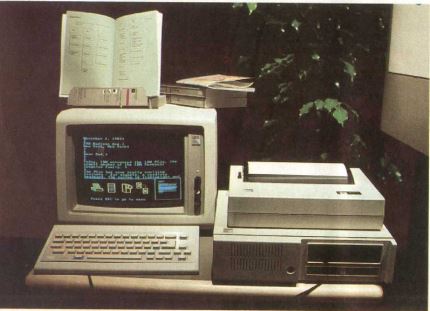

But, perhaps most of all, computers still remained quite expensive when you really dug into everything you needed for a workable system. Yes, you could get a Commodore 64 for less than $200 by the Christmas of 1983. But then you needed a disk drive ($220) if you wanted to do, well, much of anything with it; a monitor ($220) if you wanted a nice picture and didn’t want to tie up the family television all the time; a printer ($290) for word processing, if you wanted to take that fraught plunge; a modem ($60) to go online. It didn’t take long until you were approaching four digits, and that’s without even entering into a discussion of software. There was thus a certain note of false advertising in that sub-$200 Commodore 64. And because these machines were being sold through mass merchandisers rather than dealers, there was no one who really knew better, who could help buyers to put a proper system together at the point of sale. Consumers, conditioned by pretty much everything else that was sold to them not to expect the 64 on its own to be pretty much useless, were often baffled and frustrated when they realized they had bought an expensive doorstop. Many of the computers sold during that Christmas of 1983 were turned on a few times only, then consigned to the back of the closet or attic to gather dust. The bad taste they put in many people’s mouths would take years to go away. Meanwhile the more complete, useful machines, like the Apple IIc and the PCjr, were still more expensive than a complete Commodore 64 system — and the games on them weren’t as good to boot. Hackers and passionate gamers (or, perhaps more commonly, their generous parents) were willing to pay the price. Curious novices largely were not. Faced with no really good all-purpose options, many — most, actually — soon decided home computers just weren’t worth it. The real home-computer revolution, as it turned out, was still almost ten years away. About 15% of American homes had computers — at least ostensibly; many of them were, as just mentioned, buried in closets — by January 1, 1985, but that figure would rise with agonizing slowness for the rest of the decade. People could still live perfectly happy lives fully plugged into the cultural discourse around them and raise healthy, productive children in the process without owning a computer. Only much later, with the arrival of the World Wide Web and computers equipped with more intuitive graphical user interfaces for accessing it, would that change.

Which is not to say that the software and information industries that had exploded in and around the home-computer revolution during 1982 and 1983 died just like that. Many of its prominent members, however, did, as the financial gambles they had taken in anticipation of the home-computer revolution came back to haunt them. We’ve just seen how Sierra nearly went under during this period. Muse Software and Scott Adams’s Adventure International, to name two other old friends from this blog, weren’t so lucky; both folded in 1985. Electronic Arts survived, but steered their rhetoric and choice of titles somewhat away from Trip Hawkins’s original vision of “consumer software” toward titles tilted more toward the hardcore, in proven hardcore genres like the CRPG and the adventure game.

Magazines were even harder hit. By early 1984 there were more than 300 professionally published computing periodicals of one sort or another, many of them just founded during the boom of the previous year. Well over half of these died during 1984 and 1985. Mixed in with the dead Johnny-come-latelys were some cherished veteran voices, among them pioneers Creative Computing (1974), SoftSide (1978), and Softalk (1980). The latter’s demise, after exactly four years and 48 issues of sometimes superb people-focused journalism, came as a particular blow to the Apple II community; Apple historian Steven Weyhrich names this moment as nothing less than the end of the “golden age” of the Apple II. Those magazines that survived often did so in dramatically shrunken form. Compute!, for instance, went from 392 pages in December of 1983 to 160 ten months later.

Yet it wasn’t all doom and gloom. Paradoxically, some software publishers still did quite well. Infocom, for example, had the best single year in their history in 1984 in terms of unit sales, selling almost 750,000 games. It seemed that, with more options than ever before, software buyers were becoming much more discerning. Those publishers like Infocom who could offer them fresh, quality products showing a distinctive sensibility could do very well. Those who could not, like Adventure International with their tired old two-word parsers and simplistic engines, suffered the consequences. That real or implied asterisk (“Plays great games too!”) at the end of the advertising copy remained the great guilty secret of the remaining home-computer industry, the real reason computers were in homes at all. Thankfully, the best games were getting ever more complex and compelling; otherwise the industry may have been in even more trouble than it actually was.

Indeed, with a staggering number of machines already out there and heaps still to be sold for years to come, the golden age for Commodore 64 users was just beginning. This year of chaos and uncertainty was the year that the 64 really came into its own as a games machine, as programmers came to understand how to make it sing. Companies who found these keyboard maestros would be able to make millions from them. The home-computer revolution may not have quite panned out as anticipated and the parent company may have looked increasingly clueless, but for gamers the Commodore 64 stood alone with its combination of audiovisual capability, its large and ever growing catalog of games, and its low price. What with game consoles effectively dead in the wake of Atari’s crash and burn, all the action was right here.

In that spirit, we’ll look next time at the strange transformation that led one of our stodgiest old friends from earlier articles to become the hip purveyor of some of the slickest games that would ever grace the 64.

(The indispensable resources on Commodore’s history remain Brian Bagnall’s On the Edge and its revised edition, Commodore: A Company on the Edge. Frank Rose’s West of Eden is the best chronicle I know of this period of Apple’s history. The editorial pages and columnists in Compute! and Compute!’s Gazette provided a great unfolding account of a chaotic year in home computing as it happened. Particular props must go to Fred D’Ignazio for pointing out all of the problems with the standard rhetoric of the home-computer revolution in Compute!‘s May 1984 issue — but he does lose points for naming the PCjr as the answer to all these woes in the next issue.)