There’s a lot of interesting stuff to talk about in Ultima III, to the extent that I wasn’t quite sure how to wedge it all into a conventional review. So I decided to try this approach, to balance my usual telling with quite a bit of showing. Or something like that. Anyway, I found it fun to do.

If you’re inspired to play Ultima III yourself, know that Good Old Games is selling it in a collection which also contains Ultima I and II. Less legitimately, there are the usual abandonware sites and ROM collections where you can find the original Apple II version that I play here, but you’re on your own there. Some spoilers do follow, although Ultima III is tricky enough that you may just welcome whatever little bit of guidance you glean from this post.

Garriott was really proud of his game’s subtitle, Exodus, to the extent that in the game itself and most early advertising it’s actually more prominent than the Ultima name. He draws no connection to its meaning as an English noun or to the Bible. It’s simply a cool-sounding word that he takes as the name of his latest evil wizard, the love child of his two previous evil wizards, Mondain from Ultima I and Minax from Ultima II. Roe R. Adams III did make a somewhat strained attempt to draw a connection to the expected implications of the word in the manual via a recasting of an old seafaring mystery:

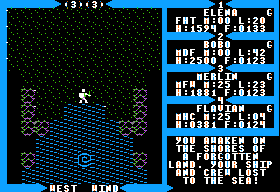

One possible clue as to the identity of thy nemesis has been discovered. A derelict merchant ship was recently towed into port. No crewmen were aboard, alive or dead. Everyone had vanished, as if plucked by some evil force off the boat. The only thing found was a word written in blood on the deck: EXODUS.

I never hear anything about this ghost ship in the game itself. Also left unexplained, as it was in Ultima II, is why Mondain was on Garriott’s fantasy world of Sosaria and Minax was on our own Earth. This time I’m stuck back on Sosaria again. Garriott would finally get more serious about making an Ultima mythos that makes some kind of sense with the next game, but for now… let’s just say I won’t be spending much more time discussing the plotting or the worldbuilding.

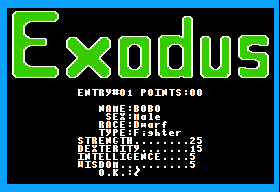

In Ultima III I get to create and control a full party of four adventurers rather than a single avatar. This is actually the only Ultima that works quite this way. Later games would use the code Garriott first developed here to allow players to have more than one person in their parties, but would start them off with a single avatar. Finding other adventurers in the game world itself and convincing them to join would become part of the experience of play and an important component of those games’ much richer plots.

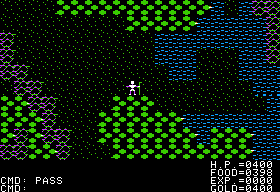

With my party created, I’m dumped into Sosaria, right outside the town of Britain and the castle of Lord British in what has already become by Ultima III a time-honored tradition.

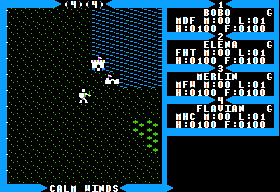

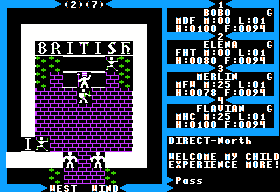

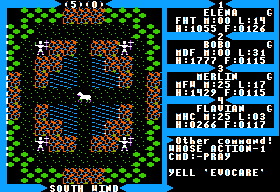

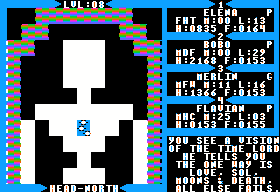

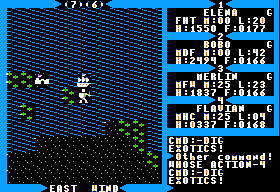

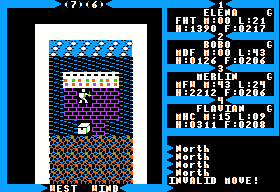

One of the fascinating aspects of playing through the Ultima games in order is seeing which pieces are reused from earlier games and which are replaced. Programming often really is a game of interchangeable parts. On the left above is Ultima II, on the right Ultima III. The same old tile engine that dates back to Ultima I is still in place in both games, but Ultima III changes the screen layout considerably and makes everything a bit more attractive and ornate within the considerable limitations of the Apple II. It no longer uses the Apple II’s mixed display mode that displays text rather than graphics on the bottom four lines of the screen. Instead the whole screen is now given over to a graphics display, with a character generator, once an exotic piece of technology but by 1983 commonplace, used to put words anywhere on the screen.

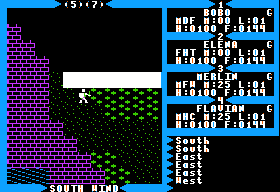

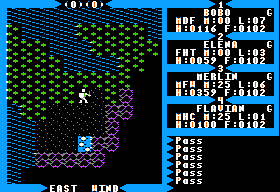

When I enter a town for the first time another of Ultima III‘s additions to the old tile-graphics engine becomes clear: a line-of-sight algorithm now prevents me from seeing through walls. This adds an extra dimension of realism, but proves to be a mixed blessing. We’ll talk about why that is in just a little bit.

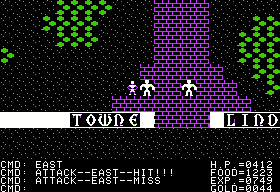

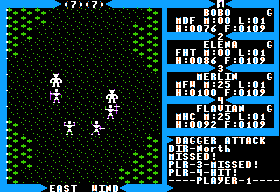

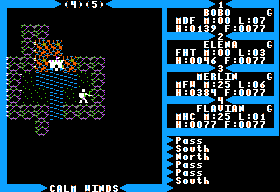

And when I run into a couple of wandering orcs for the first time I see another big addition: a separate strategic-combat screen that pops up when a fight begins. You can see that on the right above; the old Ultima II system of flailing in place on the map screen is on the left. The earlier system would obviously be unworkable with a party of four. Unlike with Wizardry, combat has never been the heart of Ultima‘s appeal, but that doesn’t mean you don’t spend a lot of time — maybe too much time — in Ultima III engaging in it. The new system does add some welcome interest to the old formula. I can now move each character about individually, use missile weapons (a highly recommended strategy that lets me take out many monsters before they can get close enough to damage me), and cast quite a variety of offensive and defensive spells. Less wonderfully, all those random encounters with orcs and cutthroats now take much more time to resolve, which is one of the things that can turn Ultima III into quite the slog by the time all is said and done. Also contributing to the tedium: in a harbinger of certain modern CRPGs, random encounters are balanced to suit the general potency of my party, thus guaranteeing that they will still take some time even once I have quite a powerful group of characters.

As part of a general tightening of the game’s mechanics likely prompted by unfavorable comparisons of previous Ultimas to previous Wizardries, the strange system of hit points as a commodity purchasable from Lord British has finally been overhauled. Now healing works as you might expect: each character has a maximum number of hit points which Lord British raises by 100 every time I visit him after gaining a level. Alas, this works only until level 25 and 2500 hit points. At least I don’t have to pay him for his trouble anymore. In the screenshot above his “Experience more!” means that I haven’t yet gained a level for him to boost my hit-point total; small wonder, as all my characters are still level 1.

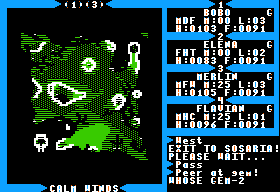

Having gotten the initial lay of the land, I settle into the rhythm of building my characters, exploring the world map, and talking to everyone I can find in the towns. The latter process, like so much in Ultima III, is equal parts frustrating and gratifying. The good citizens of Sosaria insist on speaking in the most cryptic of riddles. And here we see the darker side of Garriott’s new line-of-sight system: most of the most vital clue-givers are tucked away in the most obscure possible corners of the towns, like the fellow shown in the screenshot above and left. I have to scour every town square by tedious square to be absolutely certain I haven’t missed a vital clue, a vital link in a chain of tasks required to win that is much more complicated than those found in the earlier games. On the other hand, the gratification that comes when another piece of the puzzle falls into place is considerable. Ultima has always been better at delivering that thrill of exploration than just about any other CRPG.

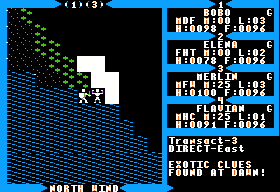

There are in many places in Ultima III some small kindnesses, some elements that, once I figure out how they work, can make things easier. In the screenshot to the right I’m using a magic gem, purchasable from thieves guilds in a couple of the towns, to get a bird’s-eye view of the town I’m currently in. Ferreting out these secrets and hidden mechanics contributes to another thing Ultima always does well: making you feel smart.

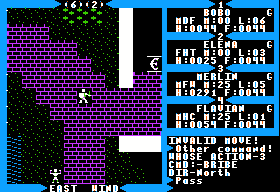

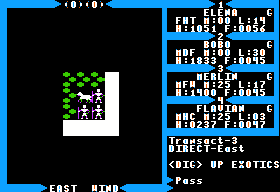

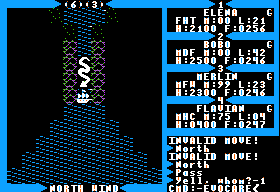

Still, it’s possible to take this whole discovery thing too far. In one of the more astonishing design decisions in Ultima III, Garriott has consciously engineered into his hotkey-driven interface an element of guess the verb. After all, why should text adventurers have all the fun? There’s a mysterious OTHER command this time, which lets me enter new verbs. Divining what these are depends on my sussing that words surrounded by “<>” in characters’ speech refer to new verbs. (“<SEARCH> the shrines.”) A very strange design choice, which does a good job of illustrating the gulf in player expectations between now and then, when guess the verb was still trumpeted by many as an essential element of adventure games rather than just a byproduct of their technical limitations. Given that, why not try to engineer it into Ultima, a series which always tried to offer more, more, more? Thankfully, it would disappear again from Ultima IV, in what could be read as another reflection of changing player expectations.

In the screenshot at left above I’ve just used the hidden verb “BRIBE” to convince a guard who just a second before was standing right next to me to go away for the modest fee of 100 gold. Now I can go into the shop and steal with relative impunity. (Ultima III is, as we’ll continue to see, very much an amoral world, the last Ultima about which that can be said.) Bribing is only useful; other hidden verbs are vital.

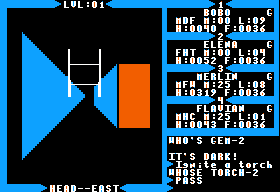

For instance, the second screenshot above shows me gathering a piece of important information using the hidden verb “PRAY” inside a temple. This is actually quite an interesting sequence. PRAYing yields the information that I must YELL — YELL being one of the standard hotkey-based commands — “EVOCARE” at a certain place. It’s perilously close to two guess-the-verb — or at least guess-the-word — puzzles joined together.

We see an interesting re-purposing of previous Ultima technology in the form of the eight moon gates which wink in and out of existence in a set pattern on the world map. In Ultima II, you may recall, these supposedly allowed me to travel through time, although effectively they just provided access to different world maps; nothing I did in one time could have any direct effect on any of the others. Here they’re renamed and used more honestly, as ways to move quickly from place to place on the primary world map. (There are only two world maps this time, the primary one and an alternate world called Ambrosia which we’ll get to shortly.) They also allow me to reach a few places that are otherwise completely inaccessible, as the screenshot at right above illustrates. Well, okay… I could also get there with a ship, an element we’ll talk about later. But that’s not always the case; there’s at least one vital location that can be visited only via moon gate. Thus understanding the logic of the moon gates and charting their patterns is another critical aspect of cracking the puzzle of Ultima III. Moon gates would continue to be a fixture in the Ultimas to come.

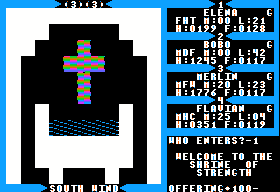

Garriott had completely rewritten his dungeon-delving engine for Ultima II, replacing what had been the slowest and most painful part of Ultima I with a snappy new piece that replaced a wire-frame portrait of the surroundings with glorious filled-in color. It’s easily the most impressive and appreciated improvement in that game. But then, like so much else in Ultima II, he squandered it by giving his players no reason to go there. Thus Ultima III almost feels like the new dungeon engine’s real debut. Not only can I harvest a lot of desperately needed gold from the dungeons, but I must also explore them to find five vital “marks” that give special abilities which are in turn key to solving the game. And at the bottom of the Dungeon of Time I meet the Time Lord. (Garriott’s Time Bandits fixation had apparently not yet completely run its course — or are we now dealing with a Doctor Who obsession?) He gives a portentous clue that will be vital to the end-game.

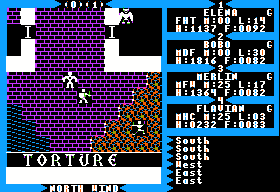

Sosaria is still a world where might makes right. Lord British, the supposedly benevolent monarch, has a dirty little secret, an ugly torture chamber hidden in the depths of his castle. It’s almost enough to make you ask who’s really the evil one here. The manual talks a good game about Exodus, but he doesn’t actually do anything at all in the game itself, just hangs out in his castle and waits for us to come kill him. Meanwhile Lord British has torture chambers, and his lands are beset with monsters trying to kill me, and he seems completely disinterested in helping me beyond boosting my hit points from time to time. Nor am I exactly morally pure: my own mission in the torture chamber is not to save the fellow who’s been thrown into a lake of fire, merely to extract some information from him.

The screenshot at the right shows an even more morally questionable episode, albeit one that requires a bit more explanation. I’m the one on the horse. Each of the three clerics next to me has a critical clue to convey. However, I can’t interact on a diagonal, meaning that the one at bottom right is inaccessible to me — unless I open up a lane by killing one of his companions in cold blood, that is. I want to emphasize here that the clue the inaccessible cleric has to offer is absolutely necessary; he tells where to dig for some special weapons and armor that provide the only realistic way to survive the end-game in Exodus’s castle. Thus the only way forward is, literally, murder, and it’s a conscious design choice on Garriott’s part. Of course, he didn’t think of it quite that way. He just saw it as an interesting mechanic for a puzzle, having not yet made the leap himself from mechanics to experiential fiction. Again, all of that would change with Ultima IV.

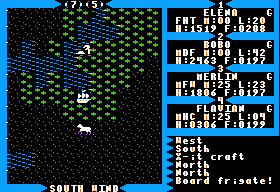

Speaking of horses: given Garriott’s newfound willingness to edit, the vehicles available to me in Ultima III are neither so plentiful nor so outrageous as they were in Ultima II. The ridiculous and ridiculously cool airplane, for instance, is gone.

I can buy horses for my party in a couple of towns. These let me move overland a bit faster, using less food and avoiding many of the wandering monsters and the endless combats they bring which can test the patience of the hardiest of players. A ship can be acquired only by taking it from one of the roving bands of pirates that haunt the coastline. There aren’t actually a lot of pirates about, which can get very frustrating; a ship is required to visit several important areas of the game, and finding one can be tough. In the right-hand screenshot above I’ve sailed to an island, where, following the lead of the cleric whose companion I killed in cold blood, I’ve dug up the aforementioned special weapons that are required to harm Exodus’s innermost circle of minions.

I also need a ship to get to the alternate world of Ambrosia, which I can manage only by the counter-intuitive step of sailing into a whirlpool. Here I find shrines to each of the four abilities, the only ways to raise my scores above their starting values. Doing so is vital; in Ultima III‘s still somewhat strange system, ability scores have much more effect on my performance in combat and other situations than my character level. For instance, the number and power of spells I can cast has nothing to do with my level, only with my intelligence (wizard spells) or wisdom (cleric spells).

The explicitly Christian imagery in these shrines, and occasionally in other places in the game, is worth noting. It’s doubtless a somewhat thoughtless result of Garriott’s SCA activities and his accompanying fascination with real medieval culture, but it could certainly be read as disrespectful, a trivializing of religious belief. It’s the sort of thing that TSR, creators of Dungeons and Dragons, were always smart enough to stay well away from (not that it always helped them to avoid controversy). Similarly, you definitely will never see crosses in a big-budget modern fantasy CRPG.

Ready at last, I piece together a string of clues and sail to the “Silver Snake”. There I yell the password “EVOCARE” to enter Exodus’s private grotto. The Silver Snake itself provides a good illustration of just how intertwined the early Ultima games were with Garriott’s own life. And the anecdote that explains its presence here also shows some of the difficulties of trying to pin down the facts about Garriott’s life and career.

Growing up in Houston in the mid-1970s, Garriott was one of the few people to see the infamously awful adventure film Doc Savage: The Man of Bronze. Members of the lost Central American tribe that Savage battles in the movie all bear a tattoo on their chest of the Mayan god Kulkulkan, about whom little is known today apart from his symbol: a serpent.

Young Richard thought the symbol so cool-looking that he went to his mother’s silversmithing workshop in that room above his family’s garage that would one day house Origin Systems and made the design — or as close an approximation as he could manage — for himself. He put his new amulet on a chain made from one of his mother’s belts. He told Shay Addams about it circa 1990:

“And this chain now resides around my neck 365 days a year, 24 hours a day — it has essentially remained there for the rest of my life ever since the day I put it on. There is no way to remove it without taking a screwdriver to it and prying open one of the links. For the first couple of years that I wore it, I actually had a link that I used to open and close a little bit. After I realized I was wearing out something by doing that, I quit doing it, so this necklace has remained here ever since. It literally never comes off. The chain was gold-colored when I first put it on. As it wears off, the colors keep changing, and now it rusts on my neck. I mean literally, every day. When I go, I may die of rust poisoning or something.”

Shortly after finishing Ultima III, Garriott loaned the original to his father Owen to carry with him on his second and final trip into space. It went into space again with Richard himself in 2008, and it seems that he still wears it frequently if not constantly. For what it’s worth, the color now seems to be a dull silver, almost a pewter shade.

But… wait. A close look at the early portrait of Origin Systems I published earlier shows that he doesn’t seem to be wearing it there, although Ken Arnold is using either the original or a duplicate as a key ring. Various other contemporary photos show no evidence of a chain or amulet, at least not of the construction and bulk of the one he wears to public appearances in recent years. Now, you could say that to even question this is petty, and in a very real sense you’d be right. Really what does it matter whether he never takes the serpent medallion off or whether it’s merely a precious link to his past that he wears on special occasions? I mention it here only because it points to how slippery everything involving Garriott can be, how much the man often seems to prefer SCA-style legend over the messier world of historical facts, and by extension how eager his interviewers and chroniclers often are to mythologize rather than document. That in turn forces me to spend far more time than I’d like to debunking or at least double-checking everything he says and much of what is said about him. But we’ve moved far afield from Ultima III now, so enough beating of this particular dead horse.

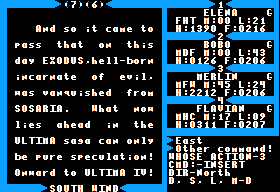

As I’ve mentioned before, Garriott excised most of the anachronistic science-fiction elements from Ultima III to focus on fantasy. But notice that I said “most.” When I get to the grand climax at last, I learn that Exodus apparently is in fact… a giant deranged computer in the tradition of Star Trek. The four magic cards I quested for were apparently punched cards — Exodus is an old-fashioned evil computer — that I need to use to shut him down or change his programming or… something. Of course, none of this make a lick of sense — how did Mondain and Minax manage to breed a computer child? But I dutifully insert the cards and shut him down, and am left to “speculation” about Ultima IV.

In that spirit, let’s note that Garriott himself sees the Ultimas through Ultima III as essentially technical exercises, written “to satisfy my personal interest in seeing how much better a game I could put together with the skills I’d acquired while creating the previous game.” While his technology would continue to improve, with Ultima III it reached a certain point of fruition at which it was capable of delivering more than an exercise in rote mechanics, was capable of sustaining real experiential fictions. Garriott didn’t entirely realize that at the time he was writing Ultima III, and thus the game takes only the most modest of steps in that direction. When he started on the next one, however, it would all come home. In a way, it’s with that game that Ultima really became Ultima as we remember it today. We have much else to talk about before we get there, but I hope you’ll still be around when we do. With Ultima III Garriott had his foundation in place. Next would come the cathedral.