Fair warning: this post spoils Planetfall thoroughly and aggressively. If you want to play it unspoiled, do so now. (Yes, it’s worth playing.) Then come back here.

A hapless lone spacefarer — that’s you — comes upon an aged but now decaying alien artifact. You must ferret out its secrets, discover what it is and how it was meant to work, and finally repair its systems. When you succeed completely in this last the original inhabitants, who were only sleeping as they hoped and waited for someone like you to come along, are revived. You are rewarded for your efforts with fame and fortune on your home planet and beyond, along with the satisfaction of having completed another Infocom game.

Sounds like an Infocom game we’ve already looked at, doesn’t it? Stripped down to basics, it’s rather amazing how similar the plot of Infocom’s eighth release, Planetfall, is to that of their fifth, Starcross. Based upon my summary, one might ask whether Infocom was already running out of ideas. Yet few who have played both games have ever asked that question because when you’re actually playing them the two games could hardly feel more different. Planetfall, you see, marks the arrival of Steve Meretzky, who if (arguably) not Infocom’s best author was certainly the one with the most immediately distinctive voice and design sensibility. He would have a huge influence not only on Infocom’s subsequent works but on adventure gaming in general, an influence that persists to this day. For better (sometimes) or for worse (probably more often), we can still see his brand of madcap whimsy in new games both amateur and professional, both graphical and textual that come out every year. By now his influence is so pronounced that many designers, separated from Planetfall by two or three design generations, don’t even realize whom they’re copying.

I’ve already introduced Meretzky in a couple of articles on this blog. A self-avowed computer hater who was nevertheless chummy with the folks who created Zork at MIT and later founded Infocom, he got the adventuring religion when living as Mike Dornbrook’s roommate. He began to see the possibility of escaping the horrifying prospect of a career in construction management when he began testing Infocom’s games for money with Deadline in November of 1981. He then left construction behind forever in June of 1982, when he became the first salaried member of their new testing department. Meretzky was in Marc Blank’s words “so into it and had so many ideas” that it seemed only natural to let him try his hand at writing a game of his own. In the fall of 1982, at the same time as Stu Galley was starting on The Witness, Meretzky was therefore given carte blanche to write whatever kind of game he’d like. The project he began was a product of his two biggest cultural loves at the time: written science fiction, which he read virtually to the exclusion of anything else, and anarchic comedy on the wavelength of Monty Python, Woody Allen, and Gary Larson.

Planetfall casts you as a lowly Ensign Seventh Class in the Stellar Patrol aboard the SPS Feinstein. The bane of your shipboard existence, the “trotting krip” on whom most of your diary (included in the package) focuses, is Ensign Cadet First Class Blather, who is afflicted with the megalomania of middle managers everywhere. The game begins on just another day aboard the Feinstein, with you wielding your “Patrol-issue self-contained multi-purpose scrub brush” on deck-cleaning duty and trying to stay out of Blather’s way. But then the Feinstein is attacked by forces unknown. You must escape in a life pod, which deposits you next to a research complex of some sort poking above the waves of an otherwise completely water-covered planet. It’s here that your adventure begins in earnest.

The comedies that inspired Meretzky to make Planetfall gain meaning and resonance by saying something about the world in which we live. Monty Python satirizes the hidebound British class system and the prudery of middle-class life; Woody Allen dissects the vagaries of love, sex, and relationships. In The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy Douglas Adams, an author with whom Meretzky would soon be indelibly linked, reveals the manifold absurdities of human social mores, of religion, of how we perceive our place in the universe through his science-fiction comedy of the absurd. Indeed, it’s often been noted that the best science fiction is relevant not so much as a guidepost to the future as for the light it sheds on the way we live and think today. Taking a story out of the here and now allows an author to examine big questions with a clear eye that would be obscured by the vicissitudes of culture and prejudice and emotion if set in our own world.

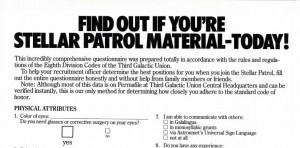

Planetfall, however, doesn’t really try to follow in that tradition. Instead it appropriates some of the broad tropes from Monty Python or Douglas Adams without finding the kernel of social truth at their heart that makes them relevant. The closest it comes is some gentle satire of bureaucracy (the game is packaged in a faux-file folder stamped “Authorized For Issuance”, “Authorized For Authorization”, “Authorized For Rubber Stamping”) and the over-the-top gung-ho-ness of military-recruitment advertisements (“Today’s Stellar Patrol: Boldly Going Where Angels Fear To Tread”, “The Patrol Is Looking For A Few Good Organisms”). On the tree of satire, this is not exactly the highest-hanging of fruits.

Mostly replacing satire in Planetfall is a sort of good-natured goofiness. You can’t fault it for effort. The feelies in particular throw so many gags at you that a few of them are bound to stick. This bit is the one that always makes me laugh:

In the game itself there’s one consistent source of clever humor, which we’ll get to in a moment. But other gags, like the distorted spelling of the aliens who built the complex, start to wear thin after a while. (“Xis stuneeng vuu uf xee Kalamontee Valee kuvurz oovur fortee skwaar miilz uf xat faamus tuurist spot. Xee larj bildeeng at xee bend in xee Gulmaan Rivur iz xee formur pravincul kapitul bildeeng.”) Meretzky was known in Infocom’s offices for his cutting humor, which he deployed against Ronald Reagan and his conservative revolution, against the occasional concerned parent who wrote in to accuse Infocom of preaching Satanism via Zork, against the hordes of besuited businesspeople that Al Vezza began hiring as the Cornerstone project ramped up. It’s a shame the humor of Planetfall and his later games remained so relatively tepid in comparison.

Still, Planetfall has many other strengths to recommend it. It manages to be a beautifully crafted traditional adventure while also expanding the form in notable ways. It’s archetypical in its basic structure: a constricted opening act aboard the Feinstein and the life pod get you into the action, followed by a long middle section (at least 85 percent of the game) allowing for free, non-linear exploration and puzzle solving, which funnels at last into an absolutely cracking set-piece finale. You spend the first part of the long middle collecting information, gradually coming to learn that the aliens who used to live here are not dead but merely in suspended animation, having placed themselves there to avoid a deadly plague that was sweeping the planet and that will kill you as well eventually. It gradually becomes clear that you need to repair the planet’s malfunctioning systems and restart the central computer, which was on the verge of discovering a cure for the disease before it crashed. Repairing the systems is, once again, rather shockingly reminiscent of Starcross, requiring you to decipher simple alien machinery and status displays built around colored lights and the like. (Apparently red is the universal color for bad, green the universal color for good.)

In other respects, however, Planetfall departs radically from Starcross. For all that that game’s environment was infinitely more logical and designed than the world of Zork, it had an unreality of its own, an elegant adventure-game symmetry about it that was nothing like the real world. Each object had a purpose. You spent most of your time collecting and using a set of colored rods which each slotted into a single place. When you got to the finale, every object had been tidily utilized, every room explored and its puzzles solved.

Planetfall, by contrast, gleefully throws elegance and tidiness out the window. You begin the game with two red herrings already in your inventory, and the situation doesn’t improve from there. Planetfall has a dark area you can never explore because there is no light source in the game; an enticing helicopter for which there is no key; a pile of useless spare parts to go alongside the couple you actually need; a bunch of useless (in game terms) bathrooms. This sort of thing was unprecedented in 1983. Adventure games simply weren’t done this way, if for no other reason than designers couldn’t afford to waste the space. Predictably, it drove — and still drives — some players crazy. Now you can’t determine what might be useful for solving a given puzzle from what objects you haven’t used yet, can’t ever get a clear sense of just what still remains to be done and what is just a distraction. Yet it also goes a long way toward making Planetfall‘s world feel believable. Really, and Chekhov’s aphorism of the gun aside, why should every object in a world fall neatly into place by the end? (Perhaps the revelation at the end of Starcross that the whole experience was just an elaborate alien intelligence test, which I criticized in my review, suddenly makes more sense in this light.) Even the most often criticized aspects of the game, its rather sprawling map filled with so many empty or useless rooms and the necessity to eat and sleep, play into the new sense of verisimilitude.

This points to an interesting aspect of Planetfall: for all of the comedic trappings, the scenario and the complex that you explore are quite meticulously worked out. Most things in this world work as they should, sometimes to your detriment; try carrying the magnet at the same time as your magnetic card keys and see what happens. As you get deeper into the story and the tragedy that has happened here starts to become clear, the game deepens, the experience becomes richer. There’s almost a sense of horror that kicks in as you begin coughing and feeling weaker and weaker, and realize you are in a race against time — or, more accurately, against the plague. Here Meretzky departs sharply from Douglas Adams, who never worried about the details of his stories beyond what was needed as a scaffold to support his humor. Planetfall rivals Deadline and The Witness as a lived fictional experience, with the added advantage that it’s not as necessary to constantly restart to see it through.

All of that would be more than enough for one game to add to the established adventure-game template. But of course there’s more. We haven’t even mentioned Floyd.

All of the Infocom games prior to Planetfall had contained non-player characters of one sort or another, but none of those characters had been particularly fleshed-out. Even the mysteries had suffered from the need to include several suspects, which, given the harsh space limitations imposed by the Z-Machine, sharply limited their depth. Planetfall, however, takes place, apart from the brief opening sequence, within a deserted environment. Meretzky realized that he could alleviate the resulting sense of sterility by giving the player a sidekick. Further, this character, being essentially the only one in the game, could have a bit more depth, allow a bit more room for empathy on the part of the player than had been the norm.

Floyd is a “multiple purpose robot” whom you find deactivated in a corner fairly early in your explorations. If you search him before switching him on, you’ll likely wonder why he’s carrying a crayon in one of his compartments. Boy, do you have no idea what you’re in for. Turn him on and he springs to life a few turns later:

Suddenly, the robot comes to life and its head starts swivelling about. It notices you and bounds over. "Hi! I'm B-19-7, but to everyperson I'm called Floyd. Are you a doctor-person or a planner-person? That's a nice lower elevator access card you are having there. Let's play Hider-and-Seeker you with me."

From now on Floyd steals the show. He gets all the best lines. Whenever Floyd is involved, Planetfall becomes as funny as it wants to be. And it becomes something more as well. You fall in love with the little guy.

>play with floyd

You play with Floyd for several centichrons until you drop to the floor, exhausted. Floyd pokes at you gleefully. "C'mon! Let's play some more!"

Floyd notices a mouse scurrying by and tries to hide behind you.

>sleep

You'll probably be asleep before you know it.

You slowly sink into a deep and restful sleep.

...Strangely, you wake to find yourself back home on Gallium. Even more strangely, you are only eight years old again. You are playing with your pet sponge-cat, Swanzo, on the edge of the pond in your backyard. Mom is hanging orange towels on the clothesline. Suddenly the school bully jumps out from behind a bush, grabs you, and pushes your head under the water. You try to scream, but cannot. You feel your life draining away...

***** SEPTEM 7, 11344 *****

You wake up feeling refreshed and ready to face the challenges of this mysterious world.

Floyd bounces impatiently at the foot of the bed. "About time you woke up, you lazy bones! Let's explore around some more!"

Floyd produces a crayon from one of his compartments and scrawls his name on the wall.

>get all

multiple purpose robot: You manage to lift Floyd a few inches off the ground, but he is too heavy and you drop him suddenly. Floyd gives a surprised squeal and moves a respectable distance away.

Floyd rubs his head affectionately against your shoulder.

>s

Machine Shop

This room is probably some sort of machine shop filled with a variety of unusual machines. Doorways lead north, east, and west.

Standing against the rear wall is a large dispensing machine with a spout. The dispenser is lined with brightly-colored buttons. The first four buttons, labelled "KUULINTS 1 - 4", are colored red, blue, green, and yellow. The next three buttons, labelled "KATALISTS 1 - 3", are colored gray, brown, and black. The last two buttons are both white. One of these is square and says "BAAS". The other white button is round and says "ASID".

Floyd follows you.

>save

Ok.

Floyd's eyes light up. "Oh boy! Are we gonna try something dangerous now?"

Floyd pushes one of the dispenser buttons. Fluid pours from the spout and splashes across the floor. Floyd jumps up and down, giggling.

>type 1

The screen clears and some text appears:

"Xe Zoork triloojee, an adventshur klasik, taaks plaas in aa deeliitful but daanjuris undurgrownd seteeng."

"Foor moor deetaald infoormaashun on xis tapik, konsult xe liibrereein foor xe aproopreeit spuulz. Tiip zeeroo tuu goo tuu aa hiiyur levul."

Floyd, peering over your shoulder, says "Oh, I love that game! Solved every problem, except couldn't figure out how to get into white house."

>n

Repair Room

You are in a dimly-lit room, filled with strange machines and wide storage cabinets, all locked. To the south, a narrow stairway leads upward. On the north wall of the room is a very small doorway.

Lying face down at the bottom of the stairs is a motionless robot. It appears to be damaged beyond repair.

>n

It is a robot-sized doorway -- a bit too small for you.

>floyd, n

Floyd squeezes through the opening and is gone for quite a while. You hear thudding noises and squeals of enjoyment. After a while the noise stops, and Floyd emerges, looking downcast. "Floyd found a rubber ball inside. Lots of fun for a while, but must have been old, because it fell apart. Nothing else interesting inside. Just a shiny fromitz board."

>floyd, get board

Floyd shrugs. "If you say so." He vanishes for a few minutes, and returns holding the fromitz board. It seems to be in good shape. He tosses it toward you, and you just manage to catch it before it smashes.

Meretzky may have devoted more text and code to Floyd than had been given to any previous Infocom NPC, but that doesn’t mean it adds up to all that much. Floyd has become a case study in creating more affect with less. In printed form, all of the code and text devoted to Floyd would fill less than ten typewritten pages. There’s very little that you the player can really do to communicate with him or affect his behavior. The gears ought to show through horribly, but somehow they don’t. Floyd’s childlike personality and diction makes it seem a little less weird that he rarely seems to fully understand you when you talk to him. And the relative dearth of text devoted to Floyd can actually work in his favor. We never learn clearly what Floyd actually looks like, although we learn that he has feet (because he can kick us when we fall asleep) and, most strangely, that he can somehow smile. I have a theory that we mentally replace Floyd the robot with whatever strikes us as most appealing — a beloved pet, say, or even a child. Here the medium of text, which lets us all create our own Floyds in our imagination, is key. It makes what eventually happens to him all the more devastating.

There comes another point, like the last one shown above, where you the player are utterly stymied. Once again Floyd comes to the rescue… only this time he pays the ultimate price for his helpfulness.

>look through window

You can see a large laboratory, dimly illuminated. A blue glow comes from a crack in the northern wall of the lab. Shadowy, ominous shapes move about within the room. On the floor, just inside the door, you can see a magnetic-striped card.

Floyd stands on his tiptoes and peers in the window. "Looks dangerous in there," says Floyd. "I don't think you should go inside." He peers in again. "We'll need card there to fix computer. Hmmm... I know! Floyd will get card. Robots are tough. Nothing can hurt robots. You open the door, then Floyd will rush in. Then you close door. When Floyd knocks, open door again. Okay? Go!" Floyd's voice trembles slightly as he waits for you to open the door.

>open door

The door opens and Floyd, pausing only for the briefest moment, plunges into the Bio Lab. Immediately, he is set upon by hideous, mutated monsters! More are heading straight toward the open door! Floyd shrieks and yells to you to close the door.

>close door

The door closes.

From within the lab you hear ferocious growlings, the sounds of a skirmish, and then a high-pitched metallic scream!

>wait

Time passes...

You hear, slightly muffled by the door, three fast knocks, followed by the distinctive sound of tearing metal.

>open door

The door opens.

Floyd stumbles out of the Bio Lab, clutching the mini-booth card. The mutations rush toward the open doorway!

>close door

The door closes.

And not a moment too soon! You hear a pounding from the door as the monsters within vent their frustration at losing their prey.

Floyd staggers to the ground, dropping the mini card. He is badly torn apart, with loose wires and broken circuits everywhere. Oil flows from his lubrication system. He obviously has only moments to live.

You drop to your knees and cradle Floyd's head in your lap. Floyd looks up at his friend with half-open eyes. "Floyd did it ... got card. Floyd a good friend, huh?" Quietly, you sing Floyd's favorite song, the Ballad of the Starcrossed Miner:

O, they ruled the solar system

Near ten thousand years before

In their single starcrossed scout ships

Mining ast'roids, spinning lore.

Then one true courageous miner

Spied a spaceship from the stars

Boarded he that alien liner

Out beyond the orb of Mars.

Yes, that ship was filled with danger

Mighty monsters barred his way

Yet he solved the alien myst'ries

Mining quite a lode that day.

O, they ruled the solar system

Near ten thousand years before

'Til one brave advent'rous spirit

Brought that mighty ship to shore.

As you finish the last verse, Floyd smiles with contentment, and then his eyes close as his head rolls to one side. You sit in silence for a moment, in memory of a brave friend who gave his life so that you might live.

Apart only from the famous white house at the beginning of Zork, this is by far the most remembered scene from any Infocom game. It’s also amongst the most crassly manipulative. Meretzky admits that Floyd’s death was very much a calculated move. Having put so many “eggs in the basket” of Floyd, he asked what the best way would be to “cash in” on that connection. Thus poor Floyd had to die. Planetfall was in final testing when Electronic Arts debuted with the famous “Can a Computer Make You Cry?” advertisement. That made the death scene feel even more appropriate: “There was a little touch of budding rivalry there, and I just wanted to head them off at the pass.”

Perhaps death scenes are like sausages; it’s best not to see how they’re made. Or maybe it doesn’t matter. Floyd’s death still gets me every time, and it seems I’m hardly alone. Significantly, while Floyd’s death is generally described as taking place very near the end of the game, this isn’t always necessarily the case. It’s possible for him to sacrifice himself while there is still quite a bit left to be done before the end-game. Such a scenario might be the most heartbreaking of all, as you’re forced to spend quite a lot of time wandering the complex alone. Without Floyd, it feels sadder and more deserted than ever.

The significance of Floyd and the impact of his death was remarked early and often. Just weeks after Planetfall debuted, Softline magazine shockingly spoiled the game by printing Floyd’s death scene on the front cover(!). Inside was a feature article (“Call Me Ishmael: Micros Get the Literary Itch”) that struggled to come to terms with What Floyd Meant for the evolution of adventure gaming.

The rising level of sophistication in the adventure game — that most sophisticated of entertainments ever to pass through a central processing unit — has fain threatened to take it out of the computer junkies’ realm of private delight and toss it into the center ring of popular culture, along with books, plays, and movies. Can it absorb the culture shock and continue to develop and transcend standards that are already high, or will it be homogenized, simplified, and forced to satisfy the lowest social denominator?

Notably, Marc Blank and Mike Berlyn make a prominent contribution to the article, and here refer for the first time to my knowledge to Infocom’s games as “interactive fiction.”

Floyd was introduced to academia by Janet Murray in 1997’s Hamlet on the Holodeck. Since then he has been a football kicked around in a thousand debates. Some, like Murray, point to him as an example of the emotional potential of ludic narrative, while lamenting that there have been so few similar moments in games since Planetfall. Others, like the ever-outspoken Chris Crawford, point out that Floyd’s death is a pre-scripted, unalterable, non-interactive event, and use it as an example of the fundamental limitations of set-piece storytelling in games. It is, of course, ultimately both.

Less discussed than Floyd’s death — and for good reason — is his return at the end of the game.

A team of robot technicians step into the anteroom. They part their ranks, and a familiar figure comes bounding toward you! "Hi!" shouts Floyd, with uncontrolled enthusiasm. "Floyd feeling better now!" Smiling from ear to ear, he says, "Look what Floyd found!" He hands you a helicopter key, a reactor elevator card, and a paddle-ball set. "Maybe we can use them in the sequel...”

Floyd’s death may have been manipulative, but this is the worst sort of sentimental pandering. It retroactively devalues everything you felt when Floyd made his sacrifice, turning a tragedy into a practical joke — “Ha! Got ya!” I unabashedly hate everything about it. It was added at the behest of marketing, who were in turn responding to distressed playtesters and were concerned about releasing such a “downer” game. As indicated by the extract above, the potential for a sequel starring Floyd was also no doubt in their minds; it had already become clear during testing that players responded to the little fellow as they had to no one in any of Infocom’s previous games. Marketing at Infocom was usually remarkably willing to stay out of the way of artistic decisions. It’s too bad they made an exception here, and too bad Meretzky didn’t stick to his guns and tell them no. As it is, Planetfall goes down as one of a number of Infocom games that fail to stick the landing.

Released in August of 1983, Planetfall was another solid commercial performer for Infocom. It sold some 21,000 copies in the last months of 1983, followed by almost 44,000 the following year, numbers very close to those of The Witness. That’s just a bit surprising in light of Planetfall‘s name recognition today; it stands as one of the best remembered and best loved of the Infocom games, almost entirely due to Floyd, while The Witness goes relatively unremarked except amongst the hardcore. Nevertheless, Trip Hawkins got his answer far sooner than he ever expected to, while today Planetfall‘s legacy as the first computer game to make us cry stands secure.

(I must thank Jason Scott for sharing with me additional materials from his Get Lamp project for this article. There’s also a very good extended interview with Steve Meretzky in Game Design: Theory and Practice.)