Dan Bunten

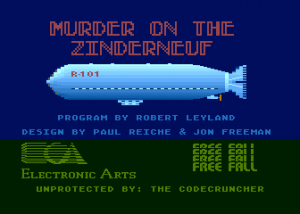

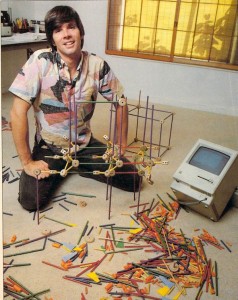

As Electronic Arts got off the ground, Trip Hawkins hired three veterans from his time at Apple — Dave Evans, Pat Marriott, and Joe Ybarra — to become the first people with the job title of “producer” at EA. Their new careers began with a mock draft: Hawkins had them draw lots to determine the order in which they would get to pick the developers they would be working with. Naturally, the three experienced developers all went in the first round, and in the order of their status within established gaming circles. Evans picked first, and chose Bill Budge, the first and arguably still the greatest of the Apple II’s superstar game developers, with name recognition within that community that could be matched by very few others. Marriott chose next, and picked Free Fall Associates, whose Jon Freeman had been responsible for the landmark CRPG hit Temple of Apshai and the Dunjonquest line of sequels and spinoffs that had followed it from Automated Simulations. That left Ybarra with Dan Bunten and his new team Ozark Softscape.

Unlike the others, Bunten had no hits on his resume; his biggest game to date had sold all of 6000 copies. He had previously published through Strategic Simulations, Incorporated, which was the antithesis of Hawkins’s vision of casual consumer software, having been founded by a grognard named Joel Billings to release a series of almost aggressively off-putting computer wargames in the hardcore tabletop tradition. Still, Hawkins had fallen in love with one of Bunten’s SSI games, a business simulation called Cartels and Cutthroats. He had first tried to buy it outright from Billings. When his overtures were rejected, he turned to Bunten himself to ask if he would like to make a game kind of like it for EA. Thus the presence of this B-lister on EA’s rolls, complete with generous royalty and advance. To make things even worse, Ozark was located, as the name would imply, deep inside flyover country: Little Rock, Arkansas. Ybarra certainly didn’t relish the many trips he would have to make there. Little did he realize that the relationship would turn into one of the most rewarding of his career, or that the first game he would develop with Ozark, M.U.L.E., would become the most beloved of all the early titles inside the company, or that it would go on to be remembered as one of the greatest of the all-time classic greats.

Dan Bunten was an idealist from an early age. At university he protested the Vietnam War, and also started a bicycle shop, not to make money but to help save the world. According to his friend Jim Simmons, Bunten’s logic was simple: “If more people rode bikes, the world would be a better place.” When he watched Westerns, Bunten was an “Indian sympathizer”: “It just seems like such a neat, romantic culture, in tune with the earth.” A staunch anti-materialist, he drove a dented and battered old Volkswagen for years after he could afford better. “I felt like I sold out when I bought a 25-inch color TV,” he said. That 1960s idealism, almost quaint as it now can sound, became the defining side of Bunten the game designer. He campaigned relentlessly for videogames that brought people together rather than isolating them. As his most famous quote, delivered at an early Game Developers Conference, went, “No one on their death bed ever said, ‘I wish I had spent more time alone with my computer!'” M.U.L.E. positively oozes that idealistic sentiment. As such, it’s an easy game to fall in love with. Certainly your humble blogger here must confess to being a rabid fanboy.

The seeds of M.U.L.E. were planted back in 1978 when Bunten bought his first Apple II. Educated as an industrial engineer, he at that time was 29, married and with daughter, and seemingly already settled into running a consulting firm doing city planning under a National Science Foundation grant in Little Rock. The eldest of six children, Bunten and his siblings had played lots of board games growing up: “When I was a kid the only times my family spent together that weren’t totally dysfunctional were when we were playing games.” In fact, some of his fondest childhood memories had taken place around a Monopoly board. Dan and his brother Bill had also delved into the world of wargames; when the former was twelve and the latter ten they had designed a complete naval wargame of their own, drawing the map directly onto the basement floor. During a gig working at the National Science Foundation, he had spent some of his time tinkering on their Varian minicomputer with an elaborate football simulation he imagined might eventually become the heart of a Master’s thesis in systems simulation. Now he started working on a game for the Apple II. Right from the beginning his approach to game design was different from that of just about everyone else.

Bunten loved more than anything the social potential of gaming. Setting a precedent that would endure for the rest of his career, he determined to bring some of that magic to the computer. Working in BASIC with only 16 K, he wrote a simple four-player auction game called Wheeler Dealers. He designed a simple hardware gadget to let all four players bid at once. (The details of how this worked, as well as the game software, unfortunately appear to be lost to history.) Then he found a tiny Canadian mom-and-pop publisher called Speakeasy Software to sell the game and the gadget for $54. (Speakeasy’s founder Brian Beninger: “Dan called out of the blue one day and spoke to Toni [Brian’s wife]. She had never experienced an accent from the southern United States and had trouble understanding him…”) Legend has it that Wheeler Dealers was the first computer game ever sold in a box, a move necessitated by the inclusion of the hardware gadget. However, such a claim is difficult to substantiate, as other games, such as Temple of Apshai and Microsoft Adventure, were also beginning to appear in boxes in the same time frame. What is certain is that Bunten and Speakeasy took a bath on the project, managing to sell just 50 to 150 (sources vary) of the 500 they had optimistically produced. In retrospect that’s unsurprising given the game’s price and the limited reach of its tiny publisher, not to mention the necessity of gathering four people to play it, but it did set another, unfortunate precedent: Wheeler Dealers would not be the last Bunten game to commercially disappoint.

Computer Quarterback, in its 1981 incarnation

Still, Bunten had caught the design bug. For his next project, he dusted off the FORTRAN source to his old football simulation. As would befit a Master’s thesis project, that game was the “most thoroughly mathematically modeled” that he would ever do, the deepest he would ever delve into pure simulation. It was, in other words, a great fit for the hardcore grognards at SSI, who released Computer Quarterback as one of their first titles in an all-text version in 1980, followed by a graphical update that took advantage of the Apple II’s hi-res mode in 1981. Typically for SSI, the manual determinedly touts Bunten’s professional credentials in an attempt to justify him as a designer of “adult games.” There is even affixed his seal as a “State of Arkansas Registered Professional Engineer”:

By affixing my seal hereto, I certify that this product was developed in accord with all currently accepted techniques in the fields of operations research, systems simulation, and engineering design, and I further accept full responsibility for the professional work represented here.

It all seems a bit dreary, and an especially odd sentiment from a fellow who would become known for championing easy accessibility to everyday people in his designs. Yet simulation of the real world was in fact a deep, abiding fascination of Bunten, albeit one that would be more obscured by his other design tendencies in his later, mature games. In the meantime, SSI’s audience of the hardcore was big enough to make Computer Quarterback Bunten’s bestselling game prior to his signing with EA, the one that convinced him to quit his day job in city planning and dive into game development full time. Indeed, the aforementioned figure of 6000 sold at the time of EA’s founding would continue to increase afterward; SSI would continue to sell updated versions well into the late 1980s.

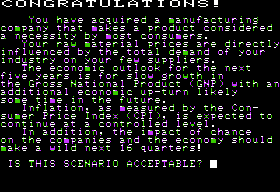

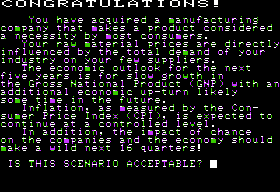

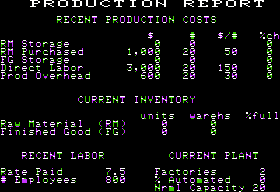

Bunten’s next game was the one that caught Hawkins’s eye, Cartels and Cutthroats. Like Hawkins of the “Strategy and Applied Game Theory” degree, Bunten was fascinated by economic simulations. For help with the modeling of Cartels, an oddly abstracted simulation of the business world — you are told in the beginning only that your company produces either “luxury,” “mixed,” or “necessity goods” — he turned to his little brother Bill, who had recently finished his MBA. Apparently few other gamers of the time shared Hawkins’s and Bunten’s interest in economic simulation; Cartels did not even manage the sales that Computer Quarterback had. Bunten later wryly noted that “evidently folks interested in playing with the stock market or business, do it in real-life instead.” That may to some extent be true, but in my opinion the game’s abstractions do it no favors; it’s hard to get excited about your role as producer of a “luxury good.” Cartels today reads as a step on the road to M.U.L.E.. The later game would continue the economics focus while grounding itself in a much more specific context that the player can really get her hands around.

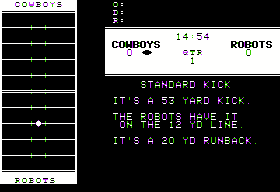

If these early SSI games can seem slightly anomalous to Bunten’s mature work in their unabashed focus on simulation, one thing did stay consistent: they were conceived primarily as multi-player affairs. SSI had to cajole him into putting together a rudimentary opponent AI and single-player mode for Computer Quarterback as a condition of acceptance for publication. Bunten named the computer’s team “The Robots,” which perhaps shows about how seriously he took them. Cartels and Cutthroats offers a number of ways for up to six people to play together, the most verisimilitudinous of which employs a printer to let each player grab her stock reports off the “teletype.” Here computer players, while once more optionally present, still don’t get no respect: now they are called “dummies.”

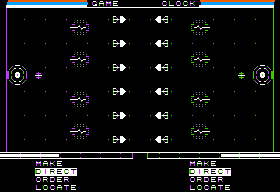

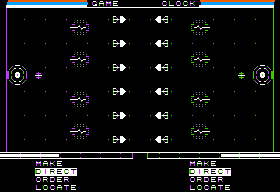

Bunten’s final game for SSI was a marked departure. Released on SSI’s short-lived Rapid Fire line of action-oriented titles, Cytron Masters plays like a prototype of the real-time strategy games that would become popular a decade later. Two players — the two-player mode was again the main focus; the computer opponent’s AI was predictably atrocious — face off on a battlefield of the future in real time, spawning and issuing orders to six types of units. Each player can have up to fifty units onscreen at once, all moving about semi-autonomously. Bunten’s first game to use large amounts of assembly-language code as opposed to BASIC, it was by far his most challenging programming project yet. Cytron had to juggle animations and sound effects while also running the simple AI routines for up to a hundred on-screen units and accepting input from two players, all without becoming so slow as to lose its status as an “action-strategy” game. This presented a huge challenge on the minimalist, aging hardware of the Apple II. As Bunten wrote in a Computer Gaming World article about the experience, “the Apple can’t do two things without a lot of effort (you have to time your clicks of the speaker with your graphic draw routine so that they take turns). It was a tough program to write [emphasis original].”

By this time the Atari 800 was almost three years old, and Bunten had had one “collecting dust” for a pretty good portion of that time. He had remained committed to the Apple II as both the machine with the healthiest software market and the one he knew how to make “sing.” But now he decided to have a go at porting Cytron Masters to the 800. The experience proved to be something of a revelation. At first Bunten expected to just duplicate the game on the Atari. But when he showed the first version to Atari users, they scoffed. “It’s a neat game, but where’s the color? And what are those little noises?” they asked in response to the explosions.

Needless to say, I decided that if the program was to do well as an Atari version, it would have to use a few of the features of that machine. But, during the conversion, I discovered that all the sophisticated hardware features of the Atari are useful! Cytron Masters uses the separate sound processor and four voices to make truly impressive sound effects (at least compared to the Apple); it uses the display list and display-list interrupts to change colors on the fly, and have character graphics, four-color text as well as hi-res graphics on one screen; it uses player/missile graphics for additional colors and fast animation; and most useful of all, it uses vertical-blank interrupts to allow two programs to (apparently) run at once!

Bunten became the latest of a long line of programmers to fall for the elegance of Jay Miner’s Atari 8-bit design, an elegance which the often developer-hostile antics of Atari itself could obscure but never quite negate. He would never develop another game on the Apple II, and the company he was already in the process of forming, Ozark Softscape, would be an Atari shop. (M.U.L.E. never even got a port to the Apple II.)

Cytron Masters was another relative commercial disappointment for Bunten and SSI. “Rather than appealing to both action gamers and strategy gamers,” he later said, “it seemed to fall in the crack between them.” But then, just as Bunten was finishing up the Atari port, Trip Hawkins came calling asking for that sequel to Cartels and Cutthroats and promising that EA could find him the commercial success that had largely eluded his SSI games.

By this point Bunten was already in the process of taking what seemed to him the next logical step in his new career, going from a lone-wolf developer and programmer to the head of a design studio. In a sense, Ozark Softscape was just a formalizing of roles that already existed. Of the three employees that now joined him in the new company, his little brother Bill had already helped a great deal with the design of Cartels and Cutthroats while also serving as a business adviser; Jim Rushing, a friend of Bill’s from graduate school, had offered testing and occasional programming input since the same time; and Alan Watson, formerly a salesman at a local stereo shop, had helped him with the technical intricacies of Cytron Masters and contributed his talents for Atari graphics programming to the port. Now the three came to Ozark largely in the roles they had already carved out. Bill Bunten, the only one to keep his day job (as a director of parks for the city of Little Rock) and the only non-programmer, would handle the administrative vagaries of running a business. Rushing would program, as would Watson in addition to serving as in-house artist. All three would offer considerable design input as well, but they all would ultimately defer to Dan, the reason they were all here. As Rushing later said, “We all knew Dan was a genius.” They were just happy to be along for the ride.

With their EA advance they rented a big house across the street from the University of Arkansas to serve as office, studio, and clubhouse. Each took a bedroom as an office, and they filled the living room and den with couches, beanbag chairs, and of course more computers, making of them ideal spaces for brainstorming and playing. They filled the huge refrigerator in the kitchen with beer, which helped to lure in a crowd of outsiders to play and offer feedback virtually every evening. These were drawn mostly from the biggest local computer club, the Apple Addicts, of which Dan had been the first president back in the days of Wheeler Dealers. He may have defected to the Atari camp since, but no one seemed to mind; at least one or two were inspired by what they saw in the house to buy Ataris of their own. When they grew tired of creating and playing, the house’s regular inhabitants as well as the visitors could exit the back door to walk around an idyllic fourteen-acre lake, to sit under the trees talking or skip rocks across the water. The house and its environs made a wonderful space for creation as well as an ideal laboratory for Dan’s ideas about games as social endeavors to bring people together. It was here that Dan and his colleagues took M.U.L.E. from the germ of a concept to a shipping game in less than nine months.

Said germ was to create a game similar to the rather dryly presented, text-based Cartels and Cutthroats, only more presentable and more accessible, in line with Trip Hawkins’s credo of “simple, hot, and deep” consumer software. They would be writing for the Atari 8-bit line, which in addition to excellent sound and graphics offered them one entirely unique affordance: these machines offered four joystick ports rather than the two (or none) found on other brands. Dan thus saw a way to offer in practical form at last the vision that had caused him to get involved with game design in the first place back in the days of Wheeler Dealers. Four people could gather around the living room, each with her own controller, and really play together, in real time; no need for taking turns in front of the computer or any of the other machinations that had marked his earlier games. This would allow him to create something much breezier than Cartels and Cutthroats — a game to replace the old board-game standbys on family game nights, a game for parties and social occasions. With the opportunity to do those Wheeler Dealers real-time auctions right at last, Dan dusted the old idea off and made it the centerpiece of the new design.

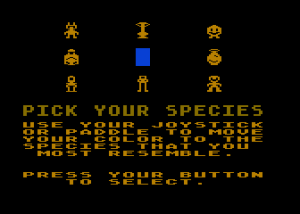

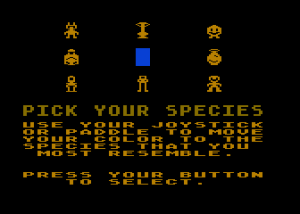

Given their intention to create a family board game for the next generation, Dan and his colleagues started to look at the classic designs for other ideas with which to surround the auctions. The obvious place to look for inspiration for a game with an economic theme was the game that is still pretty much the board game as far as the masses are concerned: Monopoly. Monopoly gets a lot of grief amongst hardcore gamers these days for a multitude of very real flaws, from an over-reliance on luck in the early stages to the way it often goes on forever after it becomes totally obvious who is going to win to the way it can leave bankrupted players sitting around with nothing to do for an hour or more while everyone else finishes. Yet there’s something compelling about it as well, something more than sheer cultural inertia behind its evergreen appeal. The team now tried to tease out what those qualities were. Bill Bunten said, half facetiously, that his favorite thing about Monopoly was the iconic metal tokens representing each player — the battleship, the car, the top hat, the shoe, etc. Everyone laughed, but the input became an important part of the new game’s charm: every player in it gets to pick the avatar she “most resembles.”

Looking more deeply for the source of Monopoly‘s appeal, the team realized that it was socially- rather than rules-driven. Unlike most board games, which reward the analytical thinker able to maximize the interactions of a rules set, Monopoly — at least if you’re playing it right — rewards the softer arts of negotiation and diplomacy. The personalities of the players and the relationships among them have as much effect on the way play proceeds as do the rolls of the dice. In the Bunten family, Mom would always let you out of paying rent if you couldn’t afford it; Bill would force you to mortgage a property if you came up a dollar short on your rent. Alliances and partnerships would form and shift as a result. The team decided that they wanted that human element in their game. It had never been seen in a computer game before, for the very simple reason that it was beyond the scope of possibility for an AI opponent living in 48 K of memory. But in their game, conceived primarily as a multi-player experience, it should be possible.

And yet more elements were drawn from Monopoly. Play would center around a “board” of properties which would be gradually acquired by the players, through a land grant that began each turn or through auctions or trades. They also built in equivalents to Monopoly‘s Chance and Community Chest cards to keep play from getting too comfortable and predictable. In keeping with Dan’s roots in simulation, however, the game would attempt to model real economic principles, making its theme more than just the window-dressing it largely was in Monopoly. Producing the same good in two adjacent plots would let the player take advantage of economies of scale to produce more; having three plots in total producing the same good would also result in more production, thanks to the learning curve theory of production. In general, the computer allowed for a deeper, more fine-grained game model than was possible in dice and cardboard. For instance, normalized probability curves could be used in place of a six-sided die, and the huge sums of money the players would eventually accumulate could be tracked down to the dollar. It all would result in something more than just a computerized board game. It would be a real, functioning economy, a modest little virtual world where the rules of supply and demand played out transparently, effortlessly from the players’ perspective, just as they do in the real world.

But what should be the fictional premise behind the world? For obvious commercial reasons — Star Wars and Star Trek were huge in the early 1980s — they decided early on to give the game a science-fiction theme. Dan and Bill had both read Time Enough for Love by Robert Heinlein. Dating from the early stages of Heinlein’s dirty-old-man phase, there’s not much to recommend the book if you aren’t a fan of lots and lots of incestuous sex written in that uniquely clunky way of aging science-fiction writers who look around to realize that something called the Sexual Revolution has happened while they were hanging out at science-fiction conventions. Still, the brothers were inspired by one section of the book, “The Tale of the Adopted Daughter,” about a colony that settles on a distant planet. Provided with only the most meager materials for subsistence, they must struggle to survive and build a functioning economy and society by the time the colony ship returns years later to deliver more colonists and, more importantly, haul away the goods they produced to make a profit for everyone back in the more civilized parts of the galaxy. Sounds like a beautiful setup for a game, doesn’t it? To add a realistic wrinkle, the team decided that each of the four players would not only be working for herself, but must balance self-interest with the need to make the colony as a whole successful by the time the ship returned. Thus entered the balancing act people working in real economies must come to terms with, between self-interest and the needs of the society around them. A player who gets too cutthroat in her attempts to wring every bit of profit out of the others can bring the whole economy crashing down around her ears. (Perhaps some banking executives of recent years should have played more M.U.L.E. as youngsters.)

Among the most valuable tools that Heinlein’s colonists bring with them is a herd of genetically modified mules that are not only possessed of unusual strength and endurance but also so intelligent that they can engage in simple speech. The fact that the mules are nevertheless bought and sold like livestock makes this just one more squicky aspect of a very squicky book; it feels uncomfortably like slavery. Obviously that wouldn’t quite do for the game. Then one day Alan Watson’s son came in with a toy model of an AT-AT Walker from The Empire Strikes Back. It only took the removal of the guns and the addition of a listlessly shambling gait to go from Imperial killing machine to cute mascot. A hasty backronym was created: mules were now M.U.L.E.s, Multi-Use Labor Elements programmable to perform any of several different roles. They provided the pivot around which the whole experience would revolve.

He [a M.U.L.E.] was born — if you can call it that — in an underground lab in the Pacific Northwest. A major defense contractor had gone out of its way to get the job and they were stoked.

Stoked, this is, until the detailing robots went on strike. Costs ran over. Senators screamed. And when the dust had cleared, the job was finished by a restaurant supply firm, a maker of preschool furniture, and the manufacturers of a popular electric toaster.

It shows.

The game itself was quickly renamed from the underwhelming Planet Pioneers to M.U.L.E., albeit not without some conflict with EA, who pushed for the name Moguls from Mars. Thankfully, M.U.L.E. won the day in the end.

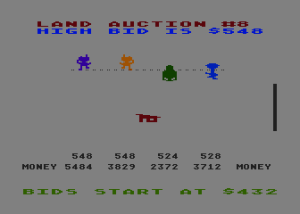

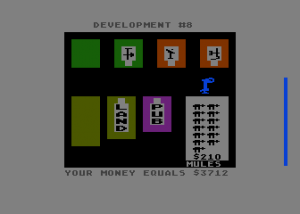

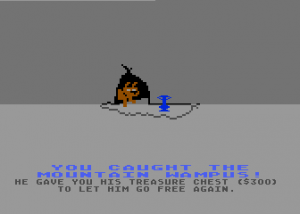

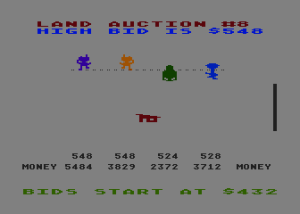

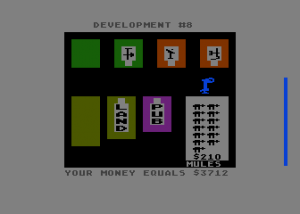

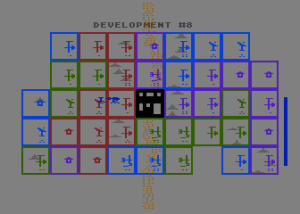

Combined with the Monopoly-inspired player avatars, the M.U.L.E.s anchored the game in a concrete reality, offering it an escape from the abstraction that had limited the appeal of Cartels and Cutthroats. Now the player could be embodied in the economic simulation. She didn’t just assign one of her plots to produce, say, smithore (the colony’s main cash crop, which requires food and energy to produce) from some textual display. No, she had to walk into the village at the center of the colony, buy a M.U.L.E., outfit it for the right sort of work, then lead it back to her plot. And now auctions could be implemented as a unique combination of footrace and game of chicken involving all of the players’ avatars. All of this is done entirely with the joystick, forming a GUI interface of sorts perfectly in line with Trip Hawkins’s vision of a new generation of friendly consumer software. The new “visual, tactile relationship” (producer Joe Ybarra’s words) between player and game also allowed some modest action elements to keep players on their toes: they had only a limited amount of time to try to accomplish everything they needed to — buying M.U.L.E.s, reequipping and rearranging them to suit current production needs, etc. — during their turn. Running out of time or misplacing a M.U.L.E. (thus causing it to run off) could be disastrous; conversely, working quickly and efficiently, and thus finishing early, gave time to earn some extra money by gambling in the pub, or, in an homage to Gregory Yob’s classic, go hunting for the “mountain wampus.” The latter was just one of many elements of whimsy the team found room to include, one more drop in M.U.L.E.‘s bucket of charm.

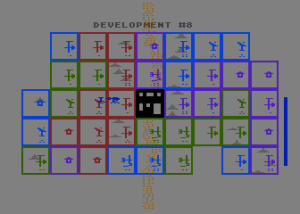

A land auction in progress.

About to buy a M.U.L.E. in the village.

Leading a M.U.L.E. from the village at the center of the game board for placement in an empty plot (denoted by the house symbol) at far left.

Hunt the “Wampus”

With the core ideas and mechanics now in place, Dan Bunten and his colleagues had the makings of one hell of a game on their hands. But as any good game designer, whether she works in cardboard or silicon, will tell you, even the most genius of designs must be relentlessly tested, endlessly tweaked. Ozark Softscape and EA devoted literally months to this task, gradually refining the design. Land had originally all been sold through auctions, but this soon became obviously problematic: once a player got fairly well ahead, she would be able to buy up every plot that became available, putting her economy in a different league from everyone else’s and making the outcome a foregone conclusion as early as halfway through the game. They solved this by automatically granting one plot of land to each player on every turn, only supplementing those grants with the occasional plot that came up for auction. They also added several other little tweaks designed to keep anyone from completely running away with the game. For instance, a bad random event can never happen to the player in last place, while a good can never happen to the player in first. In case of ties in auctions or land grants — two or more players arriving somewhere or pressing their buttons at the same time — priority always goes to the player furthest behind.

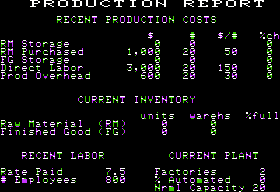

And then of course the economy itself — the exact relationship between supply and demand, the prices of the different commodities and the ways they fluctuated — required a multitude of adjustments to find the perfect balance.

The game was designed to always have four players, with the seats of any absent humans being filled by computer opponents. This required the development of AI. While obviously not the main point of M.U.L.E., the team to their credit did a pretty good job with that; the computer often makes smarter moves than you might expect. Single-player M.U.L.E. is a pale shadow of multi-player M.U.L.E., but it’s hardly a disaster. (As Dan later wrote, “Single-player M.U.L.E. is considerably better than single-player Monopoly!”) It’s even possible to let four computer opponents play while you sit back and watch, something that stores looking to feature the game in their sales windows must have greatly appreciated.

Ozark relied for all of the exhaustive and exhausting testing required to get everything right not only on the endless stream of eager players who visited their house each night but also on others back at EA. Both Hawkins and Ybarra made considerable contributions to the design. Hawkins pushed always to make M.U.L.E. as realistic an economic simulation as its premise and the need for accessibility — not to mention the limited capabilities of the Atari 800 — would allow. Later he wrote the manual himself; like the game, it’s a model of concise, friendly accessibility, designed to get the player playing with an absolute minimum of tedious reading. As for Ybarra… well, here’s his level of dedication to a project of which he had started out so skeptical:

Right about the mid-point of the product, when we were starting to get [the] first playable [builds], that was when I started my several-hundred hour journey of testing this game. I can remember many nights I would come home from work and fire up the Atari 800 and sit down with my, at the time, two-year-old daughter on my lap holding the joystick that didn’t work, while I was holding the joystick that did work, testing this game. And I’d probably get eight or ten games in at night, and I would do that for two or three or four months actually, trying to work out all the kinks in the product.

By the way, at that time in the history of EA, we had no testers. In fact we had no assistance—we didn’t have anything! So producers had to do everything. I tested my own products; I built my own masters; I did all the disk-duplication work; I did all the copy-protection; I did the whole nine yards! If it was associated with getting the product manufactured, the producers did all the work. I remember a lot of nights there staying up until one or two o’clock in the morning playing M.U.L.E. and thinking, “Wow, this game is good!” It was a lot of fun. And then thinking to myself, “Gee, I wish the AI would do this.” So I took notes and took them along to Dan, and said “If you do these kinds of things at this point in the game, this is what happens.” He would take parts of those notes, and a couple of days later I’d get a new build and be back in that main chair back with my daughter on my lap, once again testing this thing and checking to see if it worked. More often than not, it did. That was a really special time.

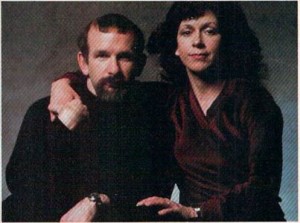

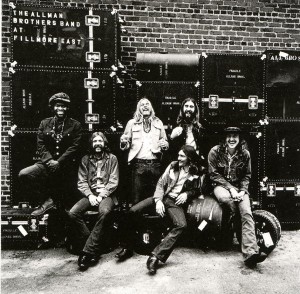

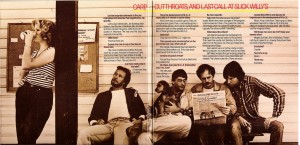

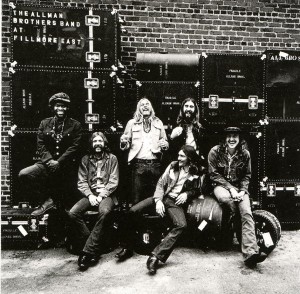

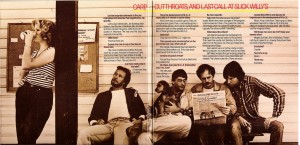

As the game neared completion just in time for EA’s own launch as a publisher, the EA PR folks went to work. Hewing always to the “software artists” dictum, they cast Ozark Softscape as a group of hip back-country savants, sort of the gaming equivalent of the Allman Brothers Band. Their portrait on the inner sleeve of M.U.L.E. even bears a certain passing resemblance to the Allmans’ iconic At Fillmore East cover.

Seated from left: Bill Bunten, Jim Rushing, Alan Watson, Dan Bunten

Like all of this software-artists stuff, it was a bit contrived. The girl Bill Bunten is apparently ogling like a real rock star on the prowl is actually his sister, hastily recruited to add an element of additional interest to the picture.

Heartbreakingly, the image-making and advertising didn’t get the job done. Despite all the love lavished on M.U.L.E. by Ozark Softscape and EA and despite deservedly stellar reviews, it was a commercial disappointment. M.U.L.E. sold only about 30,000 copies over its lifetime. By way of comparison, consider that Pinball Construction Set, another launch title, shifted over 300,000 units. Some of the disappointment may be down to M.U.L.E.‘s debuting on a relative minority platform, the Atari 8-bit line. Although it was later ported to the juggernaut Commodore 64, it was kludgier away from the Atari and its four joystick ports. Even the latest iteration of the Atari 8-bit line, the 1200XL, couldn’t play M.U.L.E. properly, thanks to Atari’s decision to reduce the four joystick ports to two in the name of cost reduction. Out of all the disappointments engendered by that very disappointing machine, this was perhaps the most painful. Thus M.U.L.E., the Atari 8-bit’s finest gaming hour, plays properly only on a subset of the line.

But likely even more significant was a fact that was slowly becoming clear, to Dan Bunten’s immense frustration: multi-player games just didn’t sell that well. It really did seem that most of the people buying computer games preferred to spend their time alone with them. Reluctantly recognizing this, even he would soon be forced by commercial concerns to switch to the single-player model, at least for a couple of games.

Yet we can take comfort in the fact that M.U.L.E.‘s reputation has grown to far exceed its commercial performance. Indeed, it’s better remembered and better loved today than all but a handful of the contemporaries that trounced it so thoroughly in the marketplace back in the day. And deservedly so, because playing M.U.L.E. with a group of friends is a sublime experience that stands up as well today as it did thirty years ago. The world is a better place because it has M.U.L.E. in it, and every time I think about it I feel just a little bit happier than I was before. Just a few notes of its theme music (written by a Little Rock buddy of the Buntens, Roy Glover) puts a smile on my face. If the reasons for that aren’t clear from all the words that have preceded these, that may be down to my failings as a writer. But it may just also be down to the way that it transcends labels and descriptions. If ever a game was more than the sum of its parts, it’s this one. I could tell you at this point how such gaming luminaries as Sid Meier, Will Wright, and Warren Spector speak about M.U.L.E. with stars in their eyes, but instead I’ll just ask you to please go play it.

There are modern re-creations on offer, but purists like me still prefer the original. In that spirit, here’s the manual and Atari disk image, which you can load into an emulator if, like most of us, you don’t have an old Atari 800 lying around. Pick up some old-time digital joysticks as well and then hook a laptop up to your television to really do the experience right. That’s the way that M.U.L.E. should be played — gathered around the living room with good friends and the snacks and beverages of your choice. At some point during the evening remember to look around and remind yourself in best beer-commercial fashion that gaming doesn’t get any better than this. And maybe drink a toast to the late, great Dan Bunten while you’re at it.

Update, August 1, 2023: The Dan Bunten of this article began to live as the woman Dani Bunten Berry in 1992; she died in 1998. I knew less about transgenderism at the time that I wrote this article than I do now, and would certainly have written it differently today. Which doesn’t, of course, mean that my handling of it would satisfy everybody. These are complicated issues, balancing fidelity to history against the rights of individuals to determine their own gender identities, potentially even retroactively. As such, reasonable people of good faith can and do disagree about them. For a fairly long-winded a description of my current opinions and editorial policy on these matters, thought through in a way they sadly weren’t at the time I wrote this article, see a comment I wrote elsewhere on this site in 2018.

(Sources: Dan wrote a column for Computer Gaming World from the July/August 1982 issue through the September/October 1985 issue. Those are a gold mine for anyone interested in understanding his design process. Particularly wonderful is his detailed history of M.U.L.E.‘s development in the April/May 1984 issue. Other interesting articles and interviews were in the June 1984 Compute!’s Gazette, the November 1984 Electronic Games, and the January 1985 Antic. Online, you’ll find a ton of historical information on World of M.U.L.E. Salon also published a good article about him ten years ago. Finally, see the site of the (apparently stalled) remake Alpha Colony for some nice — albeit somewhat buried — historical tidbits. And sorry this article runs so long. M.U.L.E. is… special. I really wanted to do it justice.)