Dan Gorlin was 27 years old in early 1981, and already possessed of the sort of multifarious resume that’s typical of so many we’ve met on this blog. He was just coming off a three-year stint with Rand Corporation, doing artificial-intelligence research, but before that he’d studied piano at the California Institute of the Arts, and also studied and taught African dance, music, and culture. Now the Rand gig was over, and he suddenly found himself with time on his hands and no great urgency to find another job right away; his wife was earning very well as an oil-industry executive. While staying home to show prospective buyers the Los Angeles house he and his wife had put up for sale, Gorlin started tinkering for the first time with a microcomputer, an Apple II Plus that belonged to his grandfather. Said grandfather, a hopeless gadget freak, loved the idea of a PC, but in actuality hardly knew how to turn the Apple II on; he called floppy disks “sloppy disks” out of genuine confusion. So, Gorlin had no difficulty keeping the machine at his house for weeks or months at a stretch.

He wasn’t using the Apple II to play games. Indeed, as he has repeatedly stated in interviews, Gorlin has never been much of a gamer. He was rather intrigued by what he might do with the Apple II as a programmer, what he might create on it. He started learning the vagaries of the Apple II’s hi-res graphics, the bitmapped display mode that many computers in 1981 still lacked. Amongst his other passions, Gorlin was fascinated by helicopters, so he started developing a program that would let a player fly a little helicopter around the screen using the joystick. At first he attempted to implement a pilot’s-eye view, showing the view from the cockpit in three dimensions, Flight Simulator-style, but eventually gave up on this as too taxing, settling for a third-person view of his little helicopter. Still, he tried, to the extent possible on a 48 K 8-bit computer, to make his program an accurate simulation of the rather odd and counter-intuitive physics of helicopter flight. Eventually he had a very acceptable little helicopter simulator running, if also one that was very tricky to fly.

He may have had the physics of flight in place, but Gorlin, who couldn’t help but notice by this point that others were making serious money selling Apple II games, needed a hook, a reason for flying the helicopter that could turn his simulator project into a real game with challenges and a goal. He tried adding some enemy tanks and planes to shoot at and be shot at in standard arcade fashion, but it somehow still didn’t feel right. Then one fateful afternoon a local kid whom Gorlin had hired to do some repairs on his car was playing around with the program. “You should have some men to pick up,” the kid said — like in one of his favorite arcade games, the mega-popular Defender. Gorlin, non-gamer that he was, knew nothing about Defender, so he walked over to the local laundromat to have a look.

Defender is in many ways a typical creation of its time, with the player tasked with shooting down wave after wave of enemy ships to increase her score and earn extra lives. It does, however, have one unique element, from whence derives its name. Little “astronauts” wander the planet’s surface at the bottom of the screen. In an unexpected injection of Close Encounters into Star Wars, certain enemy ships attempt to abduct these fellows. If they succeed in carrying one off, the player has one last chance to effect a rescue: she can shoot down the offending ship, scoop up the falling astronaut, and set him down safely back on the planet’s surface. If enough astronauts get abducted (or killed falling from their destroyed abductors), the planet explodes and an onslaught of particularly deadly enemies begins, until the player either dies (most likely) or manages to revert everything back to normal by killing them all.

Defender‘s astronauts function more as a mechanical gimmick to differentiate the game from its peers than an earnest attempt at ludic worldbuilding, but they were enough to get Gorlin thinking about a new and unique goal for his own game. What if, instead of making the goal to shoot down enemies for points, he instead made it to rescue unarmed hostages for, well, the sake of doing good? It was a scenario very much in step with the times. In April of 1980, President Jimmy Carter had authorized sending six helicopters to attempt to rescue the 52 Americans being held hostage in Tehran following the Iranian Revolution of the previous year. The mission turned into an infamous fiasco which cost eight Americans on the mission their lives without ever even making contact with a single hostage — or Iranian for that matter — and arguably cost Carter any hope he might have still held for reelection later that year. Oddly, Gorlin says that he never made the obvious connection between his developing idea and the recent event in Iran until he started showing his game in public and heard people talking about it. Still, it’s hard not to feel that the influence must have been at least subconsciously present from long before that point. It’s certainly safe to say that most of the people who eventually made Choplifter one of the biggest Apple II hits of 1982 saw it as a direct response to an humiliation that still smarted with patriotic souls two years later, a chance to re-stage the mission and this time get it right.

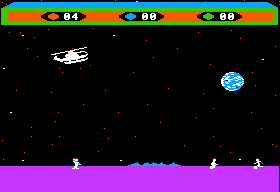

By late 1981 all of the basic concepts of Choplifter had been implemented. While the enemy tanks and planes remained, they were now mere hindrances to be destroyed or — often preferably, because it wasted less time — avoided. The real goal was to rescue as many of the 64 hostages wandering the surface below as possible. You did this by landing the chopper next to them — but not directly on them, lest you crush them — and letting them climb aboard before an enemy tank could kill them. Once you had a pretty good load of hostages (your helicopter could hold up to 16), you needed to drop them off safely back at your base. The only score was the number of hostages you could manage to rescue before you lost the last of your three lives, or ran out of living hostages to carry away. If a new player could end up with more living than dead she was doing pretty well, and rescuing all 64 remains to this day one of the truly herculean feats of gaming lore.

Convinced that he “could make some money” with the game, Gorlin sent his prototype to Brøderbund, who had followed Apple Galaxian/Alien Rain with a wave of other, thankfully mostly more original titles that had garnered them a reputation as a premier publisher of Apple II action games. They loved Choplifter from the moment they booted it, and immediately flew Gorlin out to their new San Rafael headquarters to help him to polish it and to talk contract. Like so many others, Gorlin expresses nothing but warmth for Brøderbund and the Carlston siblings: “So the way they did it was, they’d see something that was like, it’d have promise, and they’d sort of engulf you with family love. It was a very nurturing environment.”

Brøderbund’s enthusiasm proved to be justified. When they started showing Choplifter at AppleFest and other trade shows that spring, people lined up “around the block” to play it. And when released in May of 1982, the game sold 9000 copies in its first month on the market, excellent numbers in those times. But that was only the beginning. Over the months and years that followed Brøderbund funded ports to virtually every viable platform that came along. And, in a move that must have made people wonder whether the earth was about to start orbiting the moon, Sega even bought a license to make a standup-arcade incarnation in 1986, a reversal of the normal practice of bringing arcade games to home platforms.

Gorlin worked on and off in the games industry over the years that followed, but often with the lack of enthusiasm we might expect from such a defiant non-gamer. He never had another high-profile success to match Choplifter, and his most abiding passion remains African dance. Still, with Choplifter‘s huge sales and Brøderbund’s very generous royalty rates even for ports and translations with which he had no direct involvement, he did very well for many years off his one big moment of glory. Even today when his name is mentioned it tickles at the back of many a long-time gamer’s mind, where it’s been rattling around for years after appearing on all those Choplifter title screens and boxes.

But what was it that made Choplifter so compelling to so many people? And, you might be wondering as a corollary, why am I devoting time to it on a blog that’s usually all about games with strong narrative elements? One immediate answer, at least to the former question, is that Gorlin was fortunate enough to create something perfectly in step with the zeitgeist of the early 1980s, when helicopter-based rescue missions and hostages were so much on people’s minds. Indeed, Gorlin himself has always mentioned this good fortune as a key to the game’s success. But in addition, and more importantly for our purposes, Choplifter is not just another action game. It’s doing something different from most of its peers, something that makes it worth talking about here in the same sense that Castle Wolfenstein was. It marks a step toward story, or at least real, lived experience, in a game that is not an adventure or CRPG.

Mind you, you won’t find a compelling story in the conventional sense attached to Choplifter. The manual justifies the action by explaining that the Bungeling Empire, a group of generically evil baddies invented by the Carlston brothers who appear in many early Brøderbund games, have kidnapped the 64 delegates to the United Nations Conference on Peace and Child Rearing they were hosting. (What could be more evil than to use violence against that conference?) Luckily, the United States has for some reason been allowed to build a post office(!) within Bungeling territory, into which they’ve smuggled “an entire helicopter disguised as a mail sorting machine.” You can use the reassembled helicopter to rescue the hostages and return them to the post office. It’s a typically silly action-game premise, obviously not meant to be taken too seriously.

No, it’s other aspects of Choplifter that make it interesting for my purposes, that make it feel like it wants to be an experiential game in a way that its peers don’t. One immediately noticeable difference is the aforementioned rejection of a scoring mechanic or a leaderboard. Your success or failure are measured not by some abstract, extra-diegetic numbers, but rather by two figures that have heaps of meaning within the world of the game: how many hostages you rescued and how many you allowed to be killed. Further, there is a definite end-point to Choplifter that involves more than the three avatar lives you have at your disposal. In addition to (naturally) ending when these are exhausted, the game ends when the supply of hostages is exhausted — when all have been killed or rescued. Complete failures, disappointments, tragedies, mixed outcomes, relative successes — and, for the holy grail, the complete victory of rescuing all 64 innocents — are possible. Contrast that with the kamikaze run that was the standard arcade game of the time, where you simply played until you ran out of lives.

For the first run you make to rescue hostages, you don’t have to contend with any enemy aircraft, only some ground-bound tanks. Next time, the enemy jets start to show up. In one sense this is a standard arcade mechanic, of offering up tougher and tougher challenges as the player stays alive longer. In another, though, it’s a realistic simulation of the situation. The first time you fly out with your smuggled-in helicopter, you catch the Bungelings by surprise, and thus have a fairly easy time of it. Afterward, however, they know what you’re about, and are marshaling their forces to stop you. As you fly back again and again into ever-increasing danger, there’s a sense of a plot building to its climax.

The in-game presentation consistently enforces this sense of inhabiting a real storyworld. The graphics obviously cannot look too spectacular, given the limitations of their platform, but the behavior of the hostages in particular has a verisimilitude that can actually be kind of touching. When you first fly over a group, they stand and wave, desperately trying to attract your attention. When you fly closer, and it becomes clear that you’re trying to pick them up, they all rush frantically toward you. Should enemies get in the way, their behavior is almost as unpredictable as would be that of real civilians who suddenly find themselves on a battlefield. Some run away, figuring that remaining captive beats dying, while others dash madly toward the helicopter, and are often killed for their rashness. It takes those that do reach the helicopter a nail-biting moment to scramble inside. Hover just overhead and they jump frantically underneath you, trying to get aboard. Later, when you fly them back to the post office, they pile out of the helicopter and rush for the sanctuary of the building — but a few, just a few, pause for a moment to turn and wave back in thanks.

Other arcade games, like Donkey Kong, had brought a similar sense of characterization to their actors, but the emergent qualities and realistic strictures of Choplifter nevertheless make it feel real in a way that those games don’t. There’s the fact that you can, for example, only pack 16 hostages at a time into your helicopter. And of course there’s the already-mentioned gruesome possibility of crushing hostages if you land on top of them. Elements like this can make Choplifter feel off-putting at first if you approach it as just another classic arcade game. We don’t expect real-world logic to mix with game logic in quite that way, even though it would make perfect sense not to, you know, land on people’s heads if we were actually in that situation.

Another critical element is the behavior of the helicopter itself. Gorlin had originally envisioned Choplifter as a realistic simulation of actual helicopter flight, but a helicopter is about the most notoriously difficult type of aircraft there is to fly. Brøderbund convinced him that hewing too stubbornly to real helicopter physics would limit the appeal of the game far too much. Gorlin:

They taught me about playability. They helped me with control of the joystick.

The first Choplifter I showed Brøderbund was too realistic, too much of a helicopter simulation. De-emphasizing the weight of the calculations that simulated the vertical force control of the rotors made the chopper more flyable to the average player. I hated to see the realism go, but it did improve the game. In a lot of ways, Brøderbund helped me fine-tune and polish the presentation.

It’s important to note, however, that Brøderbund did not have Gorlin remove all of the realism. They just had him scale it back to a manageable level. What they achieved was — and this is important enough that I’m almost tempted to call it visionary — a sort of videogame hyper-realism. The helicopter’s motions are sloppy and unstable enough that you still feel like you’re really flying. It’s a very different experience from the clipped, precise controls of other arcade games, like Choplifter‘s partial inspiration Defender. Choplifter achieves the neat trick of making you feel like a real pilot without demanding that you acquire the skills of a real pilot first. That alone makes it an important step on the road to truly experiential action games. Choplifter consistently invites us to enter a storyworld, to play with our imaginations as well as our reflexes.

When a game of Choplifter is, one way or another, over, two simple, classic words appear on the screen: “The End,” reinforcing yet once more this sense of the game as a lived story. In a fascinating article in the July 1982 Softline, Jim Salmons heavily emphasized this and the other cinematic qualities of the game, marking it as an early case study in the long, fraught relationship between videogames and movies. Some of his conclusions do rather stretch the point, but the fact that Choplifter was inspiring people to see it in such a way is significant in itself. Salmons describes the game in a way that makes it sound at home with the ludic rhetoric of modern “serious games,” or for that matter some of the contemporary Edu-Ware simulations. On the player’s power to choose to what extent she goes after the enemy tanks and planes in lieu of simply trying to rescue the hostages:

Your temperament and values determine whether aggressive behavior is warranted. Sometimes, you can’t avoid it. On other occasions, it’s righteous reflex, as in retaliation for an enemy tank having just obliterated a huddled mass of frightened hostages.

No matter what heroics were involved, when all hostages are accounted for or all choppers lost, a transformation occurs. The eyes of the hero turn into the eyes of a general reading the dead and rescued statistics. What is the measure of success? Were three helicopters lost worth the return of six hostages? Though sixty returned, did four have to die?

Is Salmons going too far in turning Choplifter into a soul-searching exercise about the wages of war? Perhaps, at least a bit. But isn’t it interesting that the game managed to encourage such flights of fancy?

With its focus on rescue rather than destruction and its do-gooder plot, Choplifter today feels like a perfect symbol for Brøderbund themselves, about the nicest bunch who ever got filthy rich in business. We’ll hear more from them later, but next, as always, it’s on to something else. If you’d like to try Choplifter for yourself in the meantime, here’s the Apple II disk image for you.