I’ve already introduced some hackers on this blog who defied pop-culture stereotypes of blinkered nerddom with a remarkable range of interests and activities outside of computers. Marc Blank, for example, managed to finish medical school while moonlighting with MIT’s Dynamic Modeling Group, where he learned enough to become the most important technical architect behind Infocom’s technology. Andrew Greenberg of Wizardry fame went on to become a lawyer, and now “hacks the law with glee.” In its essence the attraction of hacking is the joy of coming to understand a complex, dynamic, semi-autonomous system, and then bending it to your will. Plenty else in the modern world beyond computers offers some of the same experience, medicine and law perhaps not least among them. Not to mention, to choose an obvious parallel for this blog, games.

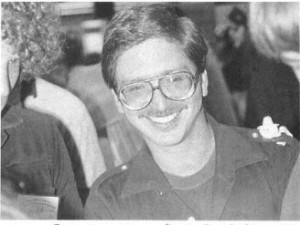

The fellow I want to introduce you to today, Doug Carlston, had a background at least as eclectic as anyone I’ve mentioned earlier. Born in 1947 as the son of a Harvard-educated theologian, Doug by the time he was 30 already had a dizzying resume to his name: a Bachelor’s in social psychology from Harvard, studies in international economics at Johns Hopkins, and a law degree from Harvard Law School. In addition to his studies, he had also run a business designing and building houses; spent a year teaching in Botswana; written an introductory textbook on Swahili; written other language guides for American Express. But by 1977 Doug, two years out of law school, was bored, stuck with an uninteresting job with a huge law firm on the 82nd floor of Chicago’s Sears Tower. As a junior lawyer, he got “the kind of work nobody else wants to do,” like conducting client surveys and doing wills and trusts. Feeling “fat and slow” in addition to bored, he packed up and moved to a small town in Maine with a view to getting back to nature. There he set up an independent law practice serving the locals. That proved to chiefly mean defending clients who ran afoul of the stiff local hunting ordinances. Trouble was, virtually all of his clients were clearly guilty, and many never bothered to pay him for his services, making the practice both uninteresting and not terribly lucrative. To help with the latter problem, Doug began to dabble once again in housebuilding in addition to the law. Helping with the former was the TRS-80 he’d bought, ostensibly to help with bookkeeping at the office. Now, however, he just couldn’t stop playing with it.

The TRS-80 was far from Doug’s first exposure to computing. In fact, computing was yet another of those myriad of interests and activities that had marked his life to that point. He had been introduced to computers as early as 1964, when he attended a sort of summer camp for gifted teenagers who might be interested in becoming engineers. There he first dabbled in FORTRAN programming, finding it fascinating. When he went off to Harvard, he found a job there as a “programming assistant,” basically a tutor to help other students bend the machines to their will. When the time came to lock up the computer lab for the day, Doug and his buddies would stuff chewing gum into the locks so that they could sneak back in in the middle of the night and hack. Still, by the time he bought his TRS-80 in 1978 those days were many years in the past.

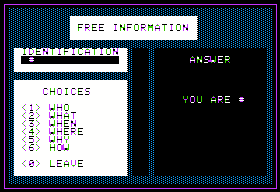

The TRS-80 served to reignite the old passion. Doug did use it to code programs useful to his practice, but he also embarked on an ambitious game, which he called Galactic Empire. It’s a work of considerable historical importance in its own right, quite apart from its place in Doug’s career. It was, you see, the first recognizable example of a “4X” (“explore, expand, exploit, exterminate”) grand strategy game to appear on a PC, the ancestor of such seminal later titles as Civilization and Master of Orion. The player begins Galactic Empire with a single medium-sized planet and a fleet of 200 ships. From this starting point she is expected to conquer the 19 other worlds of the game’s galaxy. Along the way she must manage each conquered planet’s economy, juggling taxes and population, in order to build more ships for her fleet. As you would expect of a game written in BASIC on a 16 K TRS-80, Galactic Empire is absurdly stripped down and primitive in comparison to its successors. Yet the core attributes — and the vision — are there.

What happened next will be familiar to anyone who read my earlier articles about other pioneers of the early software industry. Doug came up with some packaging and began selling his game directly to local computer stores, as well as through outlets for semi-professional software like SoftSide magazine’s TRS-80 Software Exchange and a similar organ run by Creative Computing. When Scott Adams started Adventure International, he signed up there as well. (Occupying a weird ground somewhere between software publisher and catalog merchant, AI did not demand an exclusive license to the software they “published.”) Meanwhile he made a second game, Galactic Trader, which replaced military with economic conquest. By the end of 1979, the two games together were bringing in about $1000 per month.

That $1000 was very welcome, because otherwise the bottom was falling out for Doug financially. The second oil crisis precipitated by the Iranian Revolution had seriously damaged the economy, and Doug could no longer sell his houses. Meanwhile it was becoming increasingly clear that his country law practice was not sustainable on its own, at least not in this economy. Barely two years after coming to Maine, he decided to cut his losses and move on, yet again, to something else. With no clear plan as yet what that something would be, he piled into his old Chevy Impala along with his 220-pound mastiff (in the front seat) and his computer (in the back) to visit his little brother in Eugene, Oregon. The car started to die in eastern Oregon. Doug:

Something went out with the transmission. It started throwing out smoke. Fortunately, by the time I got into western Oregon it was mostly downhill to Eugene because I had the windows rolled down so we could breathe because the smoke was coming up through the transmission. I couldn’t go more than 15 miles an hour and the windshield wipers wouldn’t work and it was a blizzard outside. I was out there kind of working the wipers by hand going downhill. Finally, we got down into Pendleton, which was just a lot lower than Walla Walla, and we could see again. We made it to about five miles from Eugene when the car finally gave up and my brother came and got me.

Said brother, Gary Carlston, had also made an interesting life of it so far. Like Doug, Gary had gone to Harvard, where he had planned, largely on a whim, to major in Celtic Studies. However, that program was full. On the same floor were the offices for Scandinavian Studies. He knew that the Carlston family had originally come to the United States from Sweden, and like his brother he was fascinated by languages, so what the hell… six years later, he had a Master’s in Scandinavian Languages and Literature. In the midst of that, Gary decided to spend one summer holiday in, appropriately enough, Sweden. An accomplished basketball player and coach, he got into a pick-up game with some locals there. One thing led to another, and Gary found himself returning the following year for a gig that was, in Steven Levy’s words, “so desirable that grown men gasped when he mentioned it”: coaching a Swedish women’s basketball team. Gary himself would later say, “Most girls in Sweden don’t look like the tall model type you’d expect.” Pause… wait for it. “This team did, though.” Whatever its perks, he proved to be good at the fundamentals of his job, leading the team to three championships and two runners-up in five years.

With Harvard and basketball behind him, Gary was faced with making a living in the real world. He briefly taught Swedish in a summer program, but the language was hardly in huge demand in the United States. He worked for a year as a director of the March of Dimes charity in Eugene, but he hated it, and finally quit. That was in the summer of 1979. When brother Doug arrived for his visit, Gary had already spent six months fruitlessly looking for another permanent job while trying to bring in a little something selling reflectors to the parents of schoolchildren.

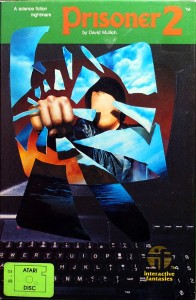

So, the two brothers, both completely broke, compared and contrasted their misfortune and wondered what the hell to do next. Then Doug, remembering the one thing that had been going pretty well for him lately, suggested that they start a real software publisher to sell his games instead of relying on the semi-professional distribution networks. The very non-computer-literate Gary allegedly replied, “What’s software?” He took some convincing, but, with no other prospects on the horizon, finally agreed. Brøderbund Software was officially founded on February 25, 1980, with $7000 the brothers were able to scrounge from their last savings and their family. As Doug later told Forbes magazine, the company was born at that place and moment only “because I was stuck without a car and didn’t have the money to buy a new one.”

The name “Brøderbund” itself is of course an odd one that would never pass muster with a corporate public-relations department today. It actually first appears in Doug’s very first game, Galactic Empire, where it’s the name of one of the warring factions. “Brøderbund” is a compound noun that is vaguely recognizable to speakers of a number of languages, but isn’t quite correct in any of them. In Danish and Norwegian, the word “brødre” is the plural of “bror,” which means “brother.” (The “ø” is a special vowel found only in Danish and Norwegian; it’s pronounced like the German “ö,” and, also like “ö,” is often used in plural forms of nouns.) It’s probably acceptable to change it to “brøder” in a compound word, to make pronunciation easier. However, the second part of the name, “bund,” is in no sense correct. The intended meaning is obviously the German “Bund,” meaning a bond or union. Yet in Danish or Norwegian the correct word would be “forbund”; “bund” alone means a ground or base, obviously not the intended meaning. So, what we have here is a mash-up of Danish and German — or an example of a sort of pidgin Danish, if you prefer.

Which is not to say that the Carlston brothers didn’t know exactly what they were doing in creating the name. Both were fascinated by languages, and enjoyed this sort of linguistic play. They chose to use the Danish and Norwegian word for “brother” in place of Gary’s more familiar Swedish because Swedish uses German-style umlauts; thus the word would have become “bröder.” The problem with “bröder” was that the “ö” would be impossible to represent on computer screens of the time. The “ø,” however, could be represented by simply typing a zero; then as (sometimes) now, computer displays used the slash to easily distinguish “0” from “o.” This also made the name a clever play on computer technology itself. Even in their professional copy, where the proper character would presumably have been available, the company would often write “Brøderbund” as “Br0derbund” to reinforce the computer connection. As for pronunciation… let’s not even get into that. Suffice to say that everyone just said the name as “Broderbund,” although that’s not correct if we insist on reading it as a Scandinavian word.

Linguistic issues aside, Brøderbund was not a stunning success in its early months. They did have three games to sell, in the form of Doug’s Galactic trilogy. (He had recently completed a third and final game in the series.) Yet, with Softsel yet to be founded, software distribution to retail was in a confused and uncertain state, and neither brother was naturally suited to cold-calling stores to try to sell them on their products. May of 1980 was the low point; it seems incredible, but Doug claims that sales for that entire month were exactly $0.00. Then two things happened that would begin to turn the company around.

At the very first trade show at which they exhibited, the West Coast Computer Faire of March 1980, the Carlstons had made the acquaintance of the Japanese software company Starcraft. In June, they got a call from them. As I mentioned in a recent post, Starcraft would later make a big name for itself within Japan by porting and translating Western games for the domestic market. At this point, however, they were reaching out to the West with a view to moving software in the other direction. They had coded several solid action games for the Apple II. Now they were looking for an American partner to sell them for them. This was a huge break, not only because the flashier Starcraft titles diversified Brøderbund’s portfolio greatly when contrasted with Doug’s more cerebral text-oriented strategy games, but also because these games ran on the Apple II, already a much more vibrant and healthy software platform than the Radio Shack-strangled TRS-80. From this point forward, Brøderbund would also switch their emphasis to the Apple II, porting the Galactic trilogy over and developing most of their new software for that platform first.

Shortly after the Starcraft deal was made, Gary got a call from his beloved old basketball colleagues from Sweden, saying they were coming to San Francisco and wanted to meet him there. When he told them that he didn’t have the money to come, they said they could pay for half of the trip — for a one-way ticket from Eugene to San Francisco. The brothers hatched a plan: Gary would fill his suitcase with software, then visit every computer store he could find in the Bay area, attempting to sell the stuff to them personally and hopefully earn enough to get home again. It worked beautifully; he sold almost $2000 worth of software. In the absence of a proper distribution network, the way forward was now clear: they must visit stores personally to sell the owners on their games. At the end of July, Doug took off on a zigzagging road trip to Boston and back, and sold some $15,000 worth of games on the way.

Still, it was a fairly time-consuming and expensive way of moving product, and times remained tight. Doug:

We were going weeks where we only ate on three days; things were that tight. We had used up all my savings from being an attorney and were maxed out on my credit card. My parents didn’t have any money. [In] October my mother lent us $2000 that she had inherited and her sister also lent us $2000.

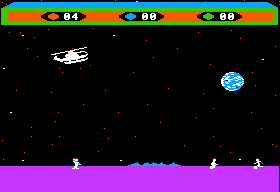

Then, near the end of the year, Starcraft gave them a goldmine in the form of Apple Galaxian, a perfect clone of a new hit arcade game from another Japanese company, Namco. Soon enough people would be getting sued over far less blatant copying, but it was, ironically given the company’s later reputation for integrity and innovation, this unabashed arcade ripoff that really established Brøderbund as a major player in the software industry. Doug claims today to have not even been aware at first that it was a facsimile of someone else’s game, as the game had just recently been introduced to North American arcades.

Critically, it was at just this point that Softsel, the first proper software distributor, arrived on the scene, making it much easier for Brøderbund and other companies to get their products into stores around the country without the necessity for personal meet-and-greets. Bob Leff of Softsel played a key, and very personal, role in Apple Galaxian‘s success. Doug:

When I sent him a copy of this new game, he said, “We love it, and I want 5000 copies right away.” And I told him, “I’d love to do it, but I don’t have 5000 disks, and I don’t have enough money to buy 5000 disks.” He said, “I’ll tell you what, I’ll lend you the money. You buy the disks and I’ll lend you the money as long as you send them all to me.” I said okay. And he sold everything within a month.

Brøderbund’s sales went from $10,000 in November of 1980 to $55,000 in December, all on the strength of Apple Galaxian. In fact, their sales for December amounted to more than those for the entire rest of the year. Apple Galaxian topped the Softalk magazine chart as the bestselling Apple II program in the country for three months. (Yes, it even outsold VisiCalc during that period.) With both Namco and, oddly, Apple themselves beginning to make legal rumbles, Brøderbund changed the name to Alien Rain in the spring of 1981, and it continued a bestseller for quite some months under its new moniker.

On the back of Apple Galaxian/Alien Rain, the Carlstons could begin to hire some employees and make bigger, more ambitious deals with a growing stable of outside developers. They brought in their younger sister Cathy, who had been unhappy in her job as a retail buyer for Lord and Taylor, to take the role of office manager. And they branched out into productivity software, for which they would soon become more famous than they were for their games. Bank Street Writer, an innovative word processor, was a particular hit, as was the first really complete payroll package to be released for PCs. In the summer of 1981, they left Eugene, which they felt was just too isolated and small to be conducive to their business and which had a horrible problem with fog that sometimes shut down the airport for a week or more at a time, for San Rafael, California, a town in the vicinity of San Francisco that was most famous for being the home of George Lucas and his production company Lucasfilm. In typically unpretentious fashion, they effected the move by renting three U-Haul trucks, packing everything up, and driving the lot down themselves.

You’ll have a hard time finding anyone who knew or worked with the Carlstons with much bad to say about them. For years the siblings each took a regular shift on Brøderbund’s production line, by all indications not as a gimmick but out of a real, heartfelt desire to demonstrate “the dignity in all of the work” at the company, and to have a chance to bond and really talk with their employees. Indeed, they found themselves caring more for their employees than any business guide would recommend, sometimes giving them a second chance even after they were caught stealing. Doug: “It turns out that Gary was the only person who could fire people — which is a valuable skill. He didn’t like it but he was able to do it.” Doug also demonstrated what would seem a hopelessly naive attitude toward his direct competitors. He called them all the “brotherhood,” and even wrote a book in 1985 (the long out-of-print Software People) to sing their praises. Somehow he and his siblings got rich in the cutthroat world of capitalism in the most subversive way imaginable: by just being really nice and fair to everyone, and never losing their idealism about the software they produced. Or anyway, that was most of it. As a story I’m about to retell will illustrate, there was a certain competitive edge to be found under their more cuddly qualities.

Everyone liked the Carlstons, but Brøderbund forged a special bond with On-Line Systems. Although the religious Carlston clan did not share the Williams’ taste for partying, the two companies were otherwise remarkably similar. Both were founded at almost the same time; both focused their early efforts on the Apple II; both enjoyed a relaxed internal culture unconcerned with rank or title; both published a diverse array of software, mostly from outside programmers, rather than specializing like, say, Infocom; both were headed by erstwhile hackers who found less and less time to write code as their businesses grew; both shared the conviction that they were doing something that really mattered for the future; both would ultimately prove to be long-term survivors and winners in a brutal industry, outliving virtually all of their other peers. Especially after making the move to San Rafael, the Williamses and the Carlstons saw quite a lot of one another, and shared more trade secrets than any MBA would recommend.

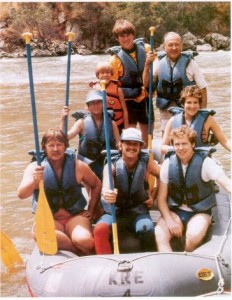

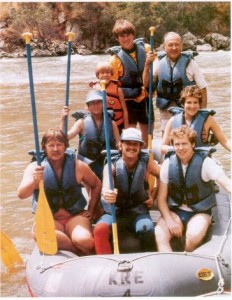

The Carlstons were naturally all invited on that On-Line-sponsored, era-defining whitewater-rafting trip in the summer of 1981. One evening on that trip Doug and Ken Williams seriously discussed merging their two companies, but ultimately decided that it wouldn’t make sense. Normally a company merges with another to get something it lacks, but their two companies were so similar that it was hard to see what that something could be, in the case of either — not to mention the stress of sorting out locations, product lines, management structures, etc. Most of all, it became pretty clear that neither Ken nor Doug was very interested in giving up any control of the company he had founded. Instead they would continue as unusually friendly competitors for more than 15 years.

Another incident from the trip shows why that may have been for the best. While drifting down the river, the group came to a spot where “the water was deep and smooth, and cliffs rose up above the river banks.” Ken shouted to stop the boats, so he and whoever else wanted to could climb up to the cliffs and dive off. Quite a large number, including Roberta and Doug and his sister Cathy, who had swum competitively, decided to join him. At the top, however, Ken got cold feet, even as others were taking the plunge. He begged Doug to go back down with him and Roberta, so they wouldn’t have to be the only chickens in the group. Doug said no, and, to encourage him, suggested that they all four hold hands and jump off together. Ken agreed, they joined hands and ran toward the edge — but Ken balked again. In the end he and Roberta climbed back down in shame, while Doug and Cathy made the leap. “I pushed myself a little further than I was ready to handle,” Ken said. They were all friends, Doug later wrote, “but we all like to win, and if the other falters, we aren’t likely to wait too long for him to catch up.” In his own quiet way Doug was as driven to win as the blustery Ken — or, as demonstrated by that moment on the top of the cliff, perhaps more so.

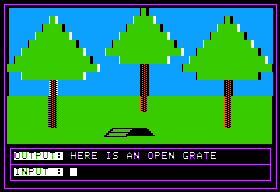

Brøderbund may have been having more and more success with their productivity software, but they were hardly ready to abandon games. Indeed, their action games were amongst the most popular and highly regarded on the Apple II. We’ll look at a particularly important title in their stable, released just about a year after the rafting adventure, next time.

(The early history of Brøderbund has been very well documented. The most useful sources for this article were: Steven Levy’s Hackers; Doug Carlston’s own Software People (out of print); the lengthy interview Doug Carlston conducted with The Computer History Museum in 2004; and a profile of the company in the September 1984 Creative Computing.)