One of the computers installed at Monthly ASCII‘s offices was a DEC PDP-11 minicomputer. Amongst other programs, this machine housed many of the games popular with Western institutional hackers of the early 1980s, such as Adventure and Zork. Many staffers played these games obsessively before and after working hours — and occasionally during them — in spite of the challenges their English language presented. ASCII also owned some imported Western PCs, along with early adventure games from Scott Adams, On-Line, and Infocom. With such games still unknown on homegrown Japanese machines, some staffers naturally began thinking about remedying that by writing a text adventure of their own. By this time various Western magazines had examined the technology used to develop professional text adventures. In addition to the many type-in BASIC adventures, there were articles like the one that appeared in Practical Computing in August of 1980, describing a machine-language text-adventure engine similar to the one used by Scott Adams.

With all this information at hand, two ASCII employees, Hideki Akiyama and Suguho Takahashi, proposed that the magazine develop and publish a text adventure for the 1982 Yearly Ah-SKI! parody issue. With permission granted, Akiyama developed an adventuring engine, and Takahashi wrote the first scenario for the system: Omotesando Adventure, after the street in Tokyo where ASCII‘s offices were located. It was a difficult project, particularly as both men could only work on it during down-time from their regular jobs on the magazine’s editorial staff. Still, as the first adventure made in Japan, both were determined that it should not be “shoddily made.” Omotesando was, in the words of Takahashi, a “pretty outrageous idea” for one reason in particular: despite being published in a Japanese magazine for a Japanese audience and running on Japanese computers, it was actually written in English.

Amongst the languages of the world, English, with its simple verb-object imperative construction, is rather unusually well-suited to a parser-driven adventure game. Even a related language like German makes coding a parser more complex through its many two-part verbs and its fondness for reflexive pronouns. Japanese, meanwhile, is still vastly less amenable to traditional parsing algorithms. As my translation and research partner for this article, Oren Ronen, told me, “Japanese doesn’t lend itself easily to the verb-noun pattern without sounding completely broken.” I suppose that ASCII could have had Omotesando Adventure output text in Japanese and accept input in English, but that would have created huge problems of its own, as legions of imperfect English speakers tried to figure out how to reference this or that Japanese word in the text in English. So, pure English it was — and luckily so for those of us who don’t know a lick of Japanese, as it gives us a chance to peek inside this important artifact.

Omotesando was developed on a Japanese Oki IF-800 computer running the English operating system CP/M. This machine was chosen because it wasn’t a particularly popular one with the other staffers, and thus normally spent its time gathering dust in a corner of ASCII‘s offices. When development was complete, Akiyama needed only write some bridge code for the various other Japanese Z80-based PCs, such as the very popular PC-8001 and PC-8801. With a little help from some other staffers, he soon had Omotesando running on a substantial percentage of Japanese PCs.

ASCII introduced Omotesando excitedly as a whole new experience for Japanese computer users:

Among the various things we can use a personal computer for, games are the most constant and popular. Games are in high demand, and software houses are pushing them into the market continuously. This issue we are introducing the Adventure Game. It’s an entirely new genre, the like of which was never seen on a computer. We may even call it a “New Type” of computer games.

The premise has you an employee of an unnamed rival magazine to ASCII. You’ve been ordered to sneak into ASCII‘s offices and find some way to sabotage the operation. It’s a nice change of pace from the dragons and spaceships that still dominated American text adventures, and there’s a certain postmodern sort of cleverness to all of the self-referentiality, a precursor to the generations of amateur bedroom text-adventure implementers who would get their start by implementing, well, their own bedrooms and/or apartments.

As one might expect, Omotesando is proudly old school in its design sensibilities.

Let’s state this clearly: we don’t believe you, who are experiencing an adventure for the first time, will be able to easily achieve the game’s goals. For several dozen tries you probably won’t even manage to sneak into ASCII Publishing’s offices. You will be caught in traps and die frustrating deaths. By trying again and again dozens or hundreds of times, you’ll learn things like “if I do this here I can go through” or “before I do this I must not do that” by trial and error and will be able to proceed. Solving the riddle that is the entire game can take several months and try your endurance.

In any case, since this is a game of endurance, we added the ability to save your position to a cassette and reload the game to continue from the same point. We’re very kind.

That said, to stay in the spirit of the adventure game, you must look for the way to save the game in the course of playing it (we’re not always kind). Once you find the way, you will be able to solve the game’s puzzles much more quickly.

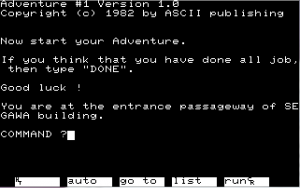

As the illustration above shows, the English of the game is far, far from perfect. The same quirky sense of humor that marks the Yearly Ah-SKI! editorial content is as present as the sharp limitations on text length will allow. There is also the unusual (and annoying) “feature” of having to LOOK every time you enter a new room to determine what is really there. Other than that, and of course its setting, there’s oddly little about Omotesando to separate it from its inspirations. Perhaps the most surprising thing about it is that it is quite technically and even artistically competent within its modest aspirations. If you’d like to experience it for yourself, I’ve prepared a little care package for you. It includes Omotesando packaged up with a Japanese PC-8001 emulator as a Windows executable, along with translations and originals of the magazine articles that accompanied it. Sorry to be so platform-specific this time. Given the trials and tribulations of Japanese, this was about the best I could do. I do believe it should also run fine under WINE.

Omotesando Adventure, then, marks the beginning of the text adventure’s brief, precarious existence in Japan. The following year’s Yearly Ah-SKI! brought another, more complex game, once again implemented in English. By that time a Japanese company called Starcraft had begun a project to translate some of the more popular American illustrated text adventures for the domestic market, including most of On-Line’s Hi-Res Adventure line (with the expected exception of the white elephant Time Zone). Still, the difficulty of parsing Japanese made these games an awkward fit for the country; some actually resorted to making the player type a Japanese verb, hit enter, and then input a noun as the least painful and grammatically ugly approach.

As an alternative to such kludges, amateurs and professionals alike soon began experimenting with menu-driven interfaces in place of parsers. Thus was born the tradition of the Japanese visual novel, which became extraordinarily popular in spite of or because of the fact that many were partly or entirely exercises in pornography. Whatever objections some might have to their subject matter, or frustrations with their limited scope for player choice, these games did at least depart definitively from text adventures’ obsessions with puzzles and low-level object interactions to focus on telling more complex stories at a less granular level than most of their peers in the West. In fact, visual novels and the related genre of dating simulations remain important to Japanese computing culture even today, decades after text adventures faded from store shelves in the West.

A much more successful Western genre in Japan in comparison to the text adventure was the CRPG. Wizardry and its sequels in particular were massively popular when translated into Japanese. Just as the Beatles and other British groups of the 1960s mirrored back to America the music that America had originally created, Japanese CRPGs eventually made their way back to the West, where their unique, heavily story-oriented sensibility made them more popular with many players than the more hardcore, stats-oriented Western games.

Indeed, I’m afraid this blog will necessarily have to view Japan mostly through the lens of the West, through the games that made it back to these shores in English translations. I don’t know any Japanese, you see, and, while Oren did amazing work to help me with this article, I can’t expect him to keep doing my research and translating huge chunks of material for me. So, take this article as primer only on what was going on inside a country that would soon become hugely important to Western gaming culture. But before I move on, I’ll leave you with one last historical curiosity from inside Japan that Oren dug up for us.

During the early 1990s, after parser-driven games were considered commercially dead not only in Japan but also in the West, four of Infocom’s classic titles were ported to Japanese computers, and translated into Japanese in the process. Let me just let Oren finish this story:

There were 4 translations: Zork 1 is the only one that’s mentioned anywhere on the western web, but that’s only because it got a strange console release on the PlayStation and Sega Saturn. Most references get the facts wrong by saying those were the only releases it got. In fact, there was also a PC release with a proper text-entry based parser. In addition, Enchanter, Planetfall and (of all things) Moonmist got translations. All were wrapped in a fancy, Zork Zero-like interface with a changing graphical background depending on your location, a clickable compass-rose, and menus for saving and loading the game. They were released in the early ’90s by a software company called SystemSoft that mostly did game localizations for the Japanese market. They all mention Activision in the documentation, so the deal was made after Infocom’s buyout. The translations themselves are pretty good, as far as my non-native literary appreciation skills can tell.

The most remarkable thing about them is that they are the best implementation I can find anywhere of an IF parser in Japanese. Because of the complexity of parsing Japanese text, adventure games moved to menu-based systems much faster than in the West, and the few parser-based games that were released either required input in English or did a no-frills two word Japanese parser that was completely ungrammatical. The Infocom games parse complete, grammatical Japanese sentences (which is, again, a much more difficult task than in English) and even do all the fancy Infocom tricks like “take all except the stone” and remembering context for pronouns. I’m quite amazed they went through all the effort several years after parser-based games were completely forgotten about in the country.

The translations even reproduced the feelies from the original American releases. Alas, it appears they were, unsurprisingly, not successful, and they mark the last gasp of the text adventure’s short and fitful life in Japan.

(My thanks again to Oren Ronen for all his help researching and translating for this article and the preceding one, which included translating a short interview with the designers of Omotesando Adventure.)