In an earlier post I described how the Zork Users Group was founded when Mike Dornbrook left Infocom’s Boston home for an MBA program at the University of Chicago, taking what essentially amounted to the company’s customer-relations division with him. ZUG was not alone. An entire aftermarket of companies dedicated to lending aid and comfort to players of other companies’ games was springing up around the same time, a sign of the health of the growing entertainment-software market even in the midst of an ugly recession. ZUG was unique, however, in having such a cozy relationship with Infocom. Many other publishers saw this burgeoning aftermarket as little better than parasites. Some of these attitudes were likely down to economic considerations; who wants to watch someone else sell hints you could be selling yourself? Others seem more down to control-freak tendencies and sheer bloody-mindedness. Luckily, ZUG didn’t have to deal with any of it.

Indeed, to say that ZUG had a privileged relationship with Infocom hardly begins to tell the story. Each Infocom game came with a card that the purchaser could send in to join ZUG. And not only did ZUG sell their own merchandise, but they also became official retailers of the Infocom games themselves, which they distributed through their catalogs along with all the other stuff. But, lest we get ahead of ourselves, let’s pick up the ZUG story from near the beginning.

Dornbrook’s initial plan for ZUG was to continue business as usual, sending out maps and hints from his new apartment in Chicago. However, without his erstwhile partner Steve Meretzky and with all the pressures of graduate school, that promised to be quite a challenge. Then, between leaving Boston and beginning his program in Chicago, Dornbrook spent a week with his parents at their home in Milwaukee. His father had just recently retired, and, seeing the problem, made a proposal: he could handle order fulfillment from the basement of the family home, leaving Mike free to answer hints and work on preparing new products from Chicago. Mike happily accepted, and so ZUG was officially established as a Milwaukee business. Mike’s mother also got involved as the mailing-list maintainer, which consisted at this time of about 1000 names and addresses on paper; as was still typical of these times, nothing about ZUG was computerized.

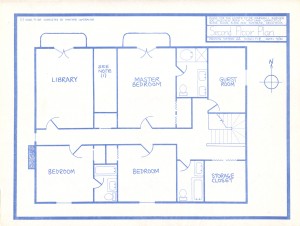

Once settled in Chicago, Dornbrook enlisted Meretzky to draw up a map for Zork II for sale alongside the existing Zork I map, and once again got his artist friend Dave Ardito to do the illustrations. In early 1982 Meretzky accepted an official job with Infocom as their first full-time play-tester. It was a perfect fit for his other gig as ZUG’s cartographer; he could know everything about the games’ geographies long before they were released. For the Deadline map, Meretzky drew upon his training as a construction manager, departing from the standard matrix of lines and rectangles to present the Robner estate as a set of architectural blueprints.

With a growing, hungry, and loyal Infocom fanbase to feed, ZUG also began branching out into unabashed novelty products. By the end of 1982 they were peddling not just games, maps, and hints, but also posters, tee-shirt iron-ons, bumper stickers, and buttons. In addition to sending out the order forms for their merchandise, they began a roughly quarterly newsletter to reach the fans and tell them about all the latest happenings in the worlds of ZUG and Infocom: The New Zork Times. I noted in an earlier post that much of what people remember as Infocom was really the work of their advertising firm, G/R Copy. Similarly, another big chunk of their public image was forged not in-house but rather by Dornbrook and friends through the auspices of ZUG.

Even as ZUG branched out in other directions, hints remained a constant thorn in Dornbrook’s side. As ZUG’s membership roles increased rapidly, he found it more and more difficult to keep delivering personalized responses to requests for hints on top of his studies and his other ZUG activities. He also found it increasingly dull, since most questions centered on the same handful of trouble spots. The obvious solution was to prepare some sort of standard hint booklet for sale, but he was loathe to do this, fearing it would be too easy for a player to spoil large swathes of the game for herself while looking for the answer to just one or two puzzles. Another, less idealistic concern was the knowledge that someone was certain to photocopy the hint booklets — or type them into their computer — and start passing them around as soon as he began to sell them. Yet it was also clear that manually dealing with hint requests would soon be not just impractical but impossible; if one thing looked obvious, it was that Infocom and ZUG were just beginning to take off. So, Dornbrook started looking for alternatives to a simple printed list of puzzle answers.

He considered using scratch-offs like are used for lottery tickets; offset-printed answers that could only be properly read through a pair of 3-D glasses; a little window that slid up and down the page, allowing the reader to only see a line or two at a time. Nothing proved practical. Then (from the extras DVD of Get Lamp):

I was at a party back in my home town with some friends of mine from high-school days. One of them had gone to pharmacy school at the University of Wisconsin. I was describing that I was trying to create these booklets, trying to come up with an answer. He said, “Why don’t you use invisible ink?”

One of the friend’s professors had used invisible ink for tests; students who didn’t know an answer right away could develop “invisible” hints by running a special marker over the appropriate part of the page, at a cost to their overall score. Dornbrook had actually worked in printing on and off over the years, but had never heard of such a thing. After calling everywhere he could think of to ask about the technology, only to have people think him “nuts,” he finally called the professor’s office directly. An assistant found the name of the company from which the professor sourced the stuff: A.B. Dick. They in turn put him in touch with a printer who had the technology, and InvisiClues were born. The first, written by Dornbrook for Zork I and illustrated as usual by Ardito, arrived in the spring of 1982.

Each InvisiClues booklet contained many questions about the game it covered. The user found the one that pertained to her, then developed the solution by running a special marker over the “invisible” answer. Each answer was itself presented as a series of graduated steps to be developed one at a time, from gentle nudge to the complete solution. Each booklet also included a fair number of dummy questions to further discourage readers from just developing and devouring random answers, as well as to obfuscate what was and was not in the game and thus prevent the reader from spoiling the experience just by reading the questions. If developed, these dummy questions chided the reader appropriately (and sarcastically).

InvisiClues was a ridiculously clever idea, although there were a couple of caveats. They were expensive to make and thus quite expensive to buy; while Adventure International was selling a “Book of Hints” for all twelve of the Scott Adams adventures for $8, an InvisiClues booklet for a single Infocom game would cost you considerably more than that. And, developed hints would begin to fade after about six months. Still, in spite of these disadvantages, InvisiClues were a tremendous hit. They were just fun in a way that the ciphers and look-up tables other companies used to disguise their own hints were not.

Infocom and ZUG’s commercial fortunes skyrocketed hand in hand. Infocom sold 100,000 games in 1982, up from 12,000 the year before. ZUG’s membership rolls, meanwhile, increased from 1000 at the start of the year to 4000 at its mid-point to over 10,000 by its end. Midway through the next year, they had 20,000 members. By this time they had finally computerized the operation (via an IBM PC with a then-exotic 10 MB hard drive), and had three other part-time employees in addition to Mike and his parents. Amusingly, other than Mike not a single one of them had ever played an Infocom game or had any interest in doing so.

There’s much more to say about Infocom’s 1982, but next we’ll travel half a world away to look at another, very different computing culture.