As 1982 dawned, Infocom had two hit games available in new, snazzy packaging under their own imprint along with a growing reputation for being the class of the adventure-game field. The future was looking pretty rosy. That January they moved from their tiny one-room office above Boston’s Faneuil Hall Marketplace to much larger accommodations on nearby Wheeler Street. So large, in fact, that they might have seemed like overkill, except that Infocom had big plans to become a major player in the growing software market. But right now they had just a few full-time employees to house there. One of these was Steve Meretzky, late of the Zork User’s Group, hired as Infocom’s first full-time tester shortly after the move. A much larger crew of part-timers and moonlighters cycled in and out at all hours.

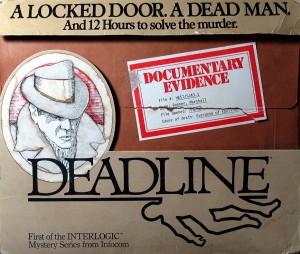

It’s fascinating from the perspective of today to watch as the pieces of the Infocom that so many of us remember and love fall into place one by one. By early 1982 they already had their classic logo and text style, their professional but also friendly and easygoing editorial voice, and their distinctive Zork packaging iconography. As Jason Scott has pointed out, the unsung hero through this process was the advertising agency that Mort Rosenthal hooked Infocom up with during his brief stay with the company: Giardini/Russell — or, more easily, G/R Copy. G/R’s role went far beyond just crafting the occasional magazine ad. They were intimately involved with virtually every aspect of the Infocom experience that wasn’t contained on the actual disks, suggesting and crafting the packaging and the feelies contained therein, even writing large swathes of the instruction manuals. They even named a surprising number of the games, including Deadline, the one I’m going to be talking about today; it bore the much less compelling name Was It Murder? before G/R got a hold of it. Scott puts it succinctly: “A lot of what people think of as ‘Infocom’ is in fact Giardini/Russell.” It’s a classic example of creative, artistic image-crafting that can stand alongside such iconic campaigns as the work that Arnold Worldwide did for Volkswagen around the millennium. Infocom were lucky to have them, and smart enough to give them freedom to work their magic. G/R are the main reason why, even today, Infocom’s games and advertising look so fresh and enticing.

Still, in early 1982 major parts of the final Infocom puzzle were still missing. Most notably, they still hadn’t decided what to call the games, not being comfortable with “text adventures” but having not yet come up with the label “interactive fiction.” The long-term ambition of Al Vezza and at least some of the other founders remained to use games as an eventual sideline, a springboard into the lucrative business software market that was now growing like crazy in the wake of the IBM PC’s introduction. In that light, it felt important to distinguish the games line from the company’s identity as a whole. For now, they could only come up with the rather tepid designation of “InterLogic Adventures,” apparently imagining InterLogic becoming a subsidiary brand within the Infocom empire. In the end, it would be a blessedly short-lived name.

Whatever they called their games, Marc Blank, now with the newly minted title of Vice-President for Product Development, was still showing a restless determination to try new things with them. Having written much of the original Zork, designed and endlessly polished the famed Infocom parser, and then come up with the concept and design of the Z-Machine, he was now working on what would prove to be the most significant leap forward for digital ludic narrative since Zork‘s debut on the micros. It started when one or two of the Dennis Wheatley crime dossier reprints came his way. Blank found the idea of solving a crime yourself, of playing a detective in your own mystery story, to be very compelling. And of course it was a natural choice for a text adventure, perhaps a more natural fit than a fantasy romp. After all, and as I described recently, classic mystery novels were really games dressed up as stories. All he had to do was what Wheatley and Links had done, to make the implicit explicit. But by doing that on a computer he could create something much more interactive than the crime dossiers, with their piles of static clues to read to come to a single conclusion at the end of it all. No, on the computer the player would be able to guide every step of the investigation for herself — to really play the detective. He spent the latter months of 1981 and the early weeks of 1982 crafting the game that would become Deadline, “first of the InterLogic Mystery Series from Infocom.”

There were other mysteries of a sort already available on computers — titles such as Jyym Pearson’s Curse of Crowley Manor (published by Scott Adams’s Adventure International as part of their OtherVentures line) and of course Ken and Roberta Williams’s debut, Mystery House. But, while these games included the trappings of mystery, their puzzles and gameplay mark them as standard text adventures, a collection of unrelated, static puzzles; they were Adventure in mystery clothing. Blank was envisioning a work where, just like in a classic detective novel, the story itself is the puzzle. Let me take just a moment to try to make clear what I’m getting at here.

While writing about Time Zone, Carl Muckenhoupt noted how separated each zone in that game is from all the others, then leaped to this:

Maybe it’s just that the author was used to thinking in terms of local effects, because that’s how early adventure games generally worked. The whole idea of non-local effects was a major leap in sophistication for adventure games, arguably more significant than the full-sentence parser.

Let’s run a little bit further with that.

It’s true that all adventure games at some level are, as Zork put it, “self-contained and self-maintaining universes.” Yet adventures prior to Deadline had been curiously static universes. Annoyances like Adventure‘s dwarfs and Zork‘s thief aside, their designers thought only in terms of local interactions. And, expiring light sources aside, they thought not at all about the passage of time. Early text adventures have environments to explore and (static) problems to solve, but they only occasionally and sporadically contain any sense of plotting, at best limited to an end game that triggers when the player has collected all the treasures or otherwise accomplished most of her goals. Blank, however, proposed to immerse the player in a real story, filled with other characters moving about with agendas of their own, with a plot arc rising to a real climax, and with — necessarily for the preceding to work — realistic passage of time culminating in the deadline from which the game drew its name. Scott Adams’s The Count had done some of this way back in 1979, but it had been inevitably limited by Adams’s primitive engine and the need to fit everything into 16 K of memory. Armed with Infocom’s superior technology, Blank now wanted to do it right. For the first time, the player of Deadline would have to act locally but think globally.

Just to make this very important idea absolutely clear, I’m going to quote at some length from an interview that Blank gave to SoftSide magazine in 1983. It shows that he knew exactly what he was doing in trying to create a new model for adventure games that would let them truly work as stories.

I think the elements of characters, interaction, and time flow are what make an adventure more like a story. Time flow is the critical one. In Zork I, the situation is static — you’re walking around in an effectively dead place. You find these problems and you try to solve them. If you can’t, you go on to some other problem and come back to it later. Nothing’s changed because very little is going on. Deadline, on the other hand, is much more like a story. Things happen at a certain time. The phone rings sometime around nine o’clock. You could pick it up, you could be some other place when it rings, or you could wait to see if someone else picks it up. What you can’t you do is hear the conversation at ten o’clock, because it happened at nine. Because of this event, the story changes — in other words, you’ve left that section of the story and moved on. There are some things you can’t go back to and they are usually time-related.

In a way it is like a novel. In fact, you’re drawn along with the course of things. You can’t just sit. The world is passing you by.

And the story changes. The difference between this and a traditional story is that the story changes, depending on what you do. If you walk into the Robner house and wait in the foyer until seven o’clock, you’ll see people coming and going. People talk to you, the phone rings, and at the end of the day someone comes to you and says you didn’t solve the case. Too bad. The whole story happened. The same thing is not true in Zork.

I won’t go so far as to say that it’s impossible to create an artistically compelling adventure in which the player merely wanders through a deserted environment. There are quite a lot of adventures which do succeed ludically and aesthetically within those constraints. Yet, if that is all that adventures can do, they must be a very limited and specific art form indeed. For adventures to be viable as a new form of literature (something Infocom would soon be talking about more and more), they needed to take this step — even though, as soon as they do, life must inevitably become a whole lot more complicated for the poor souls trying to design them.

Indeed, the sheer difficulty of the task in the face of the still absurdly limited technology at hand was the main reason that no one had created a more dynamic, story-driven adventure before. Even leaving aside the more advanced world-modeling that would be needed, telling a real story would require a lot more text than the bare stubs of descriptions that had previously sufficed. Given the limited disk and memory capacities of contemporary computers, that was a huge problem. Infocom’s Z-Machine was the most advanced microcomputer adventure engine in the world, but even it allowed, when stretched to the very limit, perhaps 35,000 words of text, about the equivalent of a novella. And in a way this figure is even less than it seems, as it must allow for blind alleys and utilitarian responses that a printed novella doesn’t. Looking at the problem, Blank hit upon a solution that would change not only Infocom but the whole industry. It once again came from Dennis Wheatley and J.G. Links.

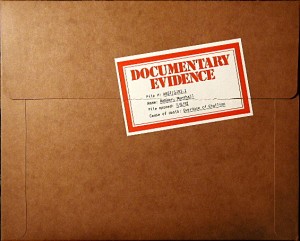

Those crime dossiers are, as I described in my last post, packed with documents and assorted physical “feelies” that describe the case the reader is attempting to solve. A certain portion of this information is effectively backstory, setting up the suspects, the crime, and the scenery before the investigation really begins in earnest. For his computer mystery, Blank realized that he could also move this information off the disk and onto paper. Through interviews with each of the possible suspects conducted by an out-of-game previous investigator, he could establish all the details of the crime as well as the general character of each suspect and her alibi. He could also include coroner and lab reports about the crime. Doing this would leave much more space on the disk for the stuff that really needed to be presented interactively. There were also a couple of other advantages to be had.

Piracy was, then as now, a constant thorn in the side of publishers. By moving all of this essential information out of the game proper, Infocom would make it unsolvable for anyone who just copied the disk. It was of course still possible to make copies of the extra goodies, but this was neither as convenient nor as cheap as it would be today. And there was no practical way in 1982 of preserving the documents digitally for transfer over the pirate BBS networks, short of retyping them all by hand.

Less cynically, the idea of giving the player her own little crime dossier was just plain cool. Working as always with G/R Copy, Blank and Infocom went all out. They packaged everything within an “evidence folder.”

Inside were the disk, the manual, and all of the documents related to the crime, along with a final fun little addition: a few of the pills that the victim had allegedly used to commit suicide. (Shades of The Malinsay Massacre…) Designing and fabricating all of this wasn’t cheap; in fact, it was the reason Infocom charged $10 more for Deadline than they had for their previous two games. But people loved it. Deadline heralded the beginning of a new era of similarly innovative computer-game packaging: cloth maps, physical props, novellas and novels, gate-fold boxes, lengthy and elaborate manuals. All of this stuff would soon be making the actual disks look like afterthoughts. A far cry indeed from the Ziploc baggies stuffed with hand-copied tapes and perhaps a mimeographed sheet of instructions of just a few years before.

Having dispensed with the externals, we’ll dive into Deadline the game next time.