There are some successful writers who are, as Ben Jonson wrote of Shakespeare, “not of an age but for all time.” But there are many more who become rich and famous in their own time only to be forgotten by later generations — or, if and when recalled by academics and diehards, remembered not for their continuing resonance but as curiosities, clues to understanding those strange people who lived all those years ago. Dennis Wheatley, for four decades one of the most bankable bestsellers in the book trade, belongs to this category. Upon his death in 1977, the vast majority of his immense oeuvre went almost immediately out of print even in his native Britain, and that was pretty much that for a fellow whose books even while he was still writing them had begun to seem painfully out of joint with the times.

To modern sensibilities, Wheatley’s life story is perhaps more interesting than his fiction. Born the son of an increasingly prosperous middle-class wine merchant in 1897, he was groomed virtually from birth to take over the business from his father when the time came. In that spirit, he received a respectable if not exceptional English public-school education. Indeed, “respectable but not exceptional” is a good way to describe the young Wheatley. Thanks to his family’s growing influence, he was able to finagle an officer’s billet in World War I and, even more importantly, to get himself posted to an artillery unit rather than the meat-grinder that was the infantry. Thus Wheatley had a comparatively easy war of it, in which, in the words of his biographer Phil Baker, “he did his duty; no less, if no more.” With that behind him, Wheatley, desperately class-conscious in the way that only one of somewhat uncertain status himself (in this case the son of a tradesman) could be, devoted himself to climbing society’s ranks while dabbling just enough in the business to keep his father soothed.

In 1927 his father died, leaving Wheatley in sole charge of the business. Unfortunately, thanks to the Great Depression that arrived a couple of years later and perhaps also to Wheatley’s decision to refocus the business on selling only very expensive wines and liquors to the most exclusive social sets, things started to go badly. Soon Wheatley, now entering his mid-30s, was forced to sell the failing business before it collapsed entirely. Worse, the purchasers upon examining the books began to speak of irregularities with regard to the money that Wheatley personally had taken out of the business. Soon they were threatening legal action in criminal court, and Wheatley was contemplating the prospect of jail time in addition to destitution. This man who had for 35 years been exactly what you would expect him to be now made the one really unexpected, audacious decision of his life. Despite having only his boyhood love of adventure novels and some earlier, unpublished and halfhearted stabs at fiction to his credit, he would write his way out of his financial straits. And so, in 1933, Dennis Wheatley the novelist was born.

In a great bit of damning with faint praise, Baker notes that Wheatley turned out to be only “good at writing books, after a fashion,” but “extremely good at selling them.” The critics, or at least those who didn’t lunch with him at one of his clubs, delighted in eviscerating him, and for many good reasons. His prose was remarkably awful, his characters paper-thin, his politics reactionary. Wheatley was a thoroughgoing manichean. People are either Good (Tories, businessmen, military men, the aristocracy, fascists in the early years) or Evil (communists, socialists, labor, Satanists, fascists after appeasement went out of fashion amongst the British Right, still later hippies and civil-rights activists). As time went on all of these latter groups started to blend into one overarching conspiracy of Evil in his books, communists walking hand in hand with Satanists. Wheatley does not allow the possibility of equally well-meaning people who simply disagree about means as opposed to ends. There is only Good and Evil, the former usually handsome or beautiful, the latter ugly. Subtle Wheatley ain’t.

For all his failings, however, Wheatley did have a flair for exciting plotting. He knew how to layer on the unexpected twists and turns, to get his heroes in and out of jam after jam by the skin of their teeth, each more dangerous and improbable than the last. For readers who shared his politics, and probably even a fair number of guilty-pleasure seekers who did not, his books were reliable comfort reads. To his credit, he never claimed them to be anything more. He replied to bad reviews with a bemused shrug, saying that he had “no pretensions to literary merit”; was “better aware than most of my shortcomings where fine English is concerned.” And anyway, he said, reading his books was at least better than going to the cinema, which was what his customers would otherwise do.

Wheatley took his customers’ wishes very, very seriously. Some of his books ended with a questionnaire, asking what they had thought of the book and what they would like to see in the next: what setting, which of his cast of recurring heroes and villains, even what percentage should be devoted to romance. Apropos this last: one other key to Wheatley’s success was his inclusion of a love story in each novel. This was thought to attract women readers — and, it must be said, he did sell far more books to women than did other writers in the traditionally male-dominated genres of thrillers and adventure stories. Wheatley wrote quickly, ensuring his fans were never kept waiting long for new material. In 1933, his first year as a working writer, he churned out an incredible three novels as well as one nonfiction book (on King Charles II of England, his personal hero) to buy himself out of his legal difficulties. After that outburst he settled into the only slightly more sedate pace of two novels per year, year after year.

But, you might be wondering, what does this fellow have to do with videogames? More than you might expect, actually. Wheatley, despite being very much a character of a different era than my usual concerns on this blog, is nevertheless important to them in two ways. One is somewhat tangential and one surprisingly direct. Let’s talk about the former today.

On Halloween, 1934, The Daily Mail began publishing a new Wheatley novel in serial form. It was called The Devil Rides Out, and concerned a cabal of Satan worshipers out to plunge the world into an at-the-time-still-hypothetical World War II by stirring up opposition to Hitler’s new Nazi regime. There are parts of the book that read just horribly wrong today. The heroes’ talisman of good, for instance, which when hung around the neck functions to protect them against the Satanists much as does garlic against vampires, is a swastika, “the oldest symbol of wisdom and right thinking in the world.” Despite — or perhaps because of — stuff like this, it’s become a kitschy classic of sorts today, the book most of the few who do bother to read Wheatley begin with — and, one suspects, usually end with.

In its own time, Devil became a sensation. Wheatley had been successful before, but Devil took him to a whole new level of fortune and fame, as Britain’s foremost popular pundit on all things occult. The book was in fact broadly if shallowly researched. Wheatley cultivated relationships with such figures as Montague Summers, a loathsome old reprobate of a priest who was convinced that witches in the medieval tradition remained a clear and present danger; and even an aging and ever more ridiculous Aleister Crowley, whose name still left many people in terror for their immortal soul but who in person was more likely to ask to borrow a fiver to feed his various addictions than anything more threatening. Crowley, Summers and a handful of other similarly dissipated, over-privileged Edwardians with too much time on their hands had in the decades before his book been largely responsible for reviving the notion of the occult, previously thought banished to the Middle Ages where it belonged, as an at least theoretically vital force again.

The problem with Satanism, at least from a certain point of view, is that there’s just not a whole lot of there there. Our perception of it through the ages is not down to any actual evidence from Satanists themselves, who seem to have barely existed if at all, but rather the fever dreams of those on the side of Good who claim to be desperate to stamp it out. From the Malleus Maleficarum down to the works of Summers, the scholarship on Satanism and witchcraft consists entirely of what the Good side of the hypothetical debate speculated that those on the side of Evil must be doing. The entire scholarly edifice is built on sand. Wheatley based much of the detail in Devil on Summers, who drew from the Malleus Maleficarum, which drew from… what? The whole is a chain of conjecture and imaginings (and, one suspects, fantasizing) of what a genuine cult of Satanists must be like if anyone ever met one. Direct experience is entirely absent. As we’re about to see, Wheatley just added another link to that chain.

As already described, Wheatley was always eager to give his public exactly what they wanted. And what they wanted, judging from sales of The Devil Rides Out and the excitement it generated, was more novels about Satanism and the occult. And so for the remainder of his life, interspersed with his tremendous output of other novels, he continued to churn them out. He also continued to cultivate his persona as “Britain’s occult uncle,” one on the side of Good who nevertheless had access to Dark Secrets that could be dangerous to lesser men. And he continued the bizarre, and increasingly ridiculous, practice of mixing worldly politics with spiritual struggle as he aged and the world around him agreed less and less with his traditionalist Tory values. “Is it possible that riots, wildcat strikes, anti-apartheid demonstrations and the appalling increase in crime have any connection with magic and Satanism?” he asked in 1971. The answer, as far as he was concerned, was a quite definite yes. He even advocated for a reinstatement of Britain’s anti-witchcraft laws, despite the last of them having only recently been taken off the books. Late in his life Wheatley almost seemed to morph into the now-deceased Montague Summers. He published a non-fiction treatise of his own, The Devil and All His Works, and sponsored the “Dennis Wheatley Library of the Occult,” a series of paperback editions that ranged from classic literature (Stoker’s Dracula, Goethe’s Faust) to the ramblings of Crowley and his ilk.

It’s hard to say to what extent Wheatley really believed this nonsense. He loved to sell books, and, while his books on other subjects were very successful, this stuff sold a whole order of magnitude better. It’s hard to understand why, if he thought Satanism a genuine danger to society, he continued to make it sound so damn appealing to so many of his readers via his novels, all of which featured a nubile, naked young virgin almost deflowered on an altar of Satan or similarly charged mixtures of black magic, sex, and sadism. Readers were not clucking over them as warnings about the spiritual dangers around them; no, they were getting off on the stuff. Wheatley therefore shouldn’t have been surprised when one of the elements of modern culture he hated most, a rock band, drew from his work — or, rather, pretty much blatantly ripped him off.

The band in question, Coven, was the first to really cement the link between Satanism and rock and roll. They were, however, far from one of the more talented bands to be accused of witchcraft. Their first album, the ponderously titled Witchcraft Destroys and Reaps Souls (1969), was a very contrived affair, largely the brainchild not of the band (who frankly don’t strike me as the brightest sorts) but of the producer, Bill Traut. He hired an outside songwriter, James Vincent, to put most of the album together:

“Bill brought me a large box full of books about witchcraft and related subjects. He told me to read them and start writing some songs … Sometime before the sun came up, I had completely written all the material requested of me for the entire album.”

It is, as you might imagine from a gestation like that, pretty dire stuff, like Jefferson Airplane with less impressive instrumentalists and very generic songs (apart from the EEEVVVVIIILLLL lyrics, of course). The most interesting track is not a song at all, but rather the 13-minute recording of an allegedly “authentic” Black Mass that concludes the album.

I have to put “authentic” in quotes in the context of a Black Mass because it’s very debatable whether there is such a thing. All evidence would seem to indicate that the Black Mass is not an ancient, timeless ritual, but an invention of the twentieth century. Further, it seems that none other than Wheatley’s erstwhile mentor Montague Summers may have been the man who invented it. Before suffering a spiritual “shock” that led him to God, Summers was himself a budding Satanist, one of the community of occult dabblers that swirled around Aleister Crowley. In his superb Lure of the Sinister, Gareth Medway accords a ritual conducted by Summers at his home in 1918 as “the earliest Black Mass for which there is reliable evidence.” Indeed, the younger Summers was quite a piece of work. A recollection from this era given by an acquaintance, from Baker’s Wheatley biography:

James was not invited to the Black Mass again, but he continued to see Summers socially: heavily made up and perfumed, drunk on liqueurs, Summers would cruise the London streets in search of young men. One day Summers confided his particular taste: “He was aroused only by devout young Catholics, their subsequent corruption giving him inexhaustible pleasure.”

There is evil here, but its source is not the supernatural entities the later Summers was so eager to stamp out.

So, we now have the older Summers feverishly describing and condemning the “ancient” ritual of the Black Mass which he himself likely invented as a younger man. Next, inevitably, we have Wheatley putting all of the “authentic” details into his novels. And then… then along comes Coven. Their recorded Black Mass is hilarious in its own right; for starters, the priest of Satan serving as master of ceremonies has the stentorian voice of a radio DJ, a far cry from the Voice of Evil one might expect. It gets even funnier, however, when you realize that virtually the entire ritual is plagiarized from one of Wheatley’s novels, The Satanist (1960).

The Coven album generated just the sort of controversy it had been intended to provoke. More so, actually; the outcry was so extreme that their record company pulled the album from shelves entirely in fairly short order. Thus in this case the real object of the endeavor, which was (in common with so much of the Satan industry) to make lots of money off cheap sensationalism, didn’t quite pan out. However, other bands, particularly in the emerging genre of heavy metal, now began dabbling in occult subject matter, most notably Black Sabbath. (In an odd coincidence, Coven’s bassist was named Oz Osbourne and the first song on their album was called “Black Sabbath.”) Most of these bands simply wrote about Satanism and the occult — with the usual dodgy research — rather than claiming to be full-on devil worshipers. Mostly it was all just silly fun perfect for teenage boys, and some of it was even pretty good; I’m still known to spin the occasional Iron Maiden. Yet it caused a firestorm of fear and anger from conservative Christians and orthodox Establishment-types who imagined their headbanging children being seduced to Satan through this music. What went unnoticed and unremarked, of course, was that the real source of most of the Satanic tropes they condemned was a man who was in a very real sense one of their own, Dennis Wheatley. One can make a pretty strong case that Wheatley essentially invented Satanism as it has existed in the popular imagination of the last 50 years — not a bad legacy for an otherwise forgotten author.

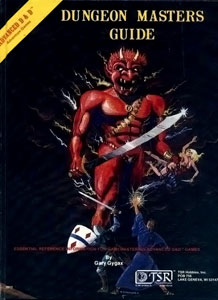

So, let’s see if we can bring this around to games at last, by looking at the urtext of ludic narrative, Dungeons and Dragons. There’s actually very little occult influence in the original edition of the game. It was, as I described in an earlier post, a product of dedicated wargamers with an interest in fantasy literature; there was nary an occultist among them. Later sourcebooks would begin to introduce somewhat generic devils and demons, and even to outline entire religious pantheons via the Deities and Demigods tome, but TSR was smart enough to stay well clear of any sort of obviously Christian mythos; certainly you won’t find stats for Satan in any of the Dungeons & Dragons rule books. Still, demons and devils and other horrors were in the game, as were spells. Many apparently found these elements hard to place outside of a Christian context. Nor was the artwork always helpful; in a picture, an evil efreeti from the Elemental Plane of Fire and Satan look pretty much the same.

Further, there was a substantial crossover between the kids listening to all this allegedly Satanic heavy-metal music and those playing D&D. While the lure of the forbidden (i.e., Satanism) was certainly part of heavy metal’s appeal, it also gave them grand themes of heroism and villainy, fantasy and history — all just the thing for teenagers looking for an escape from the trials and tribulations of high school. D&D, of course, gave them some of the same things. When concerned elders worried over the lurid heavy-metal posters on Junior’s bedroom walls, then saw that he was also playing this odd game of imagination full of spells and devils, and with similarly lurid artwork… well, it wasn’t a difficult leap to make. D&D and heavy metal must be the new face of Satanism — which, as we have seen and although no one seemed to realize it, didn’t actually have an old face.

The wrath of these crusaders would largely come down on D&D the tabletop RPG, as opposed to its computerized descendents that I’ve been writing about on this blog. Yet even they would not be immune. Richard Garriott received plenty of outraged letters accusing him of being an ambassador of Satan, particularly after Ultima III came out with its particularly Satanic-looking figure on the cover.

All of this controversy ended up playing a significant role in Garriott’s work as well as that of others, and I’ll be returning to it again in the future. However, I don’t want to move too far afield from Wheatley himself at just this moment. You see, he had yet another, completely different role to play in the field — in fact, the one I teased you with in my last post. We’ll pick that up again at last next time.