In January of 1981, as On-Line Systems were settling into their first office in Coarsegold, California, Roberta Williams already had three Hi-Res Adventures to her credit: Mystery House, The Wizard and the Princess, and the introductory adventure Mission: Asteroid. For her next game, she wanted to do something bold and big. Really big. She envisioned the ultimate treasure hunt, through time as well as space, in which the player would have to visit every continent at five different meticulously recreated historical moments, en route to a climax set on an alien planet in the far future that would by itself be larger than most standalone adventures.

When not working with Ken to get On-Line properly off the ground as a real business over the next six months, Roberta developed her idea, deciding exactly when and where should be included and sketching out maps and a puzzle structure as well as a simple framing story to justify it all. She had been so fascinated when first playing the original Adventure that she had “never wanted it to end.” Now, she seemed determined to get as close as possible to that ideal of infinite adventure. Time Zone just kept growing; by the time Roberta set the complete design document before Ken that summer, it had grown from an estimated five or six to twelve disk sides. This at a time when the biggest epics like Ultima and Wizardry were just spilling onto a second side for the first time.

Ken and Roberta had worked closely together on her first three games, with Roberta doing the writing and design and drawing the graphics and Ken coding it all on the computer. Now, however, Ken was busy running the full-fledged company that On-Line Systems had become. Anyway, Time Zone was far too ambitious a project for just two people to tackle. So Ken assembled a team of about ten people for Time Zone, who would spend months working full-time or part-time on the game. The formation of what Ken dubbed “the Time Zone task force” marks a significant moment in the history of game development.

Previously games had been created by one or at most two or three people, each a jack-of-all-trades doing the art, design, and programming as needed. This was after all an era when much game design revolved around exploiting some technical quirk or capability of the hosting hardware, leaving precious little space between the abstracts of design and the details of implementation. Roberta Williams, who as a non-programmer as well as a female was very much the odd woman out in early 1980s game development, felt the need in a contemporary interview for Computer Gaming World to defend her contribution as a pure designer: “Sometimes I feel that people don’t think that I’m as much a part of the creative process as I claim, due to the fact that I don’t program. The designing of the game is the most important and creative part of the project (and also the most fun).” In explicitly separating programmers from artists from designers for the Time Zone project, Ken and Roberta began the march toward the modern model of big-studio development, in which the jack-of-all-trades mastermind has been superseded by teams of hundreds of specialists weaving ever more granular fragments of the whole tapestry. It seems safe to say that Time Zone‘s team was the largest ever assembled to that point to create a computer game — fittingly, as Time Zone was the closest game development got in 1981 to a modern AAA title.

Time Zone was of course to be a Hi-Res Adventure, meaning its appeal would be rooted in the pictures that would illustrate each of its locations. Arguably the most important person on the team after Roberta herself therefore became Terry Pierce, an 18-year old hired straight out of the local high school to draw 1400 pictures for the game in pencil on graph paper. Two others then laboriously traced the pictures on Apple’s Graphics Tablet, filled them in with color, and stored them on disk in a highly compressed format, all accomplished with the tools Ken had originally developed for The Wizard and the Princess. The other side of the operation was the “logistics team,” a few scripters who translated Roberta’s descriptions of geography and puzzles into Ken’s ADL (Adventure Design Language). They created each of Roberta’s “time zones” as a small, self-contained adventure game in its own right. In ostensible charge of the whole was Bob Davis, the personable fellow Ken had hired out of a local liquor store. Yes, in a career trajectory that could only have happened in 1981 and possibly only in the Oakhurst area, Davis had gone from liquor-store clerk to designer of his own game (Ulysses and the Golden Fleece, Hi-Res Adventure #4) to manager of the most ambitious game-development effort in computer history, all in a matter of months. In between finishing up his own game, he now tinkered with ADL for Time Zone and loosely supervised the other coders and artists.

As you might imagine, the whole project started to go off the rails pretty quickly. Davis was well liked by everyone — he was a guy with “a huge heart and a ton of enthusiasm” in John Williams’s words — but lacked the experience or temperament to be a project manager. And while he was adept enough with simple ADL scripting, he lacked the technical acumen needed to even come up with a plan for pulling together all of these little games his coders were creating into the monstrous whole that would be Time Zone. Meanwhile Ken, the one guy at On-Line with the technical know-how and organizational smarts to really manage the project, was kept so busy by other concerns that he could spare little attention. Still, he expected Davis and his team to deliver a completed Time Zone before Christmas — an impossible deadline even without all of the partying and other distractions that accompanied life at On-Line.

Then a savior of sorts walked through the door, in the form of one Jeff Stephenson. At 30 years old, Stephenson already had considerable experience in the computer industry, as well as the sort of rigorous understanding of the technology and the organizational skills that most of the self-taught hackers and kids around On-Line lacked. His last employer had been none other than Software Arts, developers of the most important microcomputer application in the world, VisiCalc. Upon moving from Cambridge, Massachusetts, to the mountains of northern California, Stephenson decided to drop in on On-Line, the closest technology company, to see if they needed a programmer. From Hackers:

He put on cord jeans and a sport shirt for the interview; his wife suggested he dress up more. “This is the mountains,” Jeff reminded her, and drove down Deadwood Mountain to On-Line Systems. When he arrived, Ken told him, “I don’t know if you’re going to fit in here — you look kind of conservative.” He hired Jeff anyway, for $18,000 a year — $11,000 less than he’d been making at Software Arts.

Stephenson’s first assignment was to join Davis as co-head of the Time Zone project, to cut through the chaos and get the project back on track. His “conservatism” turned out to be exactly what Time Zone needed. He set everyone firmly and clearly about their appointed tasks, like would have been expected within the more businesslike confines of Software Arts. He himself made modifications to Ken’s Hi-Res Adventure engine to let them tie all of the regions in the game together, at least loosely, letting the player move her avatar from mini-adventure to mini-adventure via the time machine and to carry items with her. And he convinced another On-Line programmer, an action-game maestro named Warren Schwader, to dramatically speed up the rendering of the graphics as the player moved through this huge world. That made a game that would be, as we’ll see in my next post, very painful to play at least a modicum less painful.

By this point the focus for everyone had long ago shifted from Roberta’s original starry-eyed dream of an adventure game for (literally!) the ages to just getting the damn thing done in some reasonably acceptable form. Roberta would later say in the CGW interview, “Once we got into it and saw how big of a job it was, we were almost sorry we started it in the first place.” It’s probably safe to say that most of her team would have happily removed the “almost” from that statement. What with the time constraints, they created essentially a skeleton of Roberta’s vision, with the historical vignettes given little more atmosphere or detail than were needed to support the simple overarching puzzle structure.

Still, all those pictures remained to be drawn, bringing an unbelievable burden of work down on Terry Pierce’s thin shoulders. Almost as burdensome as the quantity of work was the sheer tedium of the subject matter: hundreds and hundreds of uninteresting “fields,” “forests,” and “city streets” to accompany the few locations with something to actually do or look at in each region. In what seems a case of bizarrely misplaced priorities today, the Hi-Res Adventure brand demanded that every single one of Time Zone‘s more than 1300 locations be given its own unique picture, even if the location itself consisted of only “You are in a forest.” Ken and Roberta knew perfectly well where their bread was buttered. Hi-Res Adventures didn’t sell so well because of deathless prose or intricate world-modeling; they advanced little beyond the Scott Adams games in these areas. No, they sold so well because of all those colorful pictures that made them some of the most visually arresting software you could run on an Apple II. And so Pierce worked furiously to crank the pictures out; John Williams remembers the poor kid “almost in tears” from the stress, but still frantically sketching away.

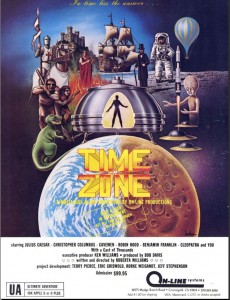

Even with such heroic efforts, there was no way Time Zone was going to be ready for Christmas. The project slipped into 1982, finally shipping (with a big sigh of relief from all concerned) about the beginning of March. Taking into account the sheer quantity of locations, On-Line decided the game was worth a premium price: in fact, a rather staggering list price of $99.95, about twice what anyone had dared to charge for even the most ambitious of computer games before. (Indeed, when accounting for inflation Time Zone is still quite possibly the most expensive videogame ever released.) For an advertisement, they created a mock movie poster, making the most explicit link yet between games and movies. It’s an interesting moment in this fraught relationship, a step on the way to the “interactive movies” On-Line and others would be touting a decade down the road.

Roberta also compared Time Zone to an “epic movie in the tradition of Cecil B. DeMille” in her CGW interview.

The introduction to the manual touts the size and scope of the project proudly, reminding one of the similar introduction to Wizardry‘s manual: “Time Zone has been over a year in the making”; “Roberta Williams spent over six months writing and designing the game before the first line of code for the game was actually written”; “it was the biggest project that On-Line Systems has ever embarked upon”; “it required a complete restructuring of our adventure programming procedures”; “Time Zone is by far the largest and most complex game ever written for any microcomputer.” An article in Softline stated, “This game took more than fourteen months to complete and it has been estimated that it will take people a year to solve due to its extreme complexity.” Predictably enough, an adventure fanatic named Roe Adams III finished it in just about a week, and promptly called On-Line to tell them about it. (I suspect Adams must have hacked — not because the amount of actual content in Time Zone really amounts to all that much but because of its handful of completely absurd puzzles. But I suppose a sufficiently methodical and patient man who went without sleep theoretically could solve the game in a week…)

None of the promotion helped very much. Time Zone became a notorious, high-profile flop, the first such that On-Line had ever released — and a fate it richly deserved. As John Williams wrote to me to open our discussion about the game, “It frankly wasn’t that good.” Indeed, Time Zone is something of a nadir in the annals of adventure-game design, the logical culmination of several ugly trends that I’ve been harping on about for quite some time now in this blog. It plays like a caricature of an old-school text adventure, with all of the annoyances of the form and too few of the delights, and with its rushed development peeking through from every crack and seam. More on that next time.

(Thanks for much in this post goes again to John Williams, whose memories are always invaluable to me.)