There’s a phenomenon we music fans often talk about called the “sophomore slump.” Before signing a record deal and recording that first album, bands generally spend years honing their craft and forging their musical identity. When they go into the studio for the first time at last, they know exactly who they are and what brought them here, and they also have the cream of all those years of songwriting at their disposal — polished, practiced, and audience tested. Yet when it comes time for the second album, assuming they get to make one, things are suddenly much more uncertain. All of those great songs that defined them were used up last time around, and now they’re left to pick through the material that didn’t make the cut and/or craft new stuff under time pressure they’ve never known before. Further, a sort of existential crisis often greets them. What kind of band do they want to be? Should they continue to work within the sound that got them this far, or should they push for more and get more experimental? Many try to split the difference, resulting in an uneven album unwilling to definitively do either, and full of songs and performances that, while perhaps perfectly competent, lack a certain pop, a spark of freshness compared to what came before.

I see some of the same thing in Zork II: The Wizard of Frobozz. Lebling and Infocom took some real, significant steps forward here, beginning to move beyond the “collect treasures for points” structure of the first game, but the whole thing feels a bit tentative. Infocom’s parser and world-modeling remain streets beyond what anyone else was doing, but they no longer carry quite the same shock of discovery. The writing gets sharper, funnier, and more consistent in tone, but, at least in the first release we’ll be looking at, the game suffers a bit from the need to have it out before Christmas, with an unusual (for Infocom) number of little bugs, glitches, and parser frustrations. There are some wonderful puzzles here along with some puzzles that just need an extra in-game nudge to be wonderful — in fact, far more of both than in Zork I — but also some absurd howlers, including the two most universally loathed in the entire Infocom canon. They’re proof that, while Lebling felt he should make Zork II harder than its predecessor, he wasn’t yet quite clear on the best way to accomplish that. So, like so many second albums, Zork II is a mixed bag. You can see it in very different ways depending on what you choose to emphasize, and, indeed, you’ll find very diverse opinions about its overall merit.

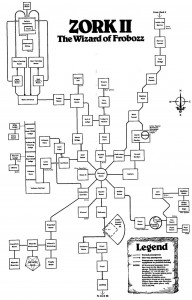

As I did with Zork I, I’m going to take you on a little tour of Zork II. The map above may help you to follow along. I’m also again making available the somewhat rare original story file for those seeking the most authentic historical experience. You can play it right in your browser, or download it to play in an interpreter that supports the Version 2 Z-Machine. Or you can choose the Apple II disk image.

We begin Zork II just where we presumably left off, inside the barrow which collecting the last of the treasures in Zork I opened up to us. Unlike in the PDP-10 Zork, the barrow has sealed behind us upon entrance, an obvious concession to the need to keep Zork I‘s chocolate separate from Zork II‘s peanut butter. We do have our two most faithful companions from Zork I, our lantern and our sword. (The lantern is also, thankfully, fully charged again for some unexplained reason.)

As soon as we begin to move deeper into the game from our initial location at the extreme north of the map, we see one of the more obvious and welcome signs of progress over its predecessor: Lebling now has no interest at all in making the geography itself into a puzzle. Everything connects with everything else in a consistent, straightforward manner, a far cry from the beginning of Zork I, where we were first challenged to spend an hour or two laboriously mapping all of the twisty intersections of the forest. Zork II doesn’t even feature the heretofore obligatory maze, at least in the conventional sense. (What replaces it is annoying enough that one is left wishing for a good old straightforward maze, but more on that later…)

Soon we have our first encounter with the man who will be our nemesis throughout the game: the Wizard of Frobozz.

A STRANGE LITTLE MAN IN A LONG CLOAK

APPEARS SUDDENLY IN THE ROOM. HE IS

WEARING A HIGH POINTED HAT EMBROIDERED

WITH ASTROLOGICAL SIGNS. HE HAS A LONG,

STRINGY, AND UNKEMPT BEARD.

THE WIZARD DRAWS FORTH HIS WAND AND

WAVES IT IN YOUR DIRECTION. IT BEGINS TO

GLOW WITH A FAINT BLUE GLOW.

THE WIZARD, IN A DEEP AND RESONANT

VOICE, SPEAKS THE WORD "FERMENT!" HE

CACKLES GLEEFULLY.

YOU BEGIN TO FEEL LIGHTHEADED.

The Wizard is one of Lebling’s innovations for the PC Zork II, and interesting on several levels. He appears more frequently and is characterized much more strongly than Zork I‘s thief. While the thief was a mere impediment and annoyance, our central goal in Zork II is to overcome the Wizard; thus his pride of place in the game’s subtitle. But never fear — the Wizard is also every bit as annoying as the thief ever was. He pops up from time to time to cast a randomly chosen spell on us, all of which begin with “F”: Filch, Freeze, Float, Fall, Fence, Fantasize, etc. Some of these, like Ferment, which makes us unable to walk straight for a (randomly chosen) number of turns, are mere inconveniences. Others — like Filch, which causes a randomly chosen item to disappear from our inventory, or Fall, which can kill us instantly if cast on, say, a cliff-side — leave us no recourse but to restore from our last save. What with our expiring, non-renewable light source, even the less potent spells become a problem in forcing us to waste precious turns waiting for their effects to expire. We pretty quickly get into the habit of just restoring every time we get spelled.

Every player will have to decide for herself whether the Wizard is funny enough to outweigh this annoyance factor. But the bumbling old Wizard, whose spells occasionally misfire in amusing ways, is genuinely funny.

THE WIZARD DRAWS FORTH HIS WAND AND

WAVES IT IN YOUR DIRECTION. IT BEGINS TO

GLOW WITH A FAINT BLUE GLOW.

THERE IS A LOUD CRACKLING NOISE. BLUE

SMOKE RISES FROM OUT OF THE WIZARD'S

SLEEVE. HE SIGHS AND DISAPPEARS.

Zork has always had a split personality. Authors give us either unabashedly silly, mildly satirical comedy, or an aged, now deserted world possessed of a lonely, faded grandeur. As the product of multiple authors writing pretty much to suit whatever whims struck them, Zork I itself pioneered both approaches, vacillating between them with no apparent concern. For every majestic Aragain Falls view, there was a cyclops to be fed hot peppers. With Zork II, however, Lebling has clearly decided to craft a “funny Zork.” And so we get various shoddy contraptions labeled as products of “The Frobozz Magic <insert item here> Company,” sort of the Wizard’s equivalent of Wile E. Coyote’s Acme Corporation. And we get lots of silly anecdotes about the excesses of the royal Flathead family and its patriarch, Lord Dimwit himself. Lebling shows a real gift for light comedy throughout, knowing how to craft jokes without trying too hard and beating us over the (flat)head with them.

In a gazebo in the garden, one of Lebling’s new additions, he places an homage to the original Zork, a copy of U.S. News and Dungeon Report.

** U.S. NEWS AND DUNGEON REPORT **

FAMED ADVENTURER TO EXPLORE GREAT

UNDERGROUND EMPIRE

OUR CORRESPONDENTS REPORT THAT A

WORLD-FAMOUS AND BATTLE-HARDENED

ADVENTURER HAS BEEN SEEN IN THE VICINITY

OF THE GREAT UNDERGROUND EMPIRE. LOCAL

GRUES HAVE BEEN REPORTED SHARPENING

THEIR (SLAVERING) FANGS....

"ZORK: THE WIZARD OF FROBOZZ" WAS

WRITTEN BY DAVE LEBLING AND MARC BLANK,

AND IS (C) COPYRIGHT 1981 BY INFOCOM,

INC.

You may remember that a magazine of the same title used to always sit inside the white house of the PDP-10 Zork to announce the latest news and additions to the online community that sprung up around the game.

Like its predecessors, Zork II imposes a pretty harsh inventory limit, forcing us to choose a base of operations to keep all of the stuff we collect. A good choice is the Carousel Room, a central hub around which the game’s geography — literally — revolves. (The game always chooses a random direction for us when we leave the Carousel Room; we can solve a puzzle to stop its rotation.) Indeed, there’s a definite combinatorial explosion that adds greatly to the difficulty. The map is a large one, and largely open from the start, leaving us to pick through piles of unsolved puzzles looking for the ones which we can actually solve at any given point. Just figuring out what we should be working on is much of the challenge.

Southeast of the Carousel Room is the appropriately named Riddle Room. In front of a sealed door we read the following:

WHAT IS TALL AS A HOUSE,

ROUND AS A CUP,

AND ALL THE KING'S HORSES

CAN'T DRAW IT UP?

The answer is a well.

Riddles aren’t really approved practice in interactive-fiction design these days, largely because they’re just so dependent on intuition and all too often very culturally specific, and thus notoriously variable in difficulty from player to player. There’s also a certain element of cheapness about them, a quality they share with mazes. A designer in need of a puzzle can throw in a riddle in a matter of minutes, then watch contentedly as at least some subset of her players agonize for hours. Still, as adventure-game riddles go this one isn’t awful, and there is an undeniable thrill in getting a riddle in a flash of insight — much like when solving other, better respected sorts of adventure-game puzzles. In Twisty Little Passages, Nick Montfort names the riddle as the text adventure’s most important literary antecedent. I’m not entirely convinced of that, but if true it does present the opportunity to view Zork‘s riddle as this new form already glancing back to its roots. Not that I believe for a moment that anything of the sort was on the designers’ minds.

Beyond the Riddle Room is the Circular Room:

CIRCULAR ROOM

THIS IS A DAMP CIRCULAR ROOM, WHOSE

WALLS ARE MADE OF BRICK AND MORTAR. THE

ROOF OF THIS ROOM IS NOT VISIBLE, BUT

THERE APPEAR TO BE SOME ETCHINGS ON THE

WALLS. THERE IS A PASSAGEWAY TO THE

WEST.

THERE IS A WOODEN BUCKET HERE, 3 FEET IN

DIAMETER AND 3 FEET HIGH.

With a little thought, not to mention some consideration of the riddle we just solved, we can conclude that we are standing at the bottom of a well. It turns out that it’s not just a well, but a magic well; if we pour some water into the bucket, it will hoist us up to a new area at its top. I mentioned earlier that a number of puzzles in Zork II are just a nudge away from being excellent. This one is a good example. While there’s a certain elegant logic to it, we aren’t told that it’s a magic well until we reach the top and see the “Frobozz Magic Well Company” logo. It’s just a little bit too much of a stretch in its present form. Or maybe I’m supposed to be able to find some clue in these etchings found at the bottom:

O B O

A G I

E L

M P A

If anyone can figure out what that’s on about, let me know.

At the top of the well is the so-called “Alice” area. Lewis Carroll would prove to be a great favorite of adventure-game writers because his blend of surrealism, logical illogic, and love of puzzles fit the genre so well, making his works just about as perfect as any traditional literature can be for adaptation to the adventure-game form. Before any official adaptations, however, Infocom paid him homage here. (Like the well area, the Alice area was present in the PDP-10 version, and thus dates to approximately 1978.) We find some cakes with the expected effect on our size, and once appropriately shrunken visit a pool of tears lifted straight from Chapter 2 of Alice in Wonderland. It all makes for some lovely puzzles. It’s sort of amusing that we must travel up a well to visit the Alice area in Zork II, while Alice fell down a well to start her adventures in the book. Of course, there’s also quite a similarity between the premise of the Zork games as a whole and that of the Alice books. Both include vast magical landscapes accessed via the most mundane of gateways, and both are all about puzzles and play rather than plot.

As already demonstrated via the Wizard, Zork II does have a modicum more interpersonal interaction than its predecessor, making adventuring in these dungeons feel just a bit less lonely. For the first time (discounting the PDP-10 version) it allows us to actually talk to other characters, entering into some fraught territory that still bedevils IF authors today. Zork II‘s system is still pretty awkward: we can only “TELL <someone> ‘<something>’,” with the quotes a necessity. It does, however, allow for a pretty impressive demonstration of Infocom’s technology, in the form of a little robot also located at the top of the well whom we can order about just as if he were, well, us. (Like Zork I, Zork II happily jumps from science-fiction robots to fantasy monsters to present-day elements with no compunction whatsoever.) The robot is key to another of those puzzles that just needed a little bit more work to be great.

There’s a magical sphere that we’d really like to loot, but it’s protected by the “Frobozz Magic Alarm Company.” When we try to take it, a cage drops around us, the room fills with a poison gas, and we die after a couple of turns. Trying to get the robot to take the sphere for us doesn’t work. The cage crushes the poor little guy rather than merely trapping him for some reason, in a scene oddly reminiscent of a famous incident from Infocom’s later Planetfall. The sphere, meanwhile, disappears (presumably it’s inside the cage). The solution is to have the robot in the room with us when we trigger the trap, then have him “GET CAGE” to get us free before the gas asphyxiates us. In the abstract it’s not a bad puzzle. However, it’s so fraught with implementation problems that it’s well-nigh impossible to deduce what’s really going on. The game gives us no sign that we can still interact with the robot at all from inside the cage. Even if we make that cognitive leap on our own, it still refuses to make anything easy for us.

>GET SPHERE

AS YOU REACH FOR THE SPHERE, A STEEL

CAGE FALLS FROM THE CEILING TO ENTRAP

YOU. TO MAKE MATTERS WORSE, POISONOUS

GAS STARTS COMING INTO THE ROOM.

CAGE

YOU ARE TRAPPED INSIDE A STEEL CAGE.

>TELL ROBOT "GET GAS"

I DON'T KNOW THE WORD 'GAS'.

>TELL ROBOT "HELP"

I DON'T KNOW THE WORD 'HELP'.

>TELL ROBOT "N"

"WHIRR, BUZZ, CLICK!"

YOU CAN'T GO THAT WAY.

>L

CAGE

YOU ARE TRAPPED INSIDE A STEEL CAGE.

>EXAMINE CAGE

I SEE NOTHING SPECIAL ABOUT THE STEEL

CAGE.

>TELL ROBOT "BREAK CAGE"

WHAT DO YOU WANT TO BREAK THE CAGE WITH?

>ROBOT

TRYING TO DESTROY THE STEEL CAGE HAS NO

EFFECT.

>TELL ROBOT "GET CAGE"

THE CAGE SHAKES AND IS HURLED ACROSS THE

ROOM. IT'S HARD TO SAY, BUT THE ROBOT

APPEARS TO BE SMILING.

DINGY CLOSET

THERE IS A BEAUTIFUL RED CRYSTAL SPHERE

HERE.

>GET SPHERE

TAKEN.

I’ve edited out from the above the dying every couple of turns.

Questions abound. Where actually was the sphere when we were inside the cage, since it was apparently neither inside nor outside? Why does “GETting” the cage cause the robot to break it, and “BREAKing” it get us nowhere? It’s issues like this that sometimes make Zork II, at least in this first released version, feel a bit undercooked.