One night circa early 1981, Silas Warner of Muse Software dropped by a local 7-Eleven store, where he saw an arcade game called Berzerk.

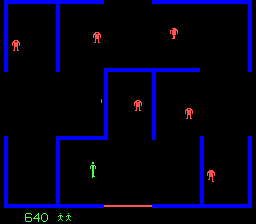

Berzerk essentially played like an interactive version of the programming game Warner had just finished writing on the Apple II, Robot War. The player controlled a “humanoid” who looked more than a little like a robot himself, battling an array of other robots each equipped with their own armaments and personalities. But most impressively, Berzerk talked. The enemy robots shouted out science-fiction cliches like “Intruder alert!” and, Dalek style, single-word imperatives like “Attack!,” “Kill!,” and “Destroy!” Warner was entranced, especially considering that one of Muse’s flagship products was Warner’s own The Voice, an Apple II voice-synthesis system. Still, he’d had enough of robots for a while.

Then one night the old World War II flick The Guns of Navarone came on the television. The most successful film of 1961, it’s the story of a tiny group of Allied commandos who make their way across a (fictional) Greek island to destroy a vital German gun installation. Like most films of its ilk, it can be good escapist fun if you’re in the right frame of mind, even if most of its plot is forehead-slappingly silly. After seeing Navarone, Warner started thinking about whether it might be possible to replace robots with Nazis. One nice thing about filmic Nazis, after all, is that they tend to be as aggressively stupid as videogame robots, marching blithely into trap after ambush after deception while periodically shouting out “Achtung!,” “Jawohl!,” and “Sieg Heil!” in lieu of Berzerk‘s “Attack!,” “Kill!,” and “Destroy!” (One imagines that the Greeks in the movie, when not engaging in ethnically appropriate song and dance or seducing our heroes with their dewy-eyed, heroic-resistance-fighter gazes, must be wondering just how the hell they managed to get themselves conquered by this bunch of clowns.) Other elements of the movie also held potential. The heroes spend much of the latter half disguised in German uniforms, sneaking about until someone figures out the ruse and the killing has to start again. What a game mechanic!

So, from the odd couple of Berzerk and The Guns of Navarone was born Castle Wolfenstein.

Given Wolfenstein‘s position in the history of ludic narrative, it’s appropriate that it should have resulted from the pairing of an arcade game with a work of fiction. Wolfenstein was the first game to unify the two strands of computer gaming I described in my previous post, combining a real story and fictional context with action mechanics best carried out with a joystick or set of paddles. Yet even this gameplay also demanded considerable thought, even strategizing, for success. In the console world, Warren Robinett had attempted a similar fusion a couple of years earlier with the Atari VCS game Adventure, which was directly inspired by Crowther and Woods’s game of the same name. Still, the VCS was horribly suited to the endeavor. Because it couldn’t display text at all, Adventure couldn’t set the scene like Wolfenstein did when the player first started a game. The following is mouthed by a dying cellmate in the castle/fortress in which you are being held prisoner:

“WELCOME TO CASTLE WOLFENSTEIN, MATE! THE NAZIS BROUGHT YOU HERE TO GET INFORMATION OUT OF YOU BEFORE THEY KILL YOU. THAT’S WHAT THIS PLACE IS FOR – IF YOU LISTEN YOU CAN HEAR THE SCREAMS. THEY’VE ALREADY WORKED ME OVER AND I’LL NEVER GET OUT ALIVE, BUT MAYBE YOU CAN WITH THIS GUN. I GOT IT OFF A DEAD GUARD BEFORE THEY CAUGHT ME. IT’S STANDARD ISSUE – EACH CLIP HOLDS 10 BULLETS, AND IT’S FULLY LOADED.

“BE CAREFUL, MATE, BECAUSE EVERY ROOM IN THE CASTLE IS GUARDED. THE REGULAR GUARDS CAN’T LEAVE THEIR POSTS WITHOUT ORDERS, BUT WATCH OUT FOR THE SS STORMTROOPERS. THEY’RE THE ONES IN THE BULLETPROOF VESTS AND THEY’RE LIKE BLOODY HOUNDS. ONCE THEY’VE PICKED UP YOUR TRAIL THEY WON’T STOP CHASING YOU UNTIL YOU KILL THEM AND YOU ALMOST NEED A GRENADE TO DO THAT.

“CASTLE WOLFENSTEIN IS FULL OF SUPPLIES TOO. I KNOW ONE CHAP WHO FOUND A WHOLE GERMAN UNIFORM AND ALMOST SNEAKED OUT PAST THE GUARDS. HE MIGHT HAVE MADE IT IF HE HADN’T SHOT SOME POOR SOD AND GOT THE SS ON HIS TRAIL. IF YOU CAN’T UNLOCK A SUPPLY CHEST, TRY SHOOTING IT OPEN. NOW I WOULDN’T GO SHOOTING AT CHESTS FULL OF EXPLOSIVES…

“ONE MORE THING. THE BATTLE PLANS FOR OPERATION RHEINGOLD ARE HIDDEN SOMEWHERE IN THE CASTLE. I’M SURE YOU KNOW WHAT IT WOULD MEAN TO THE ALLIED HIGH COMMAND IF WE COULD GET OUR HANDS ON THOSE…

“THEY’RE COMING FOR ME! GOOD LUCK!

“AIIIIEEEEEEE….”

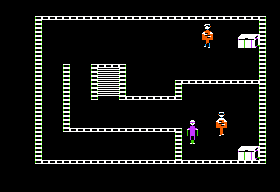

Once into the game proper the text dries up, but there are still elements that make it feel like some facsimile of a real situation rather than an exercise in abstract arcade mechanics. The “verbs” available to the player are very limited in comparison to, say, even an old-school text adventure: move, aim, shoot, search a surrendered soldier or corpse, open a door or chest, throw a grenade, use a special item, take inventory. Yet the game’s commitment to simulation is such that this limited suite of actions yields a surprising impression of verisimilitude. One can, for example, use a grenade to blow up guards, but one can also use it to blast holes in walls. Such possibilities make the game a tour de force of early virtual worldbuilding; arguably no one had created a simulated world so believable on such a granular level prior to Wolfenstein.

There is even some scope for moral choice. If you catch them by surprise, guards will sometimes lift their arms in surrender, at which point you are free to kill them or leave them alive, as you will. Similarly, the game allows different approaches to its central problem of escape. One can attempt to methodically dispatch every single guard in every single room, but one can also try to dodge past them or outrun them, only killing as a last resort. Or one can find a uniform, and (in the game’s most obvious homage to The Guns of Navarone) try to just walk right out the front door that way. These qualities have led many to call Wolfenstein the first ancestor of the much later genre of stealth-based games like Metal Gear Solid and Thief. I don’t know as much about such games as I probably ought to, but I see no reason to disagree. The one limiting factor on the “sneaking” strategy is the need to find those battle plans in order to achieve full marks. To do that you have to search the various chests you come across, something which arouses the guards’ suspicion. (These may be videogame Nazis, but they aren’t, alas, quite that stupid.)

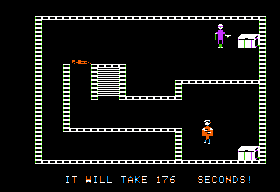

In order to make the game a replayable exercise (shades of the arcade again), the castle is randomly stocked with guards and supplies each time the player begins a new game. In addition, play progresses through a series of levels. The first time you play you are a private, and things are appropriately easier — although, it should be noted, never easy; Wolfenstein is, at least for me, a punishingly difficult game. Each time you beat the game on a given level, you increase in rank by one, and everything gets more difficult the next time around. The ultimate achievement is to become a field marshal.

In Warner’s own words, he threw “everything” Muse had on their shelf of technical goodies into Wolfenstein. For instance, we once more see here the high-res character generator Warner had also used in Robot War.

But most impressive was the inclusion of actual speech, a first for a computer game. To really appreciate how remarkable this was, you first have to understand how extraordinarily primitive the Apple II’s sound hardware actually was. The machine contained no sound synthesizer or waveform generator. A program could make sound only by directly toggling current to the speaker itself. Each time it did this, the result was an audible click. Click the speaker at the appropriate frequency, and you could create various beeps and boops, but nothing approaching the subtlety of human speech — or so went the conventional wisdom. The story of Wolfenstein‘s talking Nazis begins back in 1978, when a programmer named Bob Bishop released a pair of programs called Apple-Lis’ner and Appletalker.

Every Apple II shipped with a port that allowed a user to connect to it a standard cassette drive for storage, as well as the internal hardware to convert binary data into sound for recording and vice versa. Indeed, cassettes were the most common storage medium for the first few years of the Apple II’s life. Bishop realized that, thanks to the cassette port, every Apple II effectively contained a built-in audio digitizer, a way of converting sound data into binary data. If he attached a microphone to the cassette port, he should be able to “record” his own speech and store it on the computer. He devised a simplistic 1-bit sampling algorithm: for every sample at which the level of the incoming sound was above a certain threshold, click the speaker once. The result, as played back through Appletalker, was highly distorted but often intelligible speech. Warner refined Bishop’s innovations in 1980 in The Voice. It shipped with a library of pre-sampled phonemes, allowing the user to simply enter text at the keyboard and have the computer speak it — if the program properly deduced what phoneme belonged where, of course.

For Wolfenstein, Warner took advantage of an association that Muse had with a local recording studio, who processed Muse’s cassette software using equalizers and the like to create tapes that Muse claimed were more robust and reliable than those of the competition. Warner: “We went down there [to the studio] one fine day, and I spent several hours on the microphone saying, ‘Achtung!'” Given the primitive technology used to create them (not to mention Warner’s, um, unusual German diction), Wolfenstein‘s assorted shouts were often all but indecipherable. Rather than hurting, however, the distortion somehow added to the nightmare quality of the scenario as a whole, increasing the tension rather than the contrary.

Warner’s magnum opus as a designer and programmer, Castle Wolfenstein remained Muse’s most successful product and reliable seller from its release in September of 1981 through Muse’s eventual dissolution, not only in its original Apple II incarnation but also in ports to the Atari 400 and 800, MS-DOS, and (most notably) the Commodore 64. Muse produced a belated sequel in 1984, Beyond Castle Wolfenstein, in which the player must break into Adolf Hitler’s underground bunker to assassinate the Fūhrer himself rather than break out of a generic Nazi fortress. However, while Warner was involved in design discussion for that game, the actual implementation was done by others. The following year, Muse suddenly collapsed, done in by a string of avoidable mistakes in a scenario all too common for the early, hacker-led software publishers. Warner stayed in the games industry for another decade after Muse, but never found quite the creative freedom and that certain spark of something that had led to Robot War and Castle Wolfenstein in his banner year of 1981. He died at the age of 54 in 2004. Wolfenstein itself, of course, lived on when id Software released Wolfenstein 3D, the precursor to the landmark Doom, in 1992.

Whether we choose to call Castle Wolfenstein the first PC action adventure or the first stealth game or something else, its biggest importance for ludic narrative is its injection of narrative elements into a gameplay framework completely divorced from the text adventures and CRPGs that had previously represented the category on computers. As such it stands at the point of origin of a trend that would over years and decades snowball to enormous — some would say ridiculous — proportions. Today stories in games are absolutely everywhere, from big-budget FPSs to casual puzzlers. With its violence and cartoon-like Nazi villains, Wolfenstein is perhaps also a harbinger of how cheap and coarse so many of those stories would be. But then again, we can’t really blame Warner for that, can we?

If you’d like to try Silas Warner’s greatest legacy for yourself, you can download the Apple II disk image and manual from here.

Next time we have some odds and ends to clean up as we begin to wrap up 1981 at last.