Before the famous Videogame Crash of 1983 there was the Videogame Crash of 1976. By that year Atari’s Pong had been in arcades for four years, along with countless ball-bouncing variants: Handball, Hockey, Pin Pong, Dr. Pong, and of course Breakout. The public was already growing bored of all of them, as well as with the equally simplistic driving and shooting games that made up the rest of arcade fare. As videogame revenues declined, pinball, the form they were supposed to have superseded, started to make a comeback. Even Atari themselves started a pinball division, as manufacturers began applying some of the techniques they’d learned in videogames to a new generation of electromechanical pinball tables that rewarded players with lots of sounds, flashing lights, and high-score leaderboards. When Atari introduced its VCS home-game console in October of 1977, sales were predictably sluggish. Then, exactly one year later, Space Invaders arrived.

Developed by the Japanese company Taito and manufactured and sold in North America under license by Midway, Space Invaders had the perfect theme for a generation of kids entranced with Star Wars and Close Encounters. Its constant, frenetic action and, yes, the violence of its scenario also made it stand out markedly from comparatively placid games like Pong and Breakout. Space Invaders became the exemplar of videogames in general, the first game the general public thought of when one mentioned the form. With coin-operated arcade games suddenly experiencing a dramatic revival, sales of the Atari VCS also began to steadily increase. Thanks to a very good holiday season, sales for 1979 hit 1 million.

However, the real tipping point that would eventually result in Atari VCSs in more than 15% of U.S. homes came when Manny Gerard and Ray Kassar, Atari’s vice president and president respectively, negotiated a deal with their ostensible rivals Taito and Midway to make a version of Space Invaders for the VCS. Kassar is known today as the man who stifled innovation at Atari and mistreated his programmers so badly that the best of them decided to form their own company, Activision. Still, his marketing instinct at this moment was perfect. Kassar predicted that Space Invaders would not only be a huge hit with the VCS’s existing owners, but that it would actually sell consoles to people who wanted to play their arcade favorite at home. He was proven exactly right upon the VCS Space Invaders‘s release in January of 1980. The VCS, dragged along in the wake of the game, doubled its sales in 1980, to 2 million units.

Atari took the lesson of Space Invaders to heart. Instead of investing energy into original games with innocuously descriptive titles like Basketball, Combat, and Air Sea Battle, as they had done for the first few years of the VCS, they now concentrated on licensing all of the big arcade hits. Atari had learned an important lesson: that the quantity and quality of available software is more important to a platform than the technical specifications of the platform itself. This fact would allow the Atari VCS to dominate the console field for years despite being absurdly primitive in comparison to competition like the Intellivision and the Vectrex.

Apple was learning a similar lesson at this time in the wake of the fortuitous decision that Dan Bricklin and Bob Frankston made to first implement VisiCalc on the Apple II. Indeed, one could argue that the survivors from the early PC industry — companies like Apple and, most notably, Microsoft — were the ones that got the supreme importance of software, while those who didn’t — companies like Commodore, Radio Shack’s computer division, and eventually Atari itself — were the ones ultimately destined for the proverbial dustbin of history. Software like VisiCalc provided an answer to the question that had been tripping up computer hobbyists for years when issued from the mouths of wives, girlfriends, and parents: “But what can you really do with it?” A computer that didn’t have a good base of software, no matter how impressive its hardware, wasn’t much use to the vast majority of the public who weren’t interested in writing their own programs.

With all this in mind, let’s talk about computer games (as opposed to console games) again. We can divide entertainment software in these early years into two broad categories, only one of which I’ve so far concerned myself with in this blog. I’ve been writing about the cerebral branch of computer gaming, slow-paced works inspired by the tabletop-gaming and fiction traditions. These are the purest of computer games, in that they existed only on PCs and, indeed, would have been impossible on the game consoles of their day. They depend on a relatively large memory to hold their relatively sophisticated world models (and, increasingly, disk storage to increase the scope of possibility thanks to virtual memory); a keyboard to provide a wide range of input possibilities; and the ability to display text easily on the screen to communicate in relatively nuanced ways with their players.

The other category consists of arcade-style gameplay brought onto the PC. With the exception of the Atari 400 and 800, none of the earliest PCs were terribly suited to this style of game, lacking sprites and other fast-animation technologies and often even appropriate game controllers. Yet with the arcade craze in full bloom, these games became very, very popular. Even the Commodore PET, which lacked any bitmapped graphics mode at all, had a version of Breakout implemented entirely in “text” using the machine’s extended ASCII character set.

On a machine like the Apple II, which did have bitmapped graphics, such games were even more popular. Nasir Gebelli and Bill Budge were the kings of the Apple II action game, and as such were known by virtually every Apple II hobbyist. Even Richard Garriott, programmer of a very different sort of game, was so excited upon receiving that first call from California Pacific about Akalabeth because CP was, as everyone knew, the home of Budge. If Computer Gaming World is to be believed, it was not Zork or Temple of Apshai or Wizardry that was the bestselling Apple II game of all time in mid-1982, but rather K-Razy Shootout, a clone of the arcade game Berzerk. They may have sold in minuscule numbers compared to their console counterparts and may not have always looked or played quite as nicely, but arcade-style games were a big deal on PCs right from the start. When the Commodore VIC-20 arrived, perched as it was in some tenuous place between PC and game console, the trend only accelerated.

You may have noticed a theme in my discussion of these games in this post and in a previous post: many of these games were, um, heavily inspired by popular coin-operated arcade games. In the earliest days, when the PC-software industry was truly minuscule and copyright still a foreign concept to many programmers, many aspired to make unabashed clones of the latest arcade hits, down to the name itself. By 1980, however, this approach was being replaced by something at least a little more subtle, in which programmers duplicated the gameplay but changed the title and (sometimes, to some extent) the presentation. It should be noted that not all PC action-game programmers were cloners; Gebelli and Budge, for instance, generally wrote original games, and perhaps therein lies much of their reputation. Still, clones were more the rule than the exception, and by 1981 the PC software industry had grown enough for Atari to start to notice — and to get pissed off about it. They took out full-page advertisements in many of the big computer magazines announcing “PIRACY: THIS GAME IS OVER.”

Some companies and individuals have copied Atari games in an attempt to reap undeserved profits from games that they did not develop. Atari must protect its investment so that we can continue to invest in new and better games. According, Atari gives warning to both the intentional pirate and to the individuals simply unaware of the copyright laws that Atari registers the audiovisual works associated with its games with the Library of Congress and considers its game proprietary. Atari will protect its rights by vigorously enforcing these copyrights and by taking the appropriate action against unauthorized entities who reproduce or adapt substantial copies of Atari games, regardless of what computer or other apparatus is used in their performance.

In referring to cloning as “piracy,” Atari is conflating two very separate issues, but they aren’t doing so thoughtlessly — there’s a legal strategy at work here.

Literally from the dawn of the PC era, when Bill Gates wrote his famous “Open Letter to Hobbyists,” software piracy was recognized by many in the industry as a major problem, a problem that some even claimed could kill the whole industry before it got properly started. Gates considered his letter necessary because the very concept of commercial software was a new thing, as new as the microcomputer itself. Previously, programs had been included with hardware and support contracts taken out with companies like IBM and DEC, or traded about freely amongst students, hackers, and scientists on the big machines. In fact, it wasn’t at all clear that software even could be copyrighted. The 1909 Copyright Act that was still in effect when Gates wrote his letter in January of 1976 states that to be copyrightable a work must be “fixed in a tangible medium of expression.” One interpretation of this requirement holds that an executable computer program, since it lives only electronically within the computer’s memory, fails the tangibility test. The Copyright Act of 1976, a major amendment, failed to really clarify the situation. Astonishingly, it was only with the Computer Software Copyright Act of 1980 that it was made unambiguously clear that software was copyrightable in the same way as books and movies and that, yes, all those pirates were actually doing something illegal as well as immoral.

But there was still some confusion about exactly what aspect of a computer program was copyrightable. When we’re talking about copyright on a book, we’re obviously concerned with the printed words on the page. When we’re talking about copyright on a film, we’re concerned with the images that the viewer sees unspooling on the screen and the sounds that accompany them. A computer program, however, has both of these aspects. There’s the “literary” side, the code to be run by the computer, which in many cases takes two forms, the source code written by the programmer and the binary code that the computer actually executes after the source has been fed through an assembler or compiler. And then there’s the “filmic” side, the images that the viewer sees on the screen before her and the sounds she hears. The 1980 law defines a computer program as a “set of statements or instructions to be used directly or indirectly in a computer in order to bring about a certain result.” Thus, it would seem to extend protection to source and executable code, but not to the end experience of the user.

Such protection was not quite enough for Atari. They therefore turned to a court case of 1980, Midway vs. Dirkschneider. Dirkschneider was a small company who essentially did in hardware what many PC programmers were doing in software, stamping out unauthorized clones of games from the big boys like Atari and Midway, then selling them to arcade operators at a substantial discount on the genuine article. When they started making their own version of Galaxian, one of Midway’s most popular games, under the name Galactic Invader, Midway sued them in a Nebraska court. The judge in that case ruled in favor of the plaintiff, on the basis of a new concept that quickly became known as the “ten-foot rule”: “If a reasonable person could not, at ten feet, tell the difference between two competitive products, then there was cause to believe an infringement was occurring.”

So, in conflating pirates who illegally copied and traded software with cloners who merely copied the ideas and appearance of others’ games, implementing them using entirely original code, Atari was attempting to dramatically expand the legal protections afforded to software. The advertisement is also, of course, a masterful piece of rhetoric meant to tar said cloners with the same brush of disrepute used for the pirates, who were criticized in countless hand-wringing editorials in the exact same magazines in which Atari’s advertisement appeared. All of this grandstanding moved out of the magazines and into the courts in late 1981, via the saga of Jawbreaker.

The big arcade hit of 1981 was Pac-Man. In fact, calling Pac-Man merely “big” is considerably underestimating the matter. The game was a full-fledged craze, dwarfing the popularity of even Space Invaders. Recent studies have shown Pac-Man to still be the most recognizable videogame character in the world, which by extension makes Pac-Man easily the most famous videogame ever created. Like Space Invaders, Pac-Man was an import from Japan, created there by Namco and distributed, again like Space Invaders, by Atari’s arch-rival of the standup-arcade world, Midway. Said rivalry did not, however, prevent the companies from working out a deal to get Pac-Man onto the Atari VCS. It was to be released just in time for Christmas 1981, and promised to be the huge VCS hit of the season. Kassar and his cronies rubbed their hands in anticipation, imagining the numbers it would sell — and the number of VCSs it would also move as those who had been resistant so far finally got on the bandwagon.

Yet long before the big release day came, John Harris, Ken Williams’s star Atari 400 and 800 programmer at On-Line Systems, had already written a virtually pixel-perfect clone of the game after obsessively studying it in action at the local arcade. Ken took one look and knew he didn’t dare release it. Even leaving aside Atari’s aggressive attempts to expand the definition of software “piracy,” the Pac-Man character himself was trademarked. Releasing the game as-is risked lawsuits from multiple quarters, all much larger and richer in lawyers than On-Line Systems. The result could very well be the destruction of everything he had built. Yet, the game was just so damn good. After discussing the problem with others, Ken told Harris to go home and redo the game’s graphics to preserve the gameplay but change the theme and appearance. Harris ended up delivering a bizarre tribute to the seemingly antithetical joys of candy and good dental hygiene. Pac-Man became a set of chomping teeth; the dots Life Savers; the ghosts jawbreakers. Every time the player finished a level, an animated toothbrush came out to brush her avatar’s teeth. None of it made a lot of sense, but then the original Pac-Man made if anything even less. Ken put it out there. It actually became On-Line’s second Pac-Man clone; another one called Gobbler was already available for the Apple II.

Meanwhile Atari, just as they had promised in that advertisement, started coming down hard on Pac-Man cloners. They “persuaded” Brøderbund Software to pull Snoggle for the Apple II off the market. They “convinced” a tiny publisher called Stoneware not to even release theirs, despite having already invested money in packaging and advertising. And they started calling Ken.

The situation between On-Line and Atari was more complicated than the others. Jawbreaker ran on Atari’s own 400 and 800 computers rather than the Apple II. On the one hand, this made Atari even more eager to stamp it out of existence, because they themselves had belatedly begun releasing many of their bestselling VCS titles (a group sure to include Pac-Man) in versions for the 400 and 800. On the other hand, though, this represented an opportunity. You see, Harris had naively given away some copies of his game back when it was still an unadulterated Pac-Man. Some of these (shades of Richard Garriott’s experience with California Pacific) had made it all the way to Atari’s headquarters. Thus their goals were twofold: to stamp out Jawbreaker, but also if possible to buy this superb version of Pac-Man to release under their own imprint. Unfortunately, Harris didn’t want to sell it to them. He loved the Atari computers, but he hated the company, famous by this time for their lack of respect for the programmers and engineers who actually built their products. (This lack of respect was such that the entire visionary team that had made the 400 and 800 had left the company by the time the machines made it into stores.)

At the center of all this was Ken, the very picture of a torn man. He wasn’t the sort who accepts being pushed around, and Atari were trying to do just that, threatening him with all kinds of legal hellfire. Yet he also knew that, well, they kind of had a point; if someone did to one of his games what On-Line was doing to Pac-Man, he’d be mad as hell. Whatever the remnants of the hippie lifestyle that hung around On-Line along with the occasional telltale whiff of marijuana smoke, Ken didn’t so much dream of overthrowing the man as joining him, of building On-Line into a publisher to rival Atari. He wasn’t sure he could get there by peddling knockoffs of other people’s designs, no matter how polished they were.

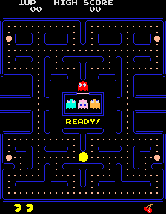

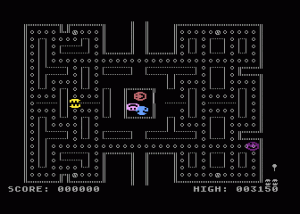

Thanks largely to Ken’s ambivalence, the final outcome of all this was, as tends to happen in real life, somewhat anticlimactic. On-Line defied Atari long enough to get dragged into court for a deposition, at which Atari tried to convince the judge to grant a preliminary injunction forcing On-Line to pull Jawbreaker off the market pending a full trial. The judge applied the legal precedent of the ten-foot rule, and, surprisingly, decided that Jawbreaker looked different enough from Pac-Man to refuse Atari’s motion. You can judge for yourself: below is a screenshot of the original arcade Pac-Man pair with one of Jawbreaker.

Atari’s lawyers were reportedly stunned at the rejection, but still, Ken had no real stomach for this fight. He walked out of the courtroom far from triumphant: “If this opens the door to other programmers ripping off my software, what happened here was a bad thing.” Shortly after, he called Atari to see if they couldn’t work something out to keep Jawbreaker on the market but share the wealth.

Right on schedule, Atari’s own infamously slapdash implementation of Pac-Man appeared just in time for Christmas. It moved well over 7 million units to consumers who didn’t seem to care a bit that the ghosts flickered horribly and the colors were all wrong. The following year, On-Line and Harris developed a version of the now authorized Jawbreaker for the Atari VCS, publishing it through a company called Tigervision. It didn’t sell a fraction of what its inferior predecessor had sold, of course, but it did represent a change in the mentality of Ken and his company. Much of the fun and craziness continued, but they were also becoming a “real” company ready to play with the big boys like Atari — with all the good and bad that entails.

Similar changes were coming to the industry as a whole. Thanks to Atari’s legal muscling, blatant clones of popular arcade games dried up. The industry was now big enough to attract attention from outside its own ranks, with the result that intellectual property was starting to become a big deal. Around this time Edu-Ware got sued for its Space games that were a little bit too inspired by Game Designers’ Workshop’s Traveller tabletop RPG; they replaced them with a new series in the same spirit called Empire. Scott Adams got threatened with a lawsuit of his own over Mission Impossible Adventure, and in response changed the name to Secret Mission.

Indeed, 1981 was the year when the microcomputer industry as a whole went fully and irrevocably professional, as punctuated by soaring sales of VisiCalc and the momentous if belated arrival of IBM on the scene. That’s another story we really have to talk about, but later. Next time, we’ll see how the two broad styles of computer gaming met one another in a single game for the first time.

(My most useful sources in writing this post were an article by Al Tommervik in the January 1982 Softline and Steven Levy’s Hackers.)