If you asked the average man on the street circa 1981, he’d probably be hard put to imagine two nouns so divorced from one another as sex and computer. Most people still saw computers as dully esoteric tools maintained by a priesthood of little gnomes seeking refuge from the real world of playground bullies, gym teachers, and, most terrifying of all, women. Stereotypes generally being stereotypes for a reason, that description may arguably apply to plenty of folks we’ve met on this blog before, at least if we insist on casting these characters in their most unfavorable possible light. But still, gnomes have needs too — as do hackers. One had only to look at the chainmail bikinis on the covers of fantasy novels, Dungeons and Dragons boxes, and, soon enough, computer games to know that nerds were far from asexual, even if many of them weren’t actually getting much of it. Rather than being separate universes, sex and computers were at worst adjacent galaxies, which orbited into contact with one another more often than our man on the street would ever suspect.

During the mid-1960s, Ken Knowlton was working with computer graphics at the legendary Bell Labs, home of such diverse achievements as the development of the C programming language and the Unix operating system and the detection of the background radiation from the Big Bang among a thousand others. He had developed a primitive video digitizer, the forerunner of the digital cameras of today, which could scan a photograph, sorting it into a grid of light and dark pixels. However, Knowlton did not have access to a proper bitmapped display, only text-oriented teletypes. He therefore developed software to convert the scanned pixels into individual letters chosen for their relative brightness and similarity to the patterns in the photograph. One day in 1966 when their boss was away on holiday, Knowlton and a colleague, Leon Harmon, conspired to scan in a nude photo of dancer Deborah Hay, blow it up to truly mammoth proportions, and plaster their (apparently very easygoing) boss’s wall with it.

The picture was quickly retired after the boss’s return, but nevertheless propagated electronically through the computer industry. Finally it came to attention of The New York Times, who printed it along with an article on the bizarre new idea of “computer art” in October of 1967. It was allegedly the first nude image of any stripe that the famously decorous Gray Lady had ever printed. On the basis of that exposure, this elaborate practical joke found its way into The Machine as Seen at the End of the Mechanical Age, a 1968-69 exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York that featured some of the first examples of computer art to appear in a gallery setting. For the show it was given the appropriately pretentious moniker Studies in Perception #1. Today it resides in the collection of the Victoria and Albert Museum in London. In demonstrating that ordinary letters could be, well, sexy, Knowlton and Harmon kickstarted the practice of ASCII art, a practice that still has devoted adherents today.

Knowlton tells a story typical of many artists and engineers working in new mediums:

We did make similar pictures — of a gargoyle, of seagulls, of people sitting at computers — which have appeared here and there. But it was our Nude who would dolphin again and again into public view in dozens of books and magazines.

The earliest artwork produced on microcomputers was ASCII art — the PET and TRS-80 in particular were capable of little else — and much of it likewise featured nudes. These tiny files, traded about over the ARPANET, on disks, and through the first computerized bulletin-board systems, represent some of the first digital pornographic images.

Anyone who studies the history of technology comes to understand quickly that just about any new technology that can conceivably be applied to sex will be in pretty short order. Many subjects of early photographers were featured sans clothing; many of the earliest movies were peepshows; many or most early VCRs were bought to watch porn movies at home without the discomfort and embarrassment of visiting a theater. And porn drove the early growth of the Internet to an extent few are comfortable acknowledging, dwarfing everything else in profitability during those heady early days of the mid-1990s. The microcomputer itself was no real exception to the rule, even if the mixing of computers and sex was initially awkward and, like all those ASCII images of naked women, of decidedly limited fidelity.

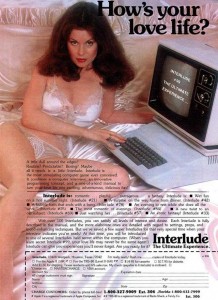

The first commercial program I know of that dealt explicitly in sex appeared in early 1980 and was called Interlude: The Ultimate Experience. You may have heard of it before; one of its marvelously kitschy advertisements made PC World‘s “25 Funniest Vintage Tech Ads” list a few years ago, and got some general Internet exposure as a result.

As indicated by the female models in its ads, Interlude was marketed toward the males who were much more likely to own computers and buy software, yet it was at least ostensibly for couples. The idea here is that each partner tells the program what sort of mood he or she is in, and the program then directs the couple to a section of an accompanying booklet that contains the perfect experience to satisfy them both, delivered in instructions to one or both. The experiences are fairly typical sex-manual fantasies. This being a family blog, here’s one of the least explicit:

Surprise your lady with roses… but not in the usual way. Buy several dozen roses. While your lady is taking a bath, scatter the rose petals over the sheets. When she comes from her bath, lay her down in a bed of roses and make love amid the fragrance.

For contrary sorts like me, some of the best fun is to be had by playing both male and female, telling the program they are in wildly incompatible moods, and watching it desperately struggle to come up with something — as in, saying the man wants to cuddle and talk and the woman wants to act out a rape fantasy. (“One of the most common female fantasies is rape — being taken by force against her will,” the booklet helpfully tells us. “She doesn’t really want to be raped,” it continues; good to know.) The dirty little secret about Interlude is that its simple computer component is not really doing anything a printed questionnaire couldn’t do. In the end, it’s an ordinary couple’s manual with an accompanying computer program that’s really just a convenience; the whole project could have been implemented using nothing more high-tech than print without too much difficulty.

A year or so after Interlude, Scott Adams’s Adventure International unveiled a pair of real sex games, at least of sorts: Strip Dice and Concentration. The catalog says that they “vaguely resemble the time-tested games on which they are based.” Actually there’s no “vaguely” about it; each is a simple BASIC implementation of an old party game which occasionally tells the loser(s) to remove articles of clothing. A prominent disclaimer on the package states, “NOTE: CONTAINS EXPLICIT SEXUAL DIALOGE [sic] WHICH MAY BE OFFENSIVE TO SOME USERS!!!!” That’s not really true either; I don’t think terms like “tush” were considered X-rated even in 1981. Again, one has to ask just what the computer really adds to the equation. Presumably most couples or libertine partygoers are capable of keeping track of what articles of clothing are still in play, as it were, and which should be removed next. Visual evidence alone should allow for that. Isn’t that sort of the whole point of the endeavor?

Another potential problem with both Interlude and the AI games is that they are aimed at couples who will presumably use them to have real sex. Plenty of computer owners inevitably lacked a better half, and were perhaps looking for more, shall we say, solo pursuits. Unfortunately, that was a problematic proposition. It was very difficult to portray an image even remotely arousing using the microcomputer display technology of the early 1980s; even ASCII art, for all the dedication of its practitioners, had its limitations. Thus visual representations of sex in gaming were limited to the most cartoonlike of portrayals that played for adolescent giggles rather than attempting the hopeless task of actually arousing anyone — stuff like the famously awful and utterly tasteless Atari 2600 game Custer’s Revenge, in which the player’s goal is to rape a Native American woman. (The company behind Custer’s Revenge, Mystique, actually published a whole line of “adult” games, each of which strives in its own way to be just as offensive.)

But what about text adventures? Certainly textual erotica had been a thriving literary genre for centuries. What looked promising on the surface was, however, much more problematic when examined in depth. Even presuming the existence of authors with the skill to make their subject matter come to life, the technology of 1981 did not permit anything like a realistic, erotic interactive sexual encounter. Sex after all involves people, and text adventures — even the very best ones, such as Zork — necessarily built deserted virtual worlds filled with inanimate objects and, perhaps here and there, people that behaved like inanimate objects. (Which does I guess give the phrase “objectification of women” a whole new meaning…) The author of the first widely distributed text adventure to deal in sex therefore wisely decided to play it for laughs. And even that, like so much else in the young industry, happened sort of by accident.

Chuck Benton was living in a small town near Boston and working as a field engineer for a New England flight-simulator manufacturer when he, like increasing numbers of other young tech-savvy people with disposable income, purchased an Apple II in 1980. Also like so many others, Benton quickly found himself entranced with his new toy. Amongst his favorite games were the Scott Adams adventures.

As he grew more familiar with his home computer’s capabilities, Benton started to notice how laborious many of the administrative processes at his job currently were, especially those used to schedule and track the field-engineering group of which he was a member. He began to evangelize the Apple II with his superiors as a way to save huge amounts of time and drudgery. In the end he perhaps got more than he bargained for: not only did management decide to buy their own Apple II for the business, but they offered Benton the chance to program a customized scheduling application to run on it. Being an ambitious sort, Benton agreed — and then wondered just what he had gotten himself into. He was an engineer by trade, with little background in programming. Now he needed to learn BASIC as quickly as possible. He decided that learning by doing is best, and that the best approach would therefore be to create a more modest learning program that would nevertheless require many of the skills his company’s application would require. After a bit more thought, he decided that a text adventure would be just about ideal. He would design it in such a way that it would require extensive file access, just like his company’s application, and make his design large enough to require him to write and structure quite a few lines of code without being so large as to be uncompletable in the few months he allocated for the project. Besides, he liked playing text adventures, and liked the idea of creating one of his own.

Benton was hardly unique in proceeding through this thought process to arrive at a text-adventure project. You may remember that Scott Adams, the reigning king of microcomputer adventure games at the time, had originally started on Adventureland as an exercise in learning BASIC and learning how to manipulate strings. A whole generation of books and articles that followed advertised text-adventure programming as a fun way to learn the art and science of programming in general. What was unique was the subject matter that Benton chose for his learning game. Instead of writing about dungeons and dragons or even rockets and rayguns, he decided to write about his own experiences as a single guy in his late 20s trying to navigate the Boston night life, have a good time, and, yes, hopefully get laid every once in a while. Why not? He was just writing the game for fun and for education. Maybe he would share it with a few buddies, but that was it.

After working on the game for a couple of months, though, Benton couldn’t help but notice that said buddies really, really liked the game. They found it hilarious, and were always asking how it was coming along and whether they could play the latest version. Benton was well aware of others, like the Williams and for that matter Scott Adams himself, who were making real money selling text adventures. And certainly he had a game with what could only be described as its own unique appeal. The wheels turned, until Benton made the decision to forget about the idea of the game as a modest training exercise and develop it into a complete, polished work he could try to sell. He abandoned the current, patched-together version and started over from scratch with a more rigorous approach.

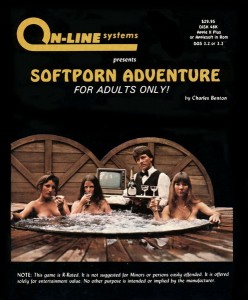

As he cleaned up the game’s underlying technology, he also cleaned up the content somewhat in the realization that, while he might be able to market a risque game, as a self-described “conservative New Englander” there were limits to how far he wanted to push the envelope. Benton excised almost entirely one part of the plot, involving drugs and and a drug dealer; only a relatively innocuous magic mushroom was allowed to stay. And what had started out with the working title of Super Stud Adventure was given the gentler — and much more clever — title of Softporn Adventure. The former part of the title was a play on the habit of working “Soft” into the title of anything and everything computer-related in those days: Microsoft, DataSoft, CompuSoft, Applesoft, Softalk, Softline, etc. Why not Softporn? As for the Adventure, well, this was still a time when Benton’s major model, Scott Adams’s Adventure International, appended that word to every adventure game as a matter of course: Pirate Adventure, Mission Impossible Adventure, etc.

With this revised version of the game complete after about four or five months of work, it was now time to consider how to go about selling it. Benton guessed that few or no publishers would want to touch the game due to its content, so he decided to try to sell it himself, adopting for the purpose the company name Blue Sky Software. Like so many before him, he improvised packaging using Ziploc baggies, colored paper, and a mimeograph machine, and just like that he was in business. However, Benton’s efforts were not rewarded with the immediate success that had greeted Adams or the Williams. Part of his problem was unique to Softporn: the obvious way to advertise a new piece of software was to take out advertisements in magazines, but virtually all of them were too spooked by the content (not to mention the title) of Softporn to take Benton’s money. But in addition, the road Benton had chosen was becoming a much harder one by this point, early 1981. In establishing the first proper software distributor, Ken Williams had, even as he made it easier for established publishers to get their products into stores, made it much harder for lone wolves like Benton, who lacked connections and distribution agreements with the likes of Softsel, to get their software noticed and available in the rapidly expanding retail-computer ecosystem. Ken had in other words made it much harder for others to do what he had done with Mystery House; an historic window of opportunity was slowly closing as business-as-usual moved in. Luckily, it was also Ken that rode to Benton’s rescue.

On June 6, 1981, the first computer show devoted exclusively to Apple products, AppleFest, took place in Boston. Figuring that at least here no prudish press could get between him and potential customers, Benton rented space to try to drum up some attention and sales for Softporn. Also there, in much more prominent fashion, were Ken Williams and his rapidly growing company On-Line Systems. Wandering the show floor, Ken came across Benton’s little display, chatted briefly with its owner, and bought a copy of Softporn to take back to California with him. The game became a huge hit amongst Ken and his staffers; they thought it a “riot.” Ken of course knew that any attempt to market the game would lead to mass controversy, but he also understood well the old maxim that any publicity is good publicity, particularly when trying to get an empire off the ground. Besides, he thought the controversy would be “fun,” in a time when On-Line Systems was still young and freewheeling enough that that counted as a valid argument. And with major and growing clout in the software industry, Ken felt On-Line would be able to overcome the qualms of magazines and retailers where Benton had failed, and thereby get the game noticed and get it onto shelves. Within days Ken called Benton to ask him if he would let On-Line Systems publish his game. For Benton, just about ready to give up on the idea of making anything at all from Softporn, Ken’s call out of the blue was like an answered prayer. He of course said yes, and On-Line set to work to make it happen.

Ken toyed with the idea of revising the game to fit into On-Line’s Hi-Res Adventures line with the addition of graphics, but that would take considerable time, and would of course also open the whole new can of worms of trying to decide just what level of visual explicitness would be appropriate. So he shelved the idea of a graphical Softporn, although, as those familiar with later history know, never quite abandoned it. For now, he decided, the game was fine as-is.

Ken may have been happy with the game itself, but he wasn’t impressed with Benton’s simple homemade packaging. He felt it needed artwork that made a… bolder statement of intent. The endgame of Softporn involves a beautiful woman and a hot tub, and that gave the jacuzzi-loving Ken all the inspiration he needed. He convinced three women at the company to come to his house for a topless photo shoot in his hot tub. This being On-Line Systems, where nepotism ruled, all were married to men also working at the company. There was Dianne Siegel, a technician and eventual production manager who was married to head accountant Larry Bain; the wife of Bob Davis of Ulysses and the Golden Fleece fame, who worked in accounting; and, most famously, Roberta Williams herself. Ken hired to join them a waiter from the only decent restaurant in town, a steakhouse with a name ironically appropriate for the local economy On-Line was rapidly transforming: The Golden Bit. This fellow was flamboyantly gay and thus considered an acceptable risk to join the three topless wives in the hot tub. The final touch of kitsch came from an Apple II presumably acting as master of ceremonies to the sexy proceedings.

As a generation of teenage boys would soon discover, the photo promised much, much more than the actual game delivered. But then that was already becoming something of a tradition in computer-game packaging, where countless luridly drawn dragons battled knights in armor in scenes that showed little obvious connection to the sparsely rendered virtual worlds found inside the boxes. In the long run this particular picture became more famous than anything in the game it promoted, the enduring icon of this wild early era in On-Line’s history.

With the photo taken, Ken put it and Benton’s game out there within weeks of that initial phone call. He then settled back and waited for the controversy to ensue. We’ll get to that, and have a look at the contents of the game itself (something that oddly almost always goes undone in discussions of Softporn), next time.

(Along with John Williams and the gift that just keeps on giving, Steven Levy’s Hackers, Jason Scott’s interview with Chuck Benton for Get Lamp provided much of the material on Softporn for this article and the next.)