If you want to understand how different the computer world of 1981 was from that of today, a good place to look is the reception of Silas Warner’s programming game, Robot War. It received big, splashy feature articles in Softalk, the early flagship of the Apple II community, as well as the premiere issue of Computer Gaming World, one of the first two computer magazines unabashedly dedicated just to games. (Softline, a spinoff of Softalk, edged it out by just a hair for the prize of first.) In the only metric that ultimately matters to a publisher, it even bounced on and off of Softalk‘s monthly lists of the top 30 Apple II software bestsellers for a year or so. All this for a “game” that involved a text editor, a compiler, and a debugger — a game that sounds suspiciously like work to modern ears. But in 1981 the computer world was still a comparatively tiny one, and virtually everyone involved knew at least a little bit of programming as a prerequisite to getting anything at all done; most home computers booted directly into BASIC, after all. More abstractly, even the hardcore gamers (not that that term had yet been invented) were as fascinated with the technology used to facilitate their obsession as they were with games as entities unto themselves. In this milieu, a programming game didn’t sound like quite such an oxymoron.

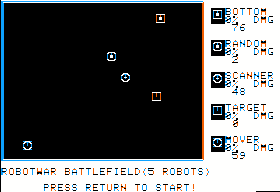

Robot War was by far the most ambitious game Silas had yet created for Muse, a dramatic departure from simple BASIC excursions like Escape! Not coincidentally, it was also the first he created after finally agreeing to come to Muse Software full time in 1980. He did already have a leg up on it to start, for Robot War on the Apple II is basically the same game as the version he had programmed for the PLATO system a few years before. It does, however, offer some enhancements, most notably the ability for up to five robots to battle one another at one time in a huge free for all; the original had offered only one-on-one matches.

While they didn’t approach software development as systematically as did Infocom, Muse had developed some unusually sophisticated tools by this stage to make assembly-language coding a less arduous task. At a time when other shops seemed to accept perpetual reinventing of wheels as a way of life, Muse had also gotten quite good at reusing its code wherever possible. Large chunks of Robot War, for instance, are lifted straight out of Super-Text, the company’s word processor. One edits one’s source code in a streamlined version of Super-Text itself. Employing one of the strangest criteria for recommending a game ever, Softalk noted that playing Robot War makes “learning the real Super-Text a snap.”

The other way that Super-Text helped beget Robot War is more surprising, and gives me the opportunity to make one of my little lessons in technology — specifically, computer display technology.

The screen on which you’re reading this is almost certainly a bitmapped display. This means that it is seen by the computer as just a grid of colored pixels. The text you’re reading is mapped onto that grid in software, “drawn” there like an unusually intricate picture. This is a cool thing for many reasons. For one, it allows you to customize things like the size, shape, and style of the default font to suit your own preferences. For another, it allows writers like me to play with different typefaces to get our message across. It’s a particularly nice thing for word processing, where a document on the screen can be rendered as a perfect — or at least nearly perfect — image of what will appear when you click “Print.” (We call this what-you-see-is-what-you-get, or WYSIWYG). It’s also got some disadvantages, however: rendering all of that text letter by letter and pixel by pixel consumes a lot of processing power, and storing that huge grid of pixels consumes a lot of memory. The screen on which I’m writing this is 1920 X 1200 pixels. At the 4 bytes per pixel needed to display all the colors a modern computer offers — another, separate issue — that amounts to about 9 MB. That number is fairly negligible on a machine with 4 GB of memory like this one, but on one with just 48 K like the Apple II, even accounting for the need to store vastly fewer colors and a vastly lower resolution, it can be a problem. So, the standard, default display mode of the Apple II is a textual screen, stored not as a grid of individual pixels but as a set of cells, into each of which a single letter or a graphical glyph — essentially a “letter” showing a little glyph which can be combined with others to draw frames, diagrams, or simple pictures — can be inserted. Rendering these characters to the screen is then handled in the display hardware rather than involving any software at all. This approach has plenty of disadvantages: one is limited to a single font; said font must be mono- rather than variable-spaced; changing the font’s size or style are right out; etc. On the plus side, it’s fast and it doesn’t use too much memory. In fact, the Apple II was unique among the trinity of 1977 in offering a bitmapped graphics mode at all; the TRS-80 and PET offered only character-oriented displays. The Apple II’s Hi-Res mode is much of the reason it stood out so amongst its peers as the Cadillac of early microcomputers.

One would naturally expect a word processor — about the most text-oriented application imaginable — to work in the Apple II’s text mode. As Ed Zaron of Muse was developing Super-Text, however, he had to confront a problem familiar to makers and users of much early Apple II application software. The Apple II’s text mode could display just 40 big, blocky characters per line. Amongst other reasons, this design decision had been made because the machine’s standard video feed was just an everyday, fairly low-quality analog television signal. Trying to display more, smaller characters, especially on the television many users chose in lieu of a proper monitor, would just result in a bleeding, unreadable mess. The problem for word processing and other business applications was that a standard typewritten page has 80 characters to a line. Thus, and even though the word processor was not going to be anything close to WYSIWYG under any circumstances given the other limitations of the Apple II’s display, it was even harder than it might otherwise be for the user to visualize what a document would look like in hard copy while it was on the screen, what with each hardcopy line spread over two onscreen. Zaron therefore considered whether he might be able to use Hi-Res mode to display 80 characters of text, at least for those whose displays were good enough to make it readable.

The problem with that idea, however, was that the Apple II has no built-in ability to render text to the Hi-Res screen. One can paint individual pixels, even draw lines and simple shapes, but there is no facility to tell the machine to, say, draw the letter “A” at position 100 X 100. Zaron therefore spent considerable time developing a Hi-Res character generation of his own — a program that could essentially render little pictures representing each glyph to the screen on command, just as your display works today. Zaron and Muse ultimately decided the idea just wasn’t viable for Super-Text. Even with a good monitor it was just too ugly to work with for long periods of time given the color idiosyncrasies of Hi-Res mode, and it was unacceptably slow to work with for entering and editing text. Besides, by that time something called the Sup’R’Terminal was available from a company called M&R Enterprises. This was a card which plugged into one of the Apple II’s internal slots (bless Woz’s foresight!) and solved the problem by adding an entirely new, alternate display system that could render 80 columns of text quickly and cleanly. It also solved another problem for word processors in being able to render lower-case as well as upper-case text (the original Super-Text had had to distinguish upper case from lower case by highlighting the former in reverse video). Soon enough an array of similar products would be available, eventually including some from Apple itself. So, Zaron’s character generator went on the shelf…

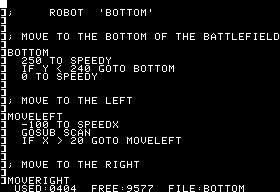

…to be picked up by Silas Warner and incorporated into Robot War. While plenty of games made use of the Apple II’s split-screen mode which allowed a few lines of conventional text to appear at the bottom of a Hi-Res display, the screenshot above is one of the few examples in early Apple II software of dynamically updated text being incorporated directly into a Hi-Res display, thanks to Zaron’s aborted Super-Text character generator. Sometimes software development works in crazy ways.

Even if you aren’t a programmer, the idea of Robot War — of programming your own custom robot, then sending him off to do battle with others while you watch — is just, well, neat. That neatness is a big reason that I can’t resist taking some time to talk about it here, where we’re usually all about the ludic narrative. Of course, given the technological constraints Silas was working with there are inevitable limits to the concept. You don’t get to design your robot in the physical sense; each is identical in size, in the damage it can absorb, in acceleration and braking, and in having a single rotatable radar dish it can use to “see” and a single rotatable gun it can use to shoot. The programming language you work with is extremely primitive even by the standard of BASIC, with just a bare few commands. Actual operation of the robot is accomplished by reading from and writing to a handful of registers. That can seem an odd way to program today — it took me a while to wrap my mind around it again after spending recent months up to my eyebrows in Java — but in 1981, when much microcomputer programming involved PEEKing and POKEing memory locations and hardware registers directly, it probably felt more immediately familiar.

Here’s a quick example, one of the five simple robots that come with the game.

;SAMPLE ROBOT 'RANDOM'

] 250 TO RANDOM ;INITIALIZE RANDOM — 250

MAXIMUM

]

]START

] DAMAGE TO D ;SAVE CURRENT DAMAGE

]

]SCAN

] IF DAMAGE # D GOTO MOVE ;TEST — MOVE IF HURT

] AIM+17 TO AIM ;CHANGE AIM IF OK

]

]SPOT

] AIM TO RADAR ;LINE RADAR WITH LAUNCHER

] IF RADAR>0 GOTO SCAN ;CONTINUE SCAN IF NO ROBOT

] 0-RADAR TO SHOT ;CONVERT RADAR READING TO

]DISTANCE AND FIRE

] GOTO SPOT ;CHECK IF ROBOT STILL THERE

]

]MOVE

] RANDOM TO H

] RANDOM TO V ;PICK RANDOM PLACE TO GO

]

]MOVEX

] H-X*100 TO SPEEDX ;TRAVEL TO NEW X POSITION

] IF H-X>10 GOTO MOVEX ;TEST X POSITION

] IF H-X ] 0 TO SPEEDX ;STOP HORIZONTAL MOVEMENT

]

]MOVEY

] V-Y*100 TO SPEEDY ;TRAVEL TO NEW Y POSITION

] IF V-Y>10 GOTO MOVEY ;TEST Y POSITION

] IF V-Y ] 0 TO SPEEDY ;STOP VERTICAL MOVEMENT

] GOTO START ;START SCANNING AGAIN

]

Let’s just step through this quickly. We begin by plugging 250 into the RANDOM register, which tells the robot we will expect any random numbers we request to be in the range of 0 to 249. We store the value currently in the DAMAGE register (the amount of damage the robot has received) into a variable, D, for safekeeping. Immediately after we test the DAMAGE register against the value we just stored; if the former is now less than the latter, we know we are taking fire. Let’s assume for the moment this is not the case. We therefore add 17 to the AIM register, which has the effect of rotating our gun 17 degrees around a 360-degree axis. We send a pulse out from our radar dish in the same direction that the gun is now facing. If the radar spots another robot, it will place a number representing the negation of its distance from us into the RADAR register; otherwise it places a 0 or a positive number there. (Yes, this seems needlessly unintuitive; Silas presumably had a good technical reason for doing it this way.) If we do find a robot, we fire the gun by placing the absolute value of the number stored in RADAR into the SHOOT register. This fires a shell set to explode that distance away. We continue to shoot as long as the robot remains there. When it is there no longer, we go back to scanning the battlefield for targets.

Should we start taking fire, we need to move away. In accordance with our name, we decide this by storing random numbers from 0 to 249 — the battlefield is grid of 256 X 256 — into two variables representing our desired new horizontal and vertical positions, H and V. What follows gets a little bit more tricky. The SPEEDX and SPEEDY registers represent horizontal and vertical movement respectively, with negative numbers representing movement to the left or upward and positive numbers to the right or downward. For an added wrinkle, we can only accelerate or decelerate 40 units per second, regardless of what we place in these registers. So, we’re figuring out the relative distance and direction of our goal to our current position, which we find by reading registers X and Y, then moving that way by manipulating SPEEDX and SPEEDY. Because this is not a terribly sophisticated robot, we move into position on each axis individually rather than trying to move on a diagonal. Once we have reached our (approximate) goal, we settle down to scan and shoot once more.

So, what you’re really doing here is writing an AI routine of the sort that someone making a game from scratch might program. If nothing else, that makes it a great training tool for a prospective game programmer. Although one can have some fun playing against the robots that come with it, Robot War is really meant to be a multiplayer game, where one places one’s creations up against those of others. It begs for some sort of tournament, and in fact that’s exactly what happened; Computer Gaming World was so enamored with Robot War that they sponsored a couple in partnership with Muse. For each, several Apple IIs spent several weeks in the basement of Muse’s office/store crunching through battles to determine an eventual champion. I was intrigued enough by the idea to consider proposing a tournament here with you my gentle readers, but upon spending some time with the actual software I tend to think it’s just too crusty and awkward to modern sensibilities to garner enough interest. If you think I’m wrong, though, tell me about it in comments or email; if there’s real interest I’m happy to reconsider. Regardless, here’s the Apple II disk image and the manual for you to have a look at.

In common with another Silas Warner game of 1981, Robot War had a cultural impact far beyond what its sales figures might suggest. It was common enough even in 1981 for computer programs to model the real world, in the form of flight simulators, war games, etc. The subject matter of Robot War, however, went in the opposite direction when something called the “Critter Crunch” took place in Denver in 1987. Today real-world robot combat leagues are kind of a big deal, with their matches often televised and given exposure that any number of human sports would kill to have. I can’t say all of this wouldn’t have started without Silas Warner’s game, but it’s perhaps more than just coincidence that two of the first sustained robot-combat leagues were called Robot Wars, as were a couple of the robot-combat television series (one of which, ironically, turned back into a videogame series). Even more definitive is the influence Robot Wars exerted on the programming games that followed it. The most obvious direct homage is Robot Battle, but there’s plenty of the Robot War DNA in more mainstream efforts like MindRover, not to mention plenty of free hacker-oriented programming games which may or may not involve actual robots. And to think that Robot War was just Silas Warner’s second most influential game of a prodigious 1981…

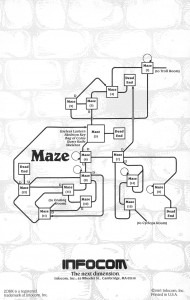

We’ll get to that other game, which actually bears more directly on this blog’s usual obsessions, soon. First, though, I want to grab one of these other balls I’ve got in the air and check in with one of our old friends.