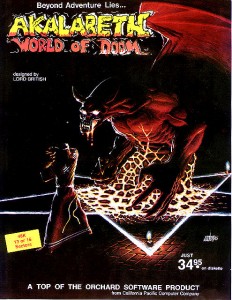

There are two conflicting stories about how the game that Richard Garriott sold in that Houston-area ComputerLand store made it to the West Coast offices of California Pacific, one of the most prolific and prominent of early Apple II software publishers. One says that the man who had prompted Garriott to start selling Akalabeth in the first place, ComputerLand manager John Mayer, did him a second huge favor by sending a copy of the game to CP for their consideration. The other says that the game got to CP’s offices within a few weeks of appearing in that ComputerLand via software-piracy channels. The latter story is the one Richard himself tells today, and, for what it’s worth, the one I tend to subscribe to. Perhaps the former was invented closer to the events themselves, to avoid anyone having to explain just how pirated software made its way into CP’s offices. However Akalabeth came to their attention, CP’s founder, Al Remmers, called Richard before the summer of 1980 was out, offering to fly him to Davis, California, to discuss a publication contract that would give Akalabeth nationwide distribution.

In those days game designers and programmers (almost always embodied in the same person) who could push the envelope conceptually and technically were worshiped within the still small but rapidly growing community of Apple II users. Amongst the most prominent of these was the star in CP’s stable, Bill Budge, who made his name during 1979 and 1980 with a series of frenetic action games considered remarkable for their graphics. Garriott, like any engaged Apple II user, knew Budge’s work well, so much so that his first reaction on getting the call was amazement that his work could be considered worthy by the publisher of the great Budge. He made the trip to California with nervous parents in tow, who wanted to be sure their son would not be ripped off by the fast-talking Remmers. They found no grounds for concern, and the deal was quickly done.

It was Remmers, who could show a keen promotional instinct when the mood struck him, that suggested they credit the game not to Richard Garriott but only to his in-game alter ego, Lord British, starting a tradition that would persist for many years. Upon Akalabeth‘s CP release, probably in late October or November of 1980, Remmers orchestrated a contest with Softalk magazine, in which the magazine would publish a series of cryptic clues from which readers were expected to guess Lord British’s real identity:

Lord British is not a member of the Silicon Gulch.

Lord British attends the largest university in the state of friendship.

He and his home city are closely related to present and future blastoffs.

He works at a store on the King’s Highway near the city of the clear lake in the land of computers.

ComputerLand knows him as the Son of Skylab I and if you call you’ll know him too.

No one who wasn’t already a Richard Garriott acquaintance managed to decipher the clues, and the contest fizzled out rather anticlimactically with a series of consolation prizes for things like most imaginative solution methodology in Softalk‘s May, 1981, issue. The following issue featured a full profile of Garriott that revealed all at last. Still, yet another thing that would follow Garriott throughout his career, his larger-than-life persona in the computer press as Lord British, was now in place, and once again largely accidentally, at the behest of others. Truly the young Richard Garriott led a charmed life.

While Akalabeth and Garriott did receive considerable press thanks to Remmers’s cozy relationship with Softalk, the question of its actual sales is one I can’t quite consider settled. Garriott himself recently reiterated in this blog’s comments a claim he has often made, that Akalabeth sold some 30,000 copies and netted for its author at least $150,000. There are however, several pieces of admittedly circumstantial evidence that do tend to pull against this a bit.

As a point of comparison, we might take a game I discussed earlier in this blog, On-Line Systems’s The Wizard and the Princess. According to official histories from Sierra (the company that On-Line Systems morphed into), this game eventually sold 60,000 copies. However, in the September/October, 1982, issue of Computer Gaming World, we find a list of the top sellers of various game publishers as of June 30, 1982. There, The Wizard and the Princess is listed as having sold just 25,000 copies by that date, almost two years after its release. That’s surprising, but not untenable; the microcomputer industry was growing so quickly in the early 1980s that sales even of older games could increase month by month and even year by year simply because there were so many new consumers always coming online to buy them. So, let’s run with The Wizard and the Princess as a 25,000-copy seller through mid-1982. As I noted in an earlier post, The Wizard and the Princess was a perennial on Softalk‘s best-seller top ten for well over a year after its release, spending much of that time in the top five. Akalabeth, by contrast, made just two appearances in the top 30, appearing in the January, 1981, list at number 23 and then disappearing for two months, only to bubble up one last time at number 26 in the April issue. Given that Akalabeth would permanently disappear from shelves in 1982 for reasons we’ll get to down the road a bit, and thus would not be able to benefit from the long tail of new consumers that presumably benefited The Wizard and the Princess, this is hard to reconcile with the idea that Akalabeth outsold The Wizard and the Princess by 5000 copies between the former’s late 1980 release and mid-1982.

On that same mid-1982 Computer Gaming World list, California Pacific claims Garriott’s next game, Ultima, as its own top seller, with sales of — and this is interesting — just 20,000 copies. And then there is a question that’s been raised in vintage-software-collector circles: if 30,000 copies of Akalabeth were sold, where are they? The California Pacific Akalabeth (let’s not even talk about the ComputerLand version) remains exceedingly rare, much more so than other titles of similar vintage which allegedly sold in much smaller numbers.

Now, it’s very true that objections could be raised to many of these points. Softalk‘s sales listings, for instance, were generated by surveying “Apple-franchised retail stores representing approximately 15 percent of all sales of Apple and Apple-related products [who] volunteered to participate in this poll.” Notably, mail-order sales were not considered at all. Since it deals only in ratios, not absolute numbers, Softalk‘s editors assumed the poll to be a valid reflection of the Apple II software market in general, but perhaps this assumption did not entirely hold true. Even the Computer Gaming World list was generated by simply asking the various publishers. It’s entirely possible that, due to conscious deception, confusion that grew from an admittedly rather poorly worded premise, or simple mistakes, some of these numbers are inaccurate — perhaps dramatically so. And I do want to emphasize again that, if the 30,000-copy figure is not correct, I certainly don’t attribute the confusion to deliberate deception on Garriott’s part — merely to 30-year-old events and poor record keeping in a software industry that, as we’ll see all too clearly when we get to later events in Garriott’s career, was not exactly a model of responsible business practice.

Whatever its sales figures, we can feel confident that Akalabeth generated a nice chunk of money for its starving-student creator. Garriott has characterized this time in the software industry as the “free money era,” during which even programs that frankly weren’t very good could generate a lot of money for their creators — such was the demand for new software, any software among new minted Apple II zealots. CP sold Akalabeth for $35 (up from the $20 Garriott had charged at ComputerLand). Accounting for inflation, this figure puts it right in line and then some with a hot new AAA console title of today. CP was known for offering a very generous royalty rate to its developers, often as high as 50%. Garriott presumably gave a little something to his title-screen artist Keith Zabalaoui, but the rest was all his. Even if Akalabeth didn’t sell anywhere near 30,000 copies, that adds up to one hell of a windfall for a university student. (If Garriott earned $15 per copy and Akalabeth sold even 10,000 copies, there’s your $150,000 right there.) As Garriott recently said in a lengthy interview by Warren Spector, it’s been “all downhill from there” as far as return on investment in the computer-game industry. Indeed, I find the idea that it was for at least a year or two possible to make $150,000 from a 22 K BASIC program you wrote all by yourself simultaneously exciting and vaguely horrifying. Alas, I was born ten years too late…

Even before he returned to Austin for another year of classes and SCA events, Garriott began working on another game. This one would be more ambitious than Akalabeth, his first creation conceived and written entirely on the Apple II and his first to be consciously crafted for commercial sale. We’ll get to that soon, but next I want to switch topics yet again to look at the origins of the company many of you who read this blog love more than any other.