As I write this the news media and the blogosphere are just tailing off from an explosion of commentary and retrospectives triggered by an obviously ill Steve Jobs stepping down at last from his post as Apple’s CEO. The event marks the end of an era. With Bill Gates having retired from day-to-day involvement with Microsoft a few years ago, the two great survivors from those primordial computing days of the late 1970s and early 1980s no longer run the iconic companies that they began to build all those years ago.

For many, Bill and Steve embodied two fundamentally opposing approaches to technology. On one side was Gates, the awkwardly buttoned-down overachiever who never even as a multi-billionaire seemed quite comfortable in his own skin, wielding spreadsheets and databases while obsessing over Microsoft’s latest financial reports. On the other was Jobs, the epitome of California cool who never met a person he couldn’t charm, wielding art packages and music production software while talking about how technology could allow us to live better, more elegant lives. These attitudes were mirrored in the products of their respective companies. In In the Beginning Was the Command Line, Neal Stephenson compared the Macintosh with a sleek European sedan, while Windows was a station wagon which “had all the aesthetic appeal of a Soviet worker housing block; it leaked oil and blew gaskets, and [of course] it was an enormous success.” These contrasts — or should we say caricatures? — run deep. They were certainly not lost on Apple itself when it made its classic series of “I’m a Mac / I’m a PC” commercials to herald its big post-millennial Jobs-helmed comeback.

Even in the late 1970s, when he was a very young man, Jobs had an intuitive feeling for the way that technology ought to work and an aesthetic eye that was lacking in just about every one of the nerds and hackers that made up the rest of the early microcomputer industry. Almost uniquely among his contemporaries, Jobs had a vision of where all this stuff could go, a vision of a technological future that would appeal not just to PC guy in the commercials above but also to Mac guy. The industry desperately needed a guy like Jobs — good-looking, glib, articulate, with an innate sense of aesthetics and design — to serve as an ambassador between the hackers and ordinary people. Jobs was the kind of guy who might visit a girlfriend’s home for dinner and walk away with a check to fund his startup business from the father and a freshly baked cake from the mother. He made all these hackers with their binary code and their soldering irons seem almost normal, and almost (if only by transference) kind of cool.

There’s a trope that comes up again and again amongst the old-timers who remember those days and the histories that are written of them: that it was a fundamentally innocent time, when hackers hacked just for the joy of it and accidentally created the modern world. In Triumph of the Nerds, Jobs’s partner in founding Apple, Steve Wozniak, said:

“It was just a little hobby company, like a lot of people do, not thinking anything of it. It wasn’t like we both thought it was going to go a long ways. We thought we would both do it for fun, but back then there was a short window in time where one person who could sit down and do some neat, good designs could turn them into a huge thing like the Apple II.”

I believe Wozniak, a hacker’s hacker if ever there was one. To imagine that an amity of hacking bliss united those guiding the companies that made up the early industry, though, is deeply mistaken. As shown by the number of companies and computer models that had already come and gone by even 1982, the PC industry was a cutthroat, hyper-competitive place.

In the same video, Jobs has this to say about those days:

“I was worth over a million dollars when I was 23, and over ten million dollars when I was 24, and over a hundred million dollars when I was 25, and it wasn’t that important, because I never did it for the money.”

In contrast to Wozniak’s comments, there’s a note of disingenuousness here. It seems suspicious that, for someone for whom finances are so unimportant, Jobs has such a specific recollection of his net worth at exact points in time; something tells me Wozniak would be challenged to come up with similar figures. I mentioned once before on this blog how Jobs cheated his best friend Wozniak out of a $5000 bonus for designing Breakout on his behalf for Atari. Jobs was of course a very young man at the time, and we’d all like to have things back from our youth, but this moment always struck me as one of those significant markers of character that says something about who a person fundamentally is. Wozniak might dismiss the incident in his autobiography by saying, “We were just kids, you know,” but I can’t imagine him pulling that stunt on Jobs. In another of those markers of character, Wozniak was so honest that, upon designing the computer that would come to be known as the Apple I and founding a company with Jobs to market it, he suddenly recalled the employment contract he had signed with Hewlett Packard which said that all of his engineering work belonged to HP during the term of his employment, whether created in the office or at home, and tried to give his computer design to HP. Much to Jobs’s relief, HP just looked at it bemusedly and told Wozniak to knock himself out trying to sell the thing on his own.

In the case of Jobs, when we drill down past the veneer of California cool and trendy Buddhism we find a man as obsessively competitive as Gates; both men were the most demanding of bosses in their younger days, who belittled subordinates and deliberately fomented discord in the name of keeping everyone at their competitive best. Gates, however, lacked the charm and media savvy that kept Jobs the perpetual golden boy of technology. Even when he was very young, people spoke about the “reality distortion field” around Jobs that seemed to always convince others to see things his way and do his bidding.

And if Jobs isn’t quite the enlightened New Man whose image he has so carefully crafted, there’s a similarly subtle cognitive dissonance about his company. Apple’s contemporary products are undeniably beautiful in both their engineering and their appearance, and they’re even empowering in their way, but this quality only goes so far. To turn back to Stephenson again, these sleek machines have “their innards hermetically sealed, so that how they work is something of a mystery.” Empowering they may be, but only on Apple’s terms. In another sense, they foster dependence — dependence on Apple — rather than independence. And then, of course, all of that beauty and elegance comes at a premium price, such that they become status symbols. The idea of a computing device, whatever its price, becoming a status symbol anywhere but inside the community of nerds would of course have been inconceivable in 1980 — so that’s progress of a sort, and largely down to Jobs’s influence. Still, it’s tempting sometimes to compare the sealed unknowability of Apple’s products with the commodity PCs that once allowed the “evil” Bill Gates to very nearly take over the computing world entirely. A Windows-based PC may have been a domestic station wagon or (in another popular analogy) a pickup truck, but like those vehicles it was affordable to just about everyone, and it was easy to pop the hood open and tinker. Apple’s creations required a trip to the metaphorical exotic car dealership just to have their oil changed. A Macintosh might unleash your inner artist and impress the coffee-house circuit, but a PC could be purchased dirt cheap — or assembled from cast-off parts — and set up in the savannah to control those pumps that keep that village supplied with drinking water. There’s something to be said for cheap, ubiquitous, and deeply uncool commodity hardware; something to be said for the idea of (as another microcomputer pioneer put it) “computers for the masses, not the classes.”

A mention of Linux might seem appropriate at this juncture, as might a more fine-grained distinction between hardware and software, but these metaphors are already threatening to buckle under the strain. Let’s instead try to guide this discussion back to Jobs and Woz, an odd couple if ever there was one.

Wozniak was a classic old-school hacker. Even during high school in the late 1960s, he fantasized about computers the way that normal teenagers obsessed over girls and cars. His idea of fun was to laboriously write out programs in his notebooks, programs which he had no computer to run, and to imagine them in action. While other boys hoarded girlie magazines, Woz (as everyone called him) collected manuals for each new computer to hit the market — sometimes so he could redesign them better, more efficiently, in his imagination.

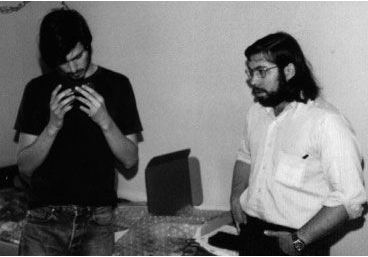

In 1970, during a working sabbatical of sorts from university, the 20-year-old Woz met the 15-year-old Steve Jobs. Despite the age difference, they became fast friends, bonding over a shared love of technology, music, and practical jokes. Soon they discovered another mutual obsession: phone phreaking, hacking the phone system to let one call long distance for free. The pair’s first joint business venture — instigated, as these sort of things always were, by Jobs — was selling homemade “blue boxes” that could generate the tones needed to mimic a long-distance carrier.

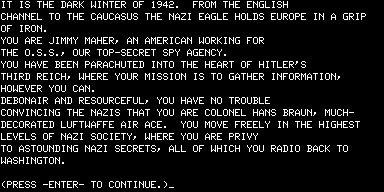

Jobs was… not a classic old-school hacker. He was, outwardly at least, a classic hippie with a passion for Eastern philosophy and Bob Dylan, a “people person” with little patience for programming or engineering. Nevertheless, the reality distortion field allowed him to talk his way into a technician’s job at rising arcade-game manufacturer Atari. He even got Atari to give him a summer off and an airline ticket to India to do “spiritual research.” In spite of it all, though, the apparently clueless Jobs just kept delivering the goods. The reason, of course, was Woz, who by then was working full-time for Hewlett Packard during the day, then doing Jobs’s job for him by night. The dynamic duo’s finest hour at Atari was the arcade game Breakout. In what at least from the outside has all the markings of a classic codependent relationship, poor Woz was told that they had just four days to get the design done; actually, Jobs just wanted to get finished so he could jet off to attend the harvest at an apple orchard commune in Oregon. (You just can’t make some of this stuff up…) Woz met the deadline by going without sleep for four days straight, and did it using such an impossibly low number of chips that it ended up being un-manufactureable. Atari engineer Al Alcorn:

“Ironically, the design was so minimized that normal mere mortals couldn’t figure it out. To go to production, we had to have technicians testing the things so they could make sense of it. If any one part failed, the whole thing would come to its knees. And since Jobs didn’t really understand it and didn’t want us to know that he hadn’t done it, we ended up having to redesign it before it could be shipped.”

But Jobs made it to the apple festival, and also got that $5000 bonus he neglected to tell Woz about to spend there. Even in 1984 Woz still believed that he and Jobs had earned only $700 for a design that became the big arcade hit of 1976.

We can really only speculate about what caused Woz to put up with treatment like this — but speculation is fun, so let’s have at it. Woz was one of those good-hearted sorts who want to like and be liked, but who, due to some failure of empathy or just from sheer trying too hard, are persistently just enough out of sync in social situations to make everything a bit awkward. Woz always seemed to laugh a little bit too loud or too long, couldn’t quite sense when the time was right to stop reciting from his store of Polish jokes, didn’t recognize when his endless pranks were about to cross the line from harmless fun into cruelty. For a person like this the opportunity to hang out with a gifted social animal like Jobs must have been hard to resist, no matter how unequal the relationship might seem.

And it wasn’t entirely one way — not at all, actually. When Woz was hacking on the project that would become the Apple I, he lusted after a new type of dynamic RAM chips, but couldn’t afford them. Jobs just called up the manufacturer and employed the reality distortion field to talk them into sending him some “samples.” Jobs was Woz’s enabler, in the most positive sense; he had a genius for getting things done. In fact, in the big picture it is Woz that is in Jobs’s debt. One senses that Jobs would have made his mark on the emerging microcomputer industry even if he had never met Woz — such was his drive. To be blunt, Jobs would have found another Woz. Without Jobs, though, Woz would have toiled away — happily, mind you — in some obscure engineering lab or other his entire life, quietly weaving his miniaturized magic out of silicon, and retired with perhaps a handful of obscure patents to mark his name for posterity.

Unsurprisingly given their backgrounds and interests, Woz and Jobs were members of the famous Homebrew Computer Club, Woz from the very first meeting on March 5, 1975. There, the social hierarchy was inverted, and it was Woz with his intimate knowledge of computers that was the star, Jobs that was the vaguely uncomfortable outsider.

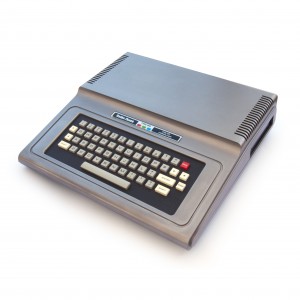

Woz designed the machine that became the Apple I just for fun. It was somewhat unique within Homebrew in that it used the new MOS 6502 CPU rather than the Intel 8080 of the original Altair, for the very good reason that Woz didn’t have a whole lot of money to throw around and the 6502 cost $25 versus $175 for the 8080. The process was almost committee-driven; Woz, who had the rare and remarkable gift of being without ego when it came to matters of design, would bring his work-in-progress to each biweekly Homebrew meeting, explaining what he’d done, describing where he was having problems, and soliciting advice and criticism. What he ended up with was pretty impressive. The machine could output to a television screen, as opposed to the flashing lights of the Altair; it used a keyboard, as opposed to toggle switches; and it could run a simple BASIC interpreter programmed by Woz himself. Woz said he “designed the Apple I because I wanted to give it away free for other people. I gave out schematics for building my computer at the next meeting I attended.”

Steve Jobs put a stop to those dangerous tendencies. He stepped in at this point to convince Woz to do what he never would have done on his own: to turn his hacking project into a real product provided by a real company. Woz sold his prized HP calculator and Jobs his Volkswagen van (didn’t someone once say that stereotypes are so much fun because they’re so often true?) to form Apple Computer on April 1, 1976. The Apple I was not a fully assembled computer like the trinity of 1977, but it was an intermediate step between the Altair and them; instead of a box of loose chips, you got a finished, fully soldered motherboard to build onto with your own case, power supply, keyboard, and monitor. The owner of an important early computer store, The Byte Shop, immediately wanted to buy 50 of them. Problem was, Jobs and Woz didn’t have the cash to buy the parts to make them. No problem; Jobs employed the reality distortion field to convince a wholesale electronics firm to give these two hippies tens of thousands of dollars in hardware in exchange for a promise to pay them in one month. Apple ended up selling 175 Apple Is over the next year, each assembled by hand in Jobs’s parents’ garage by Jobs and Woz and a friend or family member or two.

While that was going on, Woz was designing his masterpiece: the Apple II.