To say Scott Adams had a productive 1979 doesn’t begin to tell the half of it. For starters, he released a rather staggering six complete new games: Mission Impossible, Voodoo Castle, The Count, Strange Odyssey, Mystery Fun House, and Pyramid of Doom. Of these, four were the sole work of Adams himself.

Voodoo Castle was credited to Adams’s then-wife, Alexis. Still, the real situation there is muddled, as Adams has tended to downplay her contribution in recent interviews, saying that she was responsible only for the broadest strokes, leaving him to do most of the writing and all of the programming. What with the passage of years and the difficult feelings that accompany any divorce, it’s probably not possible to know anymore whether Alexis Adams deserves to be credited as the first female adventure-game designer, beating Roberta Williams to the punch by more than a year.

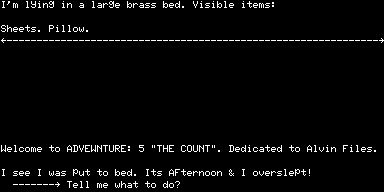

More definite is the contribution of Alvin Files to Pyramid of Doom. Working independently, with no access to source code or design documents, Files reverse-engineered Adams’s adventure-game engine, created a game of his own using it, and sent the result to Adams himself, who tweaked it a bit and released it as Adventure #8, which he acknowledges to be “90 percent” Files’s original work. Pyramid of Doom was released around October of 1979, but an early sign of the budding relationship can be seen in that summer’s The Count, which is “dedicated to Alvin Files.”

In sorting out this chronology via magazines and other primary-source documents, I was quite surprised to realize that fully two-thirds of what has come to be regarded (somewhat arbitrarily) as the canonical dozen Scott Adams adventures were created before Adams’s company, Adventure International, was even founded. Said founding occurred just before the end of the year, by which time Adams was already involved in another important step: porting his adventure engine to run on other microcomputer platforms. The logical first target for these efforts was the Apple II, the second most popular machine in 1979, but within a few years the explosion of incompatible machines and Adams’s dedication to supporting as many of them as possible would bring the games to at least a dozen different platforms. While 1979 wasn’t yet the year that adventure games broke really big, it was the year that Adams laid the groundwork for their doing so, for the changing of the calendar left him poised with a new company, a portable adventure-game engine, and a nice catalog of already extant games in a wide variety of genres. He had even created a stripped-down “sampler” version of Adventureland for those looking to test these new waters.

Even on the good old TRS-80 Adams made major technical improvements. At the apparent urging of Lance Micklus, he reimplemented his interpreter using assembly language rather than BASIC between the release of Mission Impossible in the spring of 1979 and Voodoo Castle and The Count that summer, bringing enormous speed improvements. He also implemented a new display system that would become something of a trademark, with the current room description and contents always displayed in a separate, non-scrolling “window” in the upper half of the screen. Given the TRS-80’s 64-character by 16-line display and the attendant tendency for everything of interest to scroll away in no time, this amounted to a major convenience. The new interpreter even supported lower-case output, although prose style, grammar, and even spelling remained all too obviously not a big priority. With these improvements the new system, which was quickly retrofitted back into the first three games as well, made TRS-80 adventuring a much more pleasant experience.

But what of the content of the games themselves? Well, both their limited engine and the torrid pace at which Adams cranked them out acted as a necessary limit on their scope of possibility, but there are some new developments worth talking about. Chief among them is the element of time. Both the original Adventure and Adventureland had of course required close attention to time management thanks to their expiring light sources, but Mission Impossible introduced the element in a more plot-centric way, in the form of a ticking time-bomb that threatened to destroy a nuclear power plant. And two games on from that we have The Count, a game that is about as conceptually ambitious as Adams would ever get and a significant step forward for the text adventure as a storytelling medium. I’ll look at The Count, by far the most interesting of these six efforts, in some detail next time.