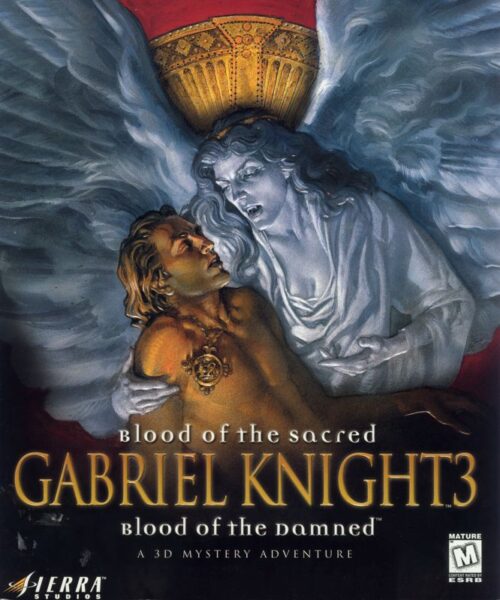

Gabriel Knight 3: Blood of the Sacred, Blood of the Damned

I think I became convinced when I went to CES [in January of 1997] and I walked around the show looking at all these titles that were the big new things, and not one screen had full-motion video. I realized that if I wanted anyone to look at the game, it had to be in 3D.

— Jane Jensen

Gabriel Knight 3: Blood of the Sacred, Blood of the Damned is proof that miracles do occur in gaming. It was remarkable enough that the game ever got made at all, in the face of gale-force headwinds blowing against the adventure genre. But the truly miraculous thing is that it turned out as well as it did. In my last article, I told you about Ultima IX, the sad-sack conclusion to another iconic series. The story of Gabriel Knight 3′s development is eerily similar in the broad strokes: the same real or perceived need to chase marketplace trends, the same unsupportive management, the same morale problems that resulted in an absurdly high turnover rate on the team. But Gabriel Knight 3 had one thing going for it that Ultima IX did not. Whereas Richard Garriott, the father of Ultima, always seemed to be somewhere else when someone might be on the verge of asking him to get his hands dirty, Jane Jensen was on the scene from first to last with her project. Just as much as the first two games, Gabriel Knight 3 managed at the last to reflect her unique vision more than some corporate committee’s view of what an adventure game should be in 1999. And that made all the difference.

In fact, I’m going to go out on a limb right here and now and deliver this article’s bombshell up-front: in defiance of the critical consensus, Gabriel Knight 3 is actually my favorite of the trilogy. As always, I don’t necessarily expect you to agree with me, but I will do my best to explain just what it is that delights, intrigues, and even moves me so much about this game.

Before we get to that, though, we need to turn the dial of our time machine back another few years from 1999, to late 1995, when Jane Jensen has just finished The Beast Within, her second Gabriel Knight game. That game was the product of a giddy but ultimately brief-lived era at Sierra On-Line, when the company’s founders Ken and Roberta Williams were convinced that the necessary future of mass-market gaming was a meeting of the minds of Silicon Valley and Hollywood: it would be a case of players making the decisions for real live actors they saw on the screen. Sierra was so committed to this future that it built its own professional-grade sound stage in its hometown of tiny Oakhurst, California. Gabriel Knight 2 was the second game to emerge from this facility, following Roberta Williams’s million-selling Phantasmagoria. But, although Gabriel Knight 2 acquitted itself vastly better as both a game and a work of fiction than that schlocky splatter-fest, it sold only a fraction as many copies. “I thought we’d done a hell of a job,” says Jensen. “I thought it would appeal to that mass market out there. I thought it would be top ten. And it was — for about a week. I watched the charts in the months after shipping and saw the games that outsold [it], and I thought, ‘Ya know, I’m in the wrong industry.'”

The underwhelming sales figures affected more than just the psyche of Jane Jensen. Combined with the similarly disappointing sales figures of other, similar games, they sent the Siliwood train careening off the rails when it had barely left the station. In the aftermath, everyone was left to ponder hard questions about the fate of the Gabriel Knight series, about the fate of Sierra, and about the fate of adventure games in general.

No offer to make a third Gabriel Knight game was immediately forthcoming. Jane Jensen took a year’s sabbatical from Sierra, busying herself with the writing of novelizations of the first two games for Roc Books. While she was away, the new, more action-focused genres of the first-person shooter and real-time strategy completed their conquest of the computer-gaming mainstream, and Sierra itself was taken over by an unlikely buyer of obscure provenance and intent known as CUC.

Thus she found that everything was different when she returned to Sierra, bubbling over with excitement about a new idea she had. During her break, she had read a purportedly non-fiction book called The Tomb of God, the latest in a long and tangled skein of literature surrounding the tiny French village of Rennes-le-Château. The stories had begun with a mysteriously wealthy nineteenth-century priest and rumors of some treasure he may have hidden in or around the village, then grown in the telling to incorporate the Holy Grail, Mary Magdalene, the Knights Templar, the Freemasons, the true bloodline of Jesus Christ, and the inevitable millennia-spanning conspiracy to control the world and hide The Truth. The bizarre cottage industry would reach its commercial zenith a few years into the 21st century, with Dan Brown’s novel The Da Vinci Code and the movie of same that followed. It’s unclear whether Jensen herself truly believed any of it, but she did see a way to add vampires to the equation — she had long intended the third Gabriel Knight game to deal with vampires — and turn it into an adventure game that blended history and horror in much the same audacious way as Gabriel Knight 2, which had dared to posit that “Mad King” Ludwig II of Bavaria had been a werewolf, then went on to make an uncannily believable case for that nutso proposition.

Sierra’s new management agreed to make the game, for reasons that aren’t crystal clear but can perhaps be inferred. It was the end of 1996, still early enough that a sufficiently determined industry observer could make the case that the failure of the adventure genre to produce any new million-selling hits of late might be more of a fluke than a long-term trend. Ken Williams was still on the scene at Sierra, albeit with greatly diminished influence in comparison to the years when he alone had called the shots. For better and sometimes for worse, he had always loved the idea of “controversial” games. The would-be Gabriel Knight 3 certainly seemed like it would fit that bill, what with being based around the heretical premise that Jesus Christ had not been celibate, had in fact married Mary Magdalene and conceived children with her in the biological, less-than-immaculate way. A few centuries earlier, saying that sort of thing would have gotten you drawn and quartered or burnt at the stake; now, it would just leave every priest, preacher, and congregation member in the country spluttering with rage. It was one way to get people talking about adventure games again.

Even so, it wasn’t as if everything could just be business as usual for the genre. The times were changing: digitized human actors were out, real-time 3D was in, and even an unfashionable straggler of a genre like this one would have to adapt. So, Gabriel Knight 3 would be done in immersive 3D, both for the flexibility it lent when contrasted with the still photographs and chunks of canned video around which Gabriel Knight 2 had been built and because it ought to be, theoretically at least, considerably cheaper than trying to film a whole cast of professional actors cavorting around a sound stage. The new game would be made from Sierra’s new offices in Bellevue, Washington, to which the company had been gradually shifting development for the past few years.

Jane Jensen officially returned to Sierra in December of 1996, to begin putting together a script and a design document while a team of engineers got started on the core technology. The planned ship date was Christmas of 1998. But right from the get-go, there were aspects of the project to cause one to question the feasibility of that timeline.

Sierra actually had three projects going at the same time which were all attempting to update the company’s older adventure series for this new age of real-time 3D. And yet there was no attempt made to develop a single shared engine to power them, despite the example of SCI, one of the key building blocks of Sierra’s earlier success, which had powered all of its 2D adventures from late 1988 on. Gabriel Knight 3 was the last of the three 3D projects to be initiated, coming well after King’s Quest: Mask of Eternity and Quest for Glory V. Its engine, dubbed the G-Engine for obvious reasons, was primarily the creation of a software engineer named Jim Napier, who set the basics of it in place during the first half of 1997. Unfortunately, Napier was transferred to work on SWAT 3 after that, leaving the technology stack in a less than ideal state.

Abrupt transfers like this one would prove a running theme. The people working on Gabriel Knight 3 were made to feel like the dregs of the employee rolls, condemned to toil away on Sierra’s least commercially promising game. Small wonder that poor morale and high turnover would be constant issues for the project. Almost 50 people would be assigned to Gabriel Knight 3 before all was said and done, but never more than twenty at a time. Among them would be two producers, three art directors, and three project leads. The constant chaos, combined with the determination to reinvent the 3D-adventure wheel every time it was taken for a spin, undermined any and all cost savings that might otherwise have flowed from the switch from digitized video to 3D graphics. Originally projected to cost around $1.5 million, Gabriel Knight 3 would wind up having cost no less than $4.2 million by the time it was finished. That it was never cancelled was more a result of inertia and an equally insane churn rate in Sierra’s executive suites than any real belief in the game’s potential.

For her part, Jane Jensen displayed amazing resilience and professionalism throughout. She had shot too high with Gabriel Knight 2, turning in a script that had to be cut down by 25 percent or more during development, leaving behind some ugly plot and gameplay holes to be imperfectly papered over. This time around, she kept in mind that game development, like politics, is the art of the possible. Despite all the problems, very little of her design would be cut this time.

The people around her were a mixture of new faces who were there because they had been ordered to be and a smattering of old-timers who shared her passion for this set of themes and characters. Among these latter was her husband Robert Holmes, who provided his third moody yet hummable soundtrack for the series, and Stu Rosen, who had directed the voice-acting cast in Gabriel Knight 1. Rosen convinced Tim Curry, who had voiced the title role in that game but sat out the live-action Gabriel Knight 2, to return for this one. His exaggerated New Orleans drawl is not to all tastes, but it did provide a welcome note of continuity through all of the technological changes the series had undergone. Recording sessions began already in November of 1997, just after Jane Jensen returned from her first in-person visit to Rennes-le-Château.

But as we saw with Ultima IX, such sessions are superficial signs of progress only, and as such are often the refuge of those in denial about more fundamental problems. When one Scott Bilas arrived in early 1998 to become Gabriel Knight 3′s latest Technical Lead, he concluded that “the engineering team must have been living in a magical dream world. I can’t find any other way to explain it. At that point, the game was a hacked-up version of a sample application that Jim Napier wrote some time earlier to demonstrate the G-Engine.” Bilas spent months reworking the G-Engine and adding an SCI-like scripting language called Sheep to separate the game design from low-level engine programming. His postmortem of the project, written for Game Developer magazine about six months after Gabriel Knight 3′s release, makes for brutal reading. For most of the people consigned to it, the project was more of a death march than a labor of love, being a veritable encyclopedia of project-management worst practices.

There was a serious lack of love and appreciation [from Sierra’s management] throughout the project. Recognition of work (other than relief upon its completion) was very rare, lacked sincerity, and was always too little, too late. Internally, a lot of the team believed that the game was of poor quality. And of course, the many websites and magazines that proclaimed “adventure games are dead” only made things worse. Tim Schafer’s Grim Fandango, although a fabulous game and critically acclaimed, was supposedly (we heard) performing poorly in the marketplace…

The low morale resulted in a lot of send-off lunches for developers seeking greener pastures. Gabriel Knight 3 had a ridiculous amount of turnover that never would have been necessary had these people been properly cast or well-treated…

After a certain amount of time on a project like this, morale can sink so low that the team develops an incredible amount of passive resistance to any kind of change. Developers can get so tired of the project and build up such hatred for it that they avoid doing anything that could possibly make it ship later. This was a terrible problem during the last half of the Gabriel Knight 3 development cycle…

Our engineers never had an accurate development schedule; the schedules we had were so obviously wrong that everybody on the team knew there was no way to meet them. Our leads often lied to management about progress, tasks, and estimates, and I believe this was because they were in over their heads and weren’t responding well to the stress. Consequently, upper management thought the project was going to be stable and ready to ship long before it actually was, and we faced prolonged crunch times to deliver promised functionality…

Most of the last year of the project we spent in [crunch] mode, which meant that even small breaks for vacations, attending conferences, and often even taking off nights and weekends were looked down upon. It was time that the team “could not afford to lose.” The irony is that this overtime didn’t help anyway; the project didn’t move any faster or go out any sooner. The lack of respect for our personal lives and attention to our well-being caused our morale to sink…

Gabriel Knight 3 became a black hole that sucked in many developers from other projects, often at the expense of those projects. Artists were shifted off the team to cut the burn rate, and then pulled back on later because there was so much work left to do…

Management, thinking that it would save time, often encouraged content developers to hack and work around problems rather than fix them properly…

All of this happened against a backdrop of thoroughgoing confusion and dysfunction at Sierra in general. A sidelined Ken Williams got fed up and left the company he had founded in August of 1997. At the end of that year, Sierra’s new parent CUC merged with another large conglomerate called HFS to create a new entity named Cendant. Just a few months later, CUC was revealed to have been a house of cards the whole time, the locus of one of the biggest accounting scandals in the history of American business. For a long stretch of the time that Gabriel Knight 3 was in the works, there was reason to wonder whether there would even still be a Sierra for the team to report to in a week or a month. Finally, in November of 1998, Sierra was bought again, this time by the French media mega-corp Vivendi, whose long-term plan was, it slowly became evident, to end all internal game development and leverage the label’s brand recognition by turning it into a publisher only. Needless to say, this did nothing for the morale of the people who were still making games there.

Sierra’s Oakhurst office was shut down in February of 1999. The first wave of layoffs swept through Bellevue the following summer, while the Gabriel Knight 3 team were striving desperately to get the game out in time for the Christmas of 1999 instead of 1998. In a stunning testimony to corporate cluelessness about the psychology of human beings, some of those working on Gabriel Knight 3 were told straight-up that they were to be fired, but not until they had given the last of their blood, sweat, and tears to finish the game. “Having a group of people who are (understandably) upset with your company for laying them off and actively looking for a job while still trying to contribute to a project is a touchy situation that should be avoided,” understates Scott Bilas. The words “no shit, Sherlock” would seem to apply here.

But the one person who comes in for sustained praise in Bilas’s postmortem is Jane Jensen, whose vision and commitment never wavered.

Gabriel Knight 3 would have simply fallen over and died had we had a less experienced designer than Jane Jensen. Throughout the entire development process, the one thing that we could count on was the game design. It was well thought-out and researched, and had an entertaining and engrossing story. Best of all, Jane got it right well in advance; aside from some of the puzzles, nothing really needed to be reworked during development. She delivered the design on time and maintained it meticulously as the project went on.

This was Gabriel Knight 3′s secret weapon, the thing that prevented it from becoming a disaster like Ultima IX. With Jane Jensen onboard, there was always someone to turn to who knew exactly what the game was meant to do and be. The vision thing matters.

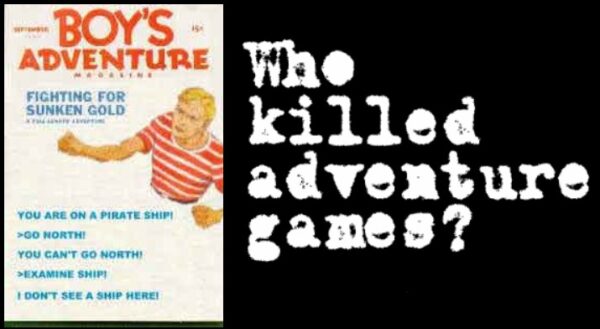

When Gabriel Knight 3: Blood of the Sacred, Blood of the Damned shipped in November of 1999, it marked the definitive end of an era, being the last Sierra adventure game ever, the final destination of a cultural tradition that stretched all the way back to Mystery House almost twenty years before, to a time when the computer-game industry was more inchoate than concrete. During the graphic adventure’s commercial peak of the early 1990s, Sierra and LucasArts had been the yang and the yin of the field, the bones of endless partisan contentions among gamers. It’s therefore intriguing and perhaps instructive to compare the press reception of Gabriel Knight 3 with that of 1998’s Grim Fandango, the most recent high-profile adventure release from LucasArts.

Grim Fandango was taken up as a sort of cause célèbre by critics, who rightly praised its unusual setting, vividly drawn characters, and moving story, even as they devoted less attention to its clumsy interface and convoluted and illogical puzzle structure. Those who wrote about games tended to be a few years older on average than those who simply played them. Many of this generation of journalists had grown up with Maniac Mansion and/or The Secret of Monkey Island. They were bothered by the notion of a LucasArts that no longer made adventure games, and sought to make this one enough of a success to avoid that outcome. At times, their reviews took on almost a hectoring tone: you must buy this game, they lectured their readers. The pressure campaign failed to fully accomplish its goal; Grim Fandango wasn’t a complete flop, but it did no more than break even at best, providing LucasArts with no particularly compelling financial argument for making more games like it.

Alas, when it arrived a year later, Gabriel Knight 3 was not given the same benefit of the doubt as to its strengths and weaknesses. Some of the reviews were not just negative but savagely so, almost as if their writers were angry at the game for daring to exist at all in this day and age. GameSpot pronounced this third installment fit “only for the most die-hard fans of the series.” Even the generally sober-minded Computer Gaming World, the closest thing the industry had to a mature journal of record, came at this game with knives out. In a two-stars-out-of-five review, Tom Chick said that “you’ll spend a lot of time fumbling in limbo, wandering aimlessly, trying to trigger whatever unknowable act will end the time block.” Okay — but it’s very hard to reconcile this criticism with the same magazine’s four-and-a-half star, “Editor’s Choice”-winning review of Grim Fandango. In my experience at least, aimless wandering and unknowable acts are far more of a fact of life in that game than in Gabriel Knight 3, which does a far better job of telling you what your goals are from story beat to story beat.

What might be going on here? To begin with, we do have to factor in that LucasArts had historically enjoyed better reviews and the benefit of more doubts than Sierra, whose adventure games came more frequently but really did tend to be rougher around the edges in the aggregate. Yet I don’t think that explains the contrast in its entirety. The taste-makers of mainstream gaming were still in a bargaining phase when it came to adventure games in 1998, still trying to find a place for them amidst all the changes that had come down the pipe since id Software unleashed DOOM upon the world. That bargaining had been given up as a lost cause a year later. The adventure game, said the new conventional wisdom, was dead as a doorknob, and it wasn’t coming back. A pack mentality kicked in and everyone rushed to pile on. It’s a disconcerting, maybe even disturbing thing to witness, but such is this thing we call human nature sometimes. If the last few years of our more recent social history tell us anything, it is that cultural change can burst upon the scene with head-snapping speed and force to make yesterday’s conventional wisdom suddenly beyond the pale today.

Adventure games would soon disappear entirely from the catalogs of the major publishers and from the tables of contents of the magazines and websites that followed them. In a rare sympathetic take on the genre’s travails, the website Gamecenter wrote just after the release and less than awe-inspiring commercial performance of Gabriel Knight 3 that “now it seems people want more action than adventure. They would rather run around in short shorts raiding tombs than experience real stories.” This was the true nub of the issue, for all that the belittling tone was no more necessary here than when it was directed in the opposite direction. People just wanted different things; a player of Gabriel Knight 3 was not inherently more or less smart, wise, or culturally sophisticated than a player of Starcraft or Unreal Tournament.

So, then, at the risk of stating the obvious, the core problem for the adventure genre was a mismatch between the desires of the majority of gamers at the turn of the millennium and the things the adventure game could offer them. The ultimate solution was for the remaining adventure fans to get their own cottage industry to make for them the games that they enjoyed, plus their own media ecosystem to cover them, replete with sympathetic critics who wanted the same things from gaming that their readers did. That computer gaming as a whole could sustain being siloed off into parallel ecosystems was a testament to how much bigger the tent had gotten over the course of the 1990s. But as of 1999, the siloing hadn’t quite happened yet, leaving a game like Gabriel Knight 3 trapped on the stage of an unfriendly theater, staring down an audience who were no longer interested in the type of entertainment it was peddling. While the game was still in development, Jane Jensen had mused about the controversial elements that may have helped to get it funded: “I guess the worst case would be that no one would care, or even notice.”

The worst case came true. Gabriel Knight 3 became its woebegone genre’s sacrificial lamb, controversial only for daring to exist at all as an ambitious adventure game in 1999. It deserved better, for reasons which I shall now go into.

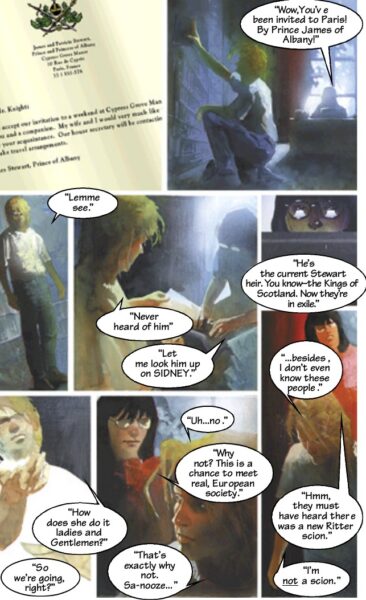

This final Sierra adventure game opens with something else that was not long for this world in 1999: a story setup that’s conveyed in the manual — or rather in an accompanying comic book — instead of in a cutscene. Four years on from their hunt for werewolves in Gabriel Knight 2, Gabriel and his assistant Grace Nakimura are asked to come to the Paris mansion of one Prince James, a scion of the Stuart line that once ruled Scotland and England. After they arrive, the good prince explains that he needs their help to protect his infant son from “Night Visitors” — i.e., vampires. Gabriel and Grace agree to take on the task, only to fail at it rather emphatically; the baby is kidnapped out from under their noses that very night. But Gabriel does manage to give chase, tracking the men or monsters who have absconded with the infant to the vicinity of Rennes-le-Château. Not sure how to proceed from here, he checks into a hotel in the village. The game proper begins the next morning.

At breakfast, he learns that a tour group of treasure hunters has also just arrived at the hotel, all of them dreaming of the riches that are purported to be hidden somewhere in or near the village. In addition to the fetching French tour guide Madeline (to whom Gabriel reacts in his standard lecherous fashion), there are Emilio, a stoic Middle Easterner; Lady Lily Howard and Estelle Stiles, a British blue-blood and her companion; John Wilkes, an arrogant, muscle-bound Aussie; and Vittorio Buchelli, an irritable Italian scholar. To this cast of characters worthy of an Agatha Christie novel we must add Gabriel’s old New Orleans running buddy Detective Frank Mosely, who, in a coincidence that would cause Charles Dickens to roll over in his grave, just happens to have joined this very tour group to try his hand at treasure hunting. Each member of the group has his or her own theory about the real nature of the treasure and how to find it, leaving Gabriel to try to sort out which ones really are the hopeless amateurs they seem to be and which ones have relevant secrets to hide, possibly involving the kidnapping which brought him here.

Anyone who has played the first two Gabriel Knight games will be familiar with this one’s broad approach to its story. It takes place over three days, each of which is divided up into a number of time blocks. Rather than running on clock time, the game runs on plot time: the clock advances only when you’ve fulfilled a set of requirements for ending a time block. Grace arrives at the hotel on the evening of the first day. Thereafter, you control her and Gabriel alternately, just as in Gabriel Knight 2, with Gabriel’s sections leaning harder on conversations and practical investigation, while Grace delves deep into the lore and conspiracy theories of Rennes-le-Château. Don’t let the fact that the whole game is compressed into just three days fool you: they’re three busy days (and nights), busier than any three days could reasonably be in real life.

In this article, I won’t say anything more about the mystery of Rennes-le-Château. For the time being, you’ll just have to trust me when I tell you that it’s an endlessly fascinating rabbit hole. In fact, it fascinates on two separate levels: that of the tinfoil-hat theories themselves, and the meta-level of how they came to find such purchase here in this real world of ours, which is — spoiler alert! — actually not controlled by secret cabals of Knights Templar and the like. I’ll be exploring these subjects in some articles that will follow this one. It’s a digression from my normal beat, but one that I just can’t resist; I hope you’ll wind up agreeing with me that it was well worth it.

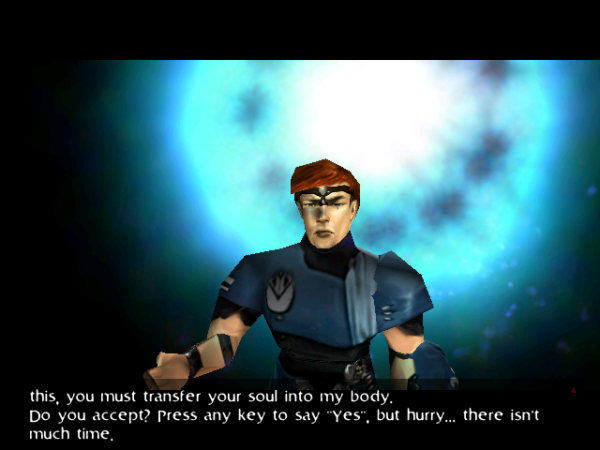

Today, though, let me tell you about some of the other aspects of this game. One of Jane Jensen’s greatest talents as a writer is her skill at evoking a sense of place, whether her setting be Louisiana, Bavaria, or now southern France. If you ask me, this game is her magnum opus in this sense. The 3D graphics here are pretty crude — far from state of the art even by the standards of 1999, never mind today. Characters move more like zombies or robots than real people and look like collections of interchangeable parts crudely sewn together. Gabriel’s hair looks like an awkwardly shaped helmet that’s perpetually in danger of falling right off his head, while trees and plants are jagged-edged amalgamations of pixels that look like they could slice him right open if he bumped into them. And yet darned if playing this game doesn’t truly feel like exploring a sun-kissed village on the edge of the French Riviera. The screenshots may not come off very well in an article like this one, but there’s an Impressionistic quality (how French, right?) to the game’s aesthetics that may actually serve it better than more photo-realistic graphics would. When I think back on it now, I do so almost as I might a memorable vacation, the kind whose contours are blended and softened by the soothing hand of sentiment. If a good game is a space where you want to go just to hang out, then Gabriel Knight 3 is a very good game indeed.

The geography is fairly constrained, meaning you’ll be visiting the same places again and again as the plot unfolds. Far from a drawback, I found this oddly soothing too. I mentioned Agatha Christie earlier; let me double-down on that reference now, and say that the geography is tight enough to remind me of a locked-room cozy mystery. The fact that you’re staying in a hotel with a gaggle of tourists only enhances the feeling of being on a virtual holiday. Playing this game, you never sense the stress and conflict and exhaustion that were so frequently the lot of its developers. Call it one more way in which Gabriel Knight 3 is kind of miraculous; most games reflect the circumstances of their creation much more indelibly.

I suppose it could be considered a problem with Gabriel Knight 3 as a piece of fiction that the setting comes off so bucolic when the stakes are meant to be so high. But I don’t care. I like it here; I really like it.

Meet the story where it lives and let it unfold at its own pace, and you’ll be amply rewarded. Both the backstory of the historical conspiracy and the foreground plot with which it becomes intertwined, about finding the vampiric kidnappers, become riveting. I often play games on the television in the living room while my wife Dorte reads or crochets or does something else, popping up from time to time with a comment, usually one making fun of whatever nerdy thing I happen to be up to tonight. But Gabriel Knight 3 grabbed her too, something that doesn’t happen all that often. She had to go off to a week-long course just as I was getting close to the end. She informed me in no uncertain terms that I was not allowed to finish without her, because she wanted to see how it ended as well. Trust me when I tell you that that is really saying something.

The 3D engine that powers all of this is one of a goodly number of alternative approaches to the traditional point-and-click adventure that appeared as the genre was flailing against the dying of the mainstream light, aimed at helping it to feel more in tune with the times and, in some cases, making it a more friendly fit with alternative platforms like the Sony PlayStation. Few of these reinventions make much of a case for their own existence in my opinion, but the G-Engine is an exception. It’s a surprisingly effective piece of kit. Instead of relying on fixed camera angles, as Grim Fandango does in its 3D engine, Gabriel Knight 3 gives you a free-floating camera that you can move about at will. The environment fills the whole screen; there are no fixed interface elements. Clicking on a hot spot brings up a context-sensitive menu of interaction possibilities. And naturally, you can delve into an inventory screen to look at and combine the items you’re carrying, or to snatch them up for use out in the world. I really, really like the system, which genuinely does add something extra that you wouldn’t get from 2D pixel graphics. You can look up and down, left and right, under and on top of things. A room suddenly feels like a real space, full of nooks and crannies to be explored.

Admittedly, the setup is kind of weird on a conceptual level, in that you’re doing all of this exploration while Gabriel or Grace, whichever one you happen to be controlling, is standing stock still. This game, in other words, lends fresh credence to Scott Adams’s age-old conception of the player of an adventure game being in command of a “puppet” that does her bidding. Here you’re a disembodied spirit who does all the real work, pressing Gabriel or Grace into service only when you have need of hands, feet, or a mouth. You can even “inspect” an object in the room without their assistance — doing so shows it to you in close-up — although you do need them to help you “look,” which elicits a verbal description from your puppet. Gabriel Knight 3 doesn’t take place in a contiguous world; discrete “rooms” are loaded in when you direct your puppet to cross a boundary from one to another. Nevertheless, some of the rooms can be quite large. When you’re out and about on the streets of Rennes-le-Château, for example, the camera might be a block away from Gabriel or Grace, well out of his or her line of sight. It’s odd to think about, but it works a treat in practice.

One of the strangest things about the G-Engine is how the camera seems to have a corporeal form. You can get it hung up behind objects like this bench.

The G-Engine doesn’t add much in the way of emergent possibility. Reading between the lines of some of the reviews, one can’t help but sense that some critics thought the switch to 3D ought to make Gabriel Knight 3 play more like Tomb Raider — and who knows, perhaps this was even envisioned by the developers as well at one time. The game we have, however, is very much an adventure game of the old school, a collection of set-piece puzzles with set-piece solutions, with a set-piece plot that is predestined to play out in one and only one way. Some alternative solutions are provided, even some optional pathways and puzzles that you can engage with for extra points, but there’s no physics engine to speak of here, and definitely no possibility to do anything that Jane Jensen never anticipated for you to do.

That said, there are a few places where the game demands timing and reflexes, especially at the climax. These bits aren’t horrible, but they aren’t likely to leave you wishing there were more of them either. In the end, they too are set-piece exercises, more Dragon’s Lair than Tomb Raider.

Erik Wolpaw and Chet Faliszek wrote Gabriel Knight 3 into gaming history for all the wrong reasons via their website Old Man Murray. They created fictional teenage personas for themselves, Erik being a “fat, girl-looking boy” and Chet being a kid who “likes Ministry and not much else.” How meta, right?

We can’t avoid it anymore, my friends. It’s impossible to discuss Gabriel Knight 3′s puzzles in any depth without addressing the elephant — or rather the cat-hair mustache — that’s been in the room with us this whole time. The uninitiated among you, assuming there are any, will require a bit of explanation.

During the burgeoning years of the World Wide Web, many gaming sites popped up to live on the hazy border between fanzines and professional media organs. One of these went for some reason by the name of Old Man Murray, a place for irreverent piss takes on the games that Computer Gaming World was covering with more earnestness and less profanity. Erik Wolpaw, one of the proprietors, took exception to one particular puzzle that crops up fairly early on in Gabriel Knight 3. He vented his frustration in a… a column, I guess we can call it?… published on September 11, 2000 — i.e., ten months after the game’s release, and well after its lackluster commercial fate had already been decided.

Gabriel needs to get his hands on some form of transportation in order to explore the countryside around Rennes-le-Château. Unfortunately, the motorbike rental lot right next door to the hotel mostly offers only sissy-looking mopeds of a sort that he wouldn’t be caught dead riding. The sole exception is a gleaming Harley-Davidson — but it has been reserved, by, of all people, his old buddy Mosely. Gabriel must engage in an extended round of subterfuge to pretend to be Mosely and secure the bike. This will turn out to involve, among other things, stealing the poor fellow’s passport and concocting a disguise for himself that involves masking tape, maple syrup, and a stray tuft of cat hair. I’ll let Erik tell you more about it. (The bold text below is present in the original.)

Dumb as your television enjoying ass probably is, you’re smarter than the genius adventure gamers who, in a truly inappropriate display of autism-level concentration, willingly played the birdbrained events. Permit me to summarize:

- Gabriel Knight must disguise himself as a man called Mosley [sic] in order to fool a French moped rental clerk into renting him the shop’s only motorcycle.

- In order to construct the costume, Gabriel Knight must manufacture a fake moustache. Utilizing the style of logic adventure game creators share with morons, Knight must do this even though Mosely does not have a moustache.

- So in order to even begin formulating your strategy, you have to follow daredevil of logic Jane Jensen as she pilots Gabriel Knight 3 right over common sense, like Evel Knievel jumping Snake River Canyon. Maybe Jane Jensen was too busy reading difficult books by Pär Lagerkvist to catch what stupid Quake players learned from watching the A-Team: The first step in making a costume to fool people into thinking you’re a man without a moustache, is not to construct a fake moustache.

- Still, you might think that you could yank some hair from one of the many places it grows out of your own body and attach it to your lip with the masking tape in your inventory. But obviously, Ms. Jensen felt that an insane puzzle deserved a genuinely deranged solution. In order to manufacture the moustache, you must attach the masking tape to a hole at the base of a toolshed then chase a cat through the hole. In the real world, such as the one that stupid people like me and Adrian Carmack use to store our televisions, this would result in a piece of masking tape with a few cat hairs stuck to it, or a cat running around with tape on its back. Apparently, in Jane Jensen’s exciting, imaginative world of books, masking tape is some kind of powerful neodymium supermagnet for cat hair.

- Remember how shocked you were at the end of the Sixth Sense when it turned out Bruce Willis was a robot? Well, check this out: At the end of this puzzle, you have to affix the improbable cat hair moustache to your lip with maple syrup! Someone ought to give Jane Jensen a motion picture deal and also someone should CAT scan her brain.

A penetrating work of satire for the ages this column is not, but it nevertheless went viral, until it seemed to be absolutely everywhere on the Internet. In an ironic, backhanded way, Gabriel Knight 3′s cat-hair mustache puzzle became one of the most famous puzzles in all of adventure-gaming history, right up there with the Babel Fish in The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy or Monkey Island’s Monkey Wrench. It became so famous that it has its own Wikipedia page today. At the same time, it became Exhibit Number One in the burgeoning debate over Why Adventure Games Died. Right up to this day, whenever talk turns to the genre’s fall from grace at the end of the twentieth century, a reference to the cat-hair mustache cannot be long in coming. For a considerable number of people today, Gabriel Knight 3 is not a game about vampires or the source material of The Da Vinci Code before Dan Brown discovered it; it’s a game about a cat-hair mustache.

So, what is a Gabriel Knight 3 apologist like myself supposed to do with this? First, let me acknowledge that this is not a great puzzle in strictly mimetic terms, in that it’s impossible to take seriously as a part of the game’s fiction. Setting aside all of the other improbable steps Gabriel has to go through, he steals and defaces — more on the latter in a moment — his good friend’s passport in order to work the scam. All of this instead of just, you know, asking his buddy to help him out. (Mosely is gruff on the outside, but he’s a good egg underneath, as Gabriel knows better than anyone.) Or he could just suck it up and ride a moped for a few days, given that the fate of an innocent baby and who knows what else may depend on it.

Of course, Gabriel Knight 3 is hardly the only adventure game that makes sociopathic behavior a staple of its puzzle tree. This is the root of the genre’s centrifugal pull toward comedy, which almost invariably injects a patina of goofiness even into allegedly serious games like this one. Stuff like this is more naturally at home in a game like Monkey Island. But leave it entirely out of any sort of adventure, and you run the risk of having a game without enough gameplay. If we aren’t afraid of a little bit of whataboutism, we might defend the adventure game by noting here that it’s hardly the only genre whose gameplay is frequently at odds with its fiction: think of putting saving the world on hold in order to hunt down lost pets and carry out a hundred other piddling side-quests in a CRPG, or researching the same technologies over and over from scratch in an RTS campaign. I’ll leave you to decide for yourself how compelling such a defense is.

For what it’s worth, there are reports that this puzzle was not in Jane Jensen’s original design, that it was swapped in late in the day in place of another one that had proved impractical to implement. Rest assured that you won’t catch me calling it a great puzzle, either in the context of this game or of adventure history.

But here’s the thing: mimesis aside, it’s nowhere near as terrible a puzzle as the one that our friend Erik describes either. I played this game a few months ago for the first time, knowing vaguely that it included an infamous puzzle involving a cat-hair mustache — how could I not? — but knowing nothing of the specifics. I went in fully expecting the worst, keeping in mind the design issues I remembered from the first two Gabriel Knight games. I was therefore surprised by how smoothly — and, yes, even enjoyably — the whole puzzle played out for me. Perhaps I was helped by the knowledge I brought with me into the game, but I never had the feeling that I was relying on it, never felt that I couldn’t have progressed without it. There are two hugely important mitigating factors which Erik neglects to mention.

The first is that there actually is a logic to Gabriel making a mustache for himself to imitate the clean-shaven (more or less) Mosely. He thinks that the facial hair will disguise the very different facial bone structures of the two men. Therefore he draws a mustache onto Mosely’s passport photo with a marker — how would you like to have a friend like him? — to complete the deception.

The second factor is more thoroughgoing: the player is guided through all of the steps quite explicitly by Gabriel himself. (Who’s the puppet now, right?) In addition to “Look” and “Inspect,” many hot spots pop up a handy light-bulb icon when you click them: “Think.” These provide vital guidance on, well, what your character is thinking — or rather what Jane Jensen is thinking, what avenues she expects you to explore to advance the story. It’s not a walkthrough — what fun would that be? — but it does give you the outlines of what you’re trying to accomplish. In this case, looking carefully at and “thinking” about all of the objects involved turn a puzzle that truly would be absurdly unfair without this extra information into one that’s silly on the face of it, yes, but pretty good fun all the same. I’ve ranted plenty over bad adventure-game puzzles in the past, the kind where you have no clue what the game wants you to do or how it wants you to do it. This is not one of those. This puzzle doesn’t deserve the eternal infamy in which Old Man Murray draped it.

In point of fact, Gabriel Knight 3 is a major leap forward over the first two games in terms of pure design. Although it’s not trivial to solve by any means, nor does it seem to hate its player in the way of so many older Sierra games. The “Think” verb is one example. And for another one: once you solve the cat-hair-mustache-puzzle, get on your ill-gotten Harley, and start visiting the places around Rennes-le-Château, you can start to ask the game to show you where you still need to accomplish things in your current time block; this alone does much to alleviate the sense of “fumbling around in limbo,” as Tom Chick described it in Computer Gaming World. I don’t know whether the more soluble design of this game is a result of Jane Jensen improving her craft, unsung heroes on the team she worked with, or possibly even directives that came down from the dreaded upper management. I just know that it’s really, really nice to see — nice to be surprised by a game that turns out to be better than its reputation.

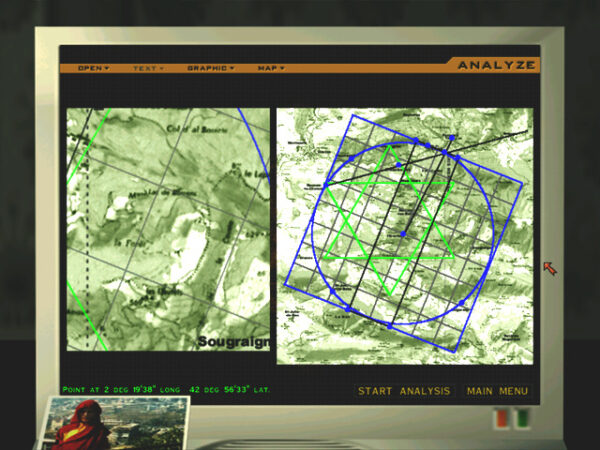

Solving the Le Serpent Rouge puzzle. Jane Jensen cribbed all this business about “sacred geometries” from the book The Tomb of God, which in turn borrowed it from Renaissance and Early Modern hermetic philosophy. (Johannes Kepler was very big on this sort of thing when he wasn’t developing the first credible model of our heliocentric solar system.) It may be nonsense, but it’s wonderfully evocative nonsense when it’s embedded in a story like this one.

The other puzzles here are a commodious grab bag of types. A few of them are every bit as silly as the cat-hair mustache, but most of them are more pertinent to the mysteries you’re actually trying to solve. The most elaborate of them all is a whole chain of puzzles that become Grace’s principal focus over the second and third days, and that are almost as well-remembered within hardcore adventure circles today as the cat-hair mustache is outside of them. The Le Serpent Rouge puzzle sequence takes its name from a 1967 poem by an anonymous author that has become an indelible part of the conspiracy lore surrounding Rennes-le-Château. The reliably bookish Grace has to ferret out its coded meanings, verse by verse, using a variety of software tools on her laptop computer. Some reviewers have called it the best adventure-game puzzle of all time.

For my part, I can’t go quite that far. Like everything else in the G-Engine, the software Grace uses is more of a veneer over the set-piece design than a true simulation. At several stages, I more or less just clicked on things until the game told me I had it right. But if it has its limitations as a set of pure puzzles, Le Serpent Rouge succeeds brilliantly as interactive drama. You’re fully invested by the time it comes along, and the buzz you get as you close in on the heart of the mystery, step by step, is not to be dismissed lightly. In a more just world it would be these puzzles rather than the cat-hair-mustache one that have taken a place in mainstream-gaming lore. For they show just how exciting and gripping smart, textured, context-appropriate adventure-game puzzles can be.

Much the same sentiment can be applied to Gabriel Knight 3 as a whole, a rare Sierra adventure game that I find to be underrated rather than overrated. I’ve not always been so kind toward Sierra’s games, as many of you know all too well. But almost twenty years on, just before they turned the lights out for good, they finally got everything right. This game is my favorite of the entire Sierra catalog. It’s the antithesis of Ultima IX, as high of a note to go out on as that game was a low one. Let’s hear it for lost causes and eleventh-hour miracles.

I have to admit that my experience with Gabriel Knight 3 has to some extent caused me to reevaluate the whole series of which it is a part. Bloody-minded iconoclast that I am, I find that I have to rank the games in reverse chronological order, the opposite of the typical fan’s ordering. I still can’t get fully behind Gabriel Knight I, even when I try to separate the story and setting from my nightmares about searching for a two-pixel-wide snake scale in a Bayou swamp and tapping out nonsensical codes on a bongo drum. Gabriel Knight 2, though… that really is an edge case for me. I still have my share of quibbles with its design, but its flaws are certainly less egregious than those of its predecessor, even as it has stuck in my memory in a way that very few of the narrative-oriented games which I’ve played for these histories have been able to do. Both the second and the third games make me feel emotions that aren’t primary-colored, that are more textured and complex than love and hate, fight and flight. And that is nothing to be sneezed at in the videogame medium.

So, readers, I think I have to put both Gabriel Knight 2 and 3 into my personal Hall of Fame. It was a long time coming for the former, but I did come around to old Gabe and Gracie eventually. It’s only too bad that their story had to end here, just when it was starting to get juicy.

Did you enjoy this article? If so, please think about pitching in to help me make many more like it. You can pledge any amount you like.

Sources: The book Gabriel Knight 3: Prima’s Official Strategy Guide by Rick Barba and Jane Jensen: Gabriel Knight, Adventure Games, Hidden Objects by Anastasia Salter. Computer Gaming World of February 1999, June 1999, and April 2000; Game Developer of June 2000; PC Zone of July 1998; Sierra’s newsletter InterAction of Spring 1999.

Online sources include Adventure Gamer’s interview with Gabriel Knight 3 design assistant Adam D. Bormann, Women Gamers’s interview with Jane Jensen, the vintage GameSpot review of Gabriel Knight 3, the Old Man Murray column discussed in the article, and a designer diary that Jane Jensen wrote for GameSpot during the game’s development.

Where to Get It: Gabriel Knight 3: Blood of the Sacred, Blood of the Damned is available as a digital purchase at GOG.com.

1998 Ebook!

Hi, folks…

Just a quick note to inform you that the ebook for 1998 is now available on the usual page. I’m sorry this was so long in coming. I owe a huge thanks to my hiking buddy Stefaan Rillaert, who adapted Richard Lindner’s original scripts to run on Linux instead of Windows.

We’ve elected to make the books available in .epub format only going forward. The .mobi format has been deprecated for some years now, and all but the oldest Kindle e-readers should have received software updates in 2022 to let them handle .epub files natively. If you are stuck with an extremely old Kindle, you can use Calibre to convert .epub files to .mobi on your computer. I hope this won’t be too much of an inconvenience.

Now that we’ve got the tool chain sorted, new ebooks should be appearing on a more timely basis. Thank you for your patience, and enjoy the 1998 book!

Did you enjoy this article? If so, please think about pitching in to help me make many more like it. You can pledge any amount you like.

Ultima IX

Years ago, [Origin Systems] released Strike Commander, a high-concept flight sim that, while very entertaining from a purely theoretical point of view, was so resource-demanding that no one in the country actually owned a machine that could play it. Later, in Ultima VIII, the company decided to try to increase their sales numbers by adding action sequences straight out of a platform game to their ultra-deep RPG. The results managed to piss just about everyone off. With Ultima IX: Ascension, the company has made both mistakes again, but this time on a scale that is likely to make everyone finally forget about the company’s past mistakes and concentrate their efforts on making fun of this one.

— Trent C. Ward, writing for IGN

Appalling voice-acting. Clunky dialog-tree system. Over-simplistic, poorly implemented combat system. Disjointed story line… A huge slap in the face for all longtime Ultima fans… Insulting and contemptuous.

— Julian Schoffel, writing from the Department of “Other Than That, It Was Great” at Growling Dog Gaming

The late 1990s introduced a new phenomenon to the culture of gaming: the truly epic failure, the game that failed to live up to expectations so comprehensively that it became a sort of anti-heroic legend, destined to be better remembered than almost all of its vastly more playable competition. It’s not as if the bad game was a new species; people had been making bad games — far more of them than really good ones, if we’re being honest — for as long as they had been making games at all. But it took the industry’s meteoric expansion over the course of the 1990s, from a niche hobby for kids and nerds (and usually both) to a media ecosystem with realistic mainstream aspirations, to give rise to the combination of hype, hubris, excess, and ineptitude which could yield a Battlecruiser 3000AD or a Daikatana. Such games became cringe humor on a worldwide scale, whether they involved Derek Smart telling us his game was better than sex or John Romero saying he wanted to make us his bitch.

Another dubiously proud member of the 1990s rogue’s gallery of suckitude — just to use some period-correct diction, you understand — was Ultima IX: Ascension, the broken, slapdash, bed-shitting end to one of the most iconic franchises in all of gaming history. I’ve loved a handful of the older Ultimas and viewed some of the others with more of a jaundiced eye in the course of writing these histories, but there can be no denying that these games were seminal building blocks of the CRPG genre as we know it today. Surely the series deserved a better send-off than this.

As it is, though, Ultima IX has long since become a meme, a shorthand for ludic disaster. More people than have ever actually played it have watched Noah Antwiler’s rage-drenched two-hour takedown of the game from 2012, in a video which has itself become oddly iconic as one of the founding texts (videos?) of long-form YouTube game commentary. Meanwhile Richard Garriott, the motivating force behind Ultima from first to last, has done his level best to write the aforementioned last out of history entirely. Ultima IX is literally never mentioned at all in his autobiography.

But, much though I may be tempted to, I can’t similarly sweep under the rug the eminently unsatisfactory denouement to the Ultima series. I have to tell you how this unfortunate last gasp fits into the broader picture of the series’s life and times, and do what I can to explain to you how it turned out so darn awful.

Al Remmers, the man who unleashed Lord British and Ultima upon the world, is pictured here with his wife.

The great unsung hero of Ultima is a hard-disk salesman, software entrepreneur, and alleged drug addict named Al Remmers, who in 1980 agreed to distribute under the auspices of his company California Pacific a simple Apple II game called Akalabeth, written by a first-year student at the University of Texas named Richard Garriott. It was Remmers who suggested crediting the game to “Lord British,” a backhanded nickname Garriott had picked up from his Dungeons & Dragons buddies to commemorate his having been born in Britain (albeit to American parents), his lack of a Texas drawl, and, one suspects, a certain lordly manner he had begun to display even as an otherwise ordinary suburban teenager. Thus this name that had been coined in a spirit of mildly deprecating irony became the official nom de plume of Garriott, a young man whose personality evinced little appetite for self-deprecation or irony. A year after Akalabeth, when Garriott delivered to Remmers a second, more fully realized implementation of “Dungeons & Dragons on a computer” — also the first game into which he inserted himself/Lord British as the king of the realm of Britannia — Remmers came up with the name of Ultima as a catchier alternative to Garriott’s proposed Ultimatum. Having performed these enormous semiotic services for our young hero, Al Remmers then disappeared from the stage forever. By the time he did so, he had, according to Garriott, snorted all of his own and all of the young game developer’s money straight up his nose.

The Ultima series, however, was off to the races. After a brief, similarly unhappy dalliance with Sierra On-Line, Garriott started the company Origin Systems in 1983 to publish Ultima III. For the balance of the decade, Origin was every inch The House That Ultima Built. It did release other games — quite a number of them, in fact — and sometimes these games even did fairly well, but the anchor of the company’s identity and its balance sheets were the new Ultima iterations that appeared in 1985, 1988, and 1990, each one more technically and narratively ambitious than the last. Origin was Lord British; Origin was Ultima; Lord British was Ultima. Any and all were inconceivable without the others.

But that changed just a few months after Ultima VI, when Origin released a game called Wing Commander, designed by an enthusiastic kid named Chris Roberts who also had a British connection: he had come to Austin, Texas, by way of Manchester, England. Wing Commander wasn’t revolutionary in terms of its core gameplay; it was a “space sim” that sought to replicate the dogfighting seen in Star Wars and Battlestar Galactica, part of a sub-genre that dated back to 1984’s Elite. What made it revolutionary was the stuff around the sim, a story that gave each mission you flew meaning and resonance. Gamers fell head over heels for Wing Commander, enough so to let it do the unthinkable: it outsold the latest Ultima. Just like that, Origin became the house of Wing Commander and Ultima — and in that order in the minds of many. Now Chris Roberts’s pudgy chipmunk smile was as much the face of the company as the familiar bearded mien of Lord British.

The next few years were the best in Origin’s history, in a business sense and arguably in a creative one as well, but the impressive growth in revenues was almost entirely down to the new Wing Commander franchise, which spawned a bewildering array of sequels, spin-offs, and add-ons that together constituted the most successful product line in computer gaming during the last few years before DOOM came along to upend everything. Ultima produced more mixed results. A rather delightful spinoff line called The Worlds of Ultima, moving the formula away from high fantasy and into pulp adventure of the Arthur Conan Doyle and H.G. Wells stripe, sold poorly and fizzled out after just two installments. The next mainline Ultima, 1992’s Ultima VII: The Black Gate, is widely regarded today as the series’s absolute peak, but it was accorded a surprisingly muted reception at the time; Charles Ardai wrote in Computer Gaming World how “weary gamers [are] sure that they have played enough Ultima to last them a lifetime,” how “computer gaming needs another visit to good old Britannia like the movies need another visit from Freddy Krueger.” That year the first-person-perspective, more action-oriented spinoff Ultima Underworld, the first project of the legendary Boston-based studio Looking Glass, actually sold better than the latest mainline entry in the series, another event that had seemed unthinkable until it came to pass.

Men with small egos don’t tend to dress themselves up as kings and unironically bless their fans during trade shows and conventions, as Richard Garriott had long made a habit of doing. It had to rankle him that the franchise invented by Chris Roberts, no shrinking violet himself, was by now generating the lion’s share of Origin’s profits. And yet there could be no denying that when Electronic Arts bought the company Garriott had founded on September 25, 1992, it was primarily Wing Commander that it wanted to get its hands on.

So, taking a hint from the success of not only Wing Commander but also Ultima Underworld, Garriott decided that the mainline games in his signature series as well had to become more streamlined and action-oriented. He decided to embrace, of all possible gameplay archetypes, the Prince of Persia-style platformer. The result was 1994’s Ultima VIII: Pagan, a game that seems like something less than a complete and total disaster today only by comparison with Ultima IX. Its action elements were executed far too ineptly to attract new players. And as for the Ultima old guard, they would have heaped scorn upon it even if it had been a good example of what it was trying to be; their favorite nickname for it was Super Ultima Bros. It stank up the joint so badly that Origin chose toward the end of the year not to even bother putting out an expansion pack that its development team had ready to go, right down to the box art.

The story of Ultima IX proper begins already at this fraught juncture, more than five years before that game’s eventual release. The team that had made Ultima VIII was split in two, with the majority going to work on Crusader: No Remorse, a rare 1990s Origin game that bore the name of neither Ultima nor Wing Commander. (It was a science-fiction exercise that wound up using the Ultima VIII engine to better effect, most critics and gamers would judge, than Ultima VIII itself had.) Just a few people were assigned to Ultima IX. An issue of Origin’s internal newsletter dating from February of 1995 describes them as “finishing [the] script stage, evaluating technology, and assembling a crack development team.” Origin programmer Mike McShaffry:

Right after the release [of Ultima VIII], Origin’s customer-service department compiled a list of customer complaints. It weighed about ten pounds! The Ultima IX core team went over this with a fine-toothed comb, and we decided along with Richard that we should get back to the original Ultima design formula. Ultima IX was going to be a game inspired by Ultimas IV and VII and nothing else. When I think of that game design I get chills; it was going to be awesome.

As McShaffry says, it was hoped that Ultima IX could rejuvenate the franchise by righting the wrongs of Ultima VIII. It would be evolutionary rather than revolutionary, placing a modernized gloss on what fans had loved about the games that came before: a deep world simulation, a whole party of adventurers to command, lots and lots of dialog in a richly realized setting. The isometric engine of Ultima VII was re-imagined as a 3D space, with a camera that the player could pan and zoom around the world. “For the first time ever, you could see what was on the south and east side of walls,” laughs McShaffry. “When you walked in a house, the roof would pop off and you could see inside.” Ultima IX was also to be the first entry in the series to be fully voice-acted. Origin hired one Bob White, an old friend with whom Richard Garriott had played Dungeons & Dragons as a teenager, to turn Garriott’s vague story ideas into a proper script for the voice actors to perform.

Garriott himself had been slowly sidling back from day-to-day involvement with Ultima development since roughly 1986, when he was cajoled into accepting that the demands of designing, writing, coding, and even drawing each game all by himself had become unsustainable. By the time that Ultima VII and VIII rolled around, he was content to provide a set of design goals and some high-level direction for the story only, while he busied himself with goings-on in the executive suite and playing Lord British for the fans. This trend would do little to reverse itself over the next five years, notwithstanding the occasional pledge from Garriott to “discard the mantle of authority within even my own group so I can stay at the designer level.” (Yes, he really talked like that.) This chronic reluctance on the part of Ultima IX’s most prominent booster to get his hands dirty would be a persistent issue for the project as the corporate politics surrounding it waxed and waned.

For now, the team did what they could with the high-level guidance he provided. Garriott had come to see Ultima IX as the culmination of a “trilogy of trilogies.” Long before it became clear to him that the game would probably mark the end of the series for purely business reasons, he intended it to mark the end of an Ultima era at the very least. He told Bob White that he wanted him to blow up Britannia at the conclusion of the game in much the same way that Douglas Adams had blown up every possible version of the Earth in his novel Mostly Harmless, and for the same reason: in order to ensure that he would have his work cut out for him if he decided to go back on his promise to himself and try to make yet another sequel set in Britannia. By September of 1996, White’s script was far enough along to record an initial round of voice-acting sessions, in the same Hollywood studio used by The Simpsons.

But just as momentum seemed to be coalescing around Ultima IX, two other events at Origin Systems conspired to derail it. The first was the release of Wing Commander IV: The Price of Freedom in April of 1996. Widely trumpeted as the most expensive computer game yet made, the first with a budget that ran to eight digits, it marked the apex of Chris Roberts’s fixation on making “interactive movies,” starring Mark Hamill of Star Wars fame and a supporting cast of Hollywood regulars acting on a real Hollywood sound stage. But it resoundingly failed to live up to Origin’s sky-high commercial expectations for it; at three times the cost of Wing Commander III (which had also featured Hamill), it generated one-third as many sales. This failure threw all of Origin Systems into an existential tizzy. Roberts and few of his colleagues left after being informed that the current direction of the Wing Commander series was financially untenable, and everyone who remained behind wondered how they were going to keep the lights on now that both of Origin’s flagship franchises had fallen on hard times. The studio went through several rounds of layoffs, which deeply scarred the communal psyche of the survivors; Origin would never fully recover from the rupture, never regain its old confident swagger.

Partially in response to this crisis, another project that bore the name of Ultima saw its profile elevated. Ultima Online was to be the fruition of a dream of a persistent multiplayer fantasy world that Richard Garriott had been nursing since the 1980s. In 1995, when rapidly spreading Internet connectivity combined with the latest computer hardware were beginning to make the dream realistically conceivable, he had hired Raph and Kristen Koster, a pair of Alabama graduate students who were stars of the textual-MUD scene, to come to Austin and build a multiplayer Britannia. Ultima Online had at first been regarded more as a blue-sky research project than a serious effort to create a money-making game; it had seemed the longest of long shots, and was barely tolerated on that basis by the rest of Origin and EA’s management.

But the collapse of the industry’s “Siliwood” interactive-movie movement, as evinced by the failure of Wing Commander IV, had come in the midst of a major commercial downturn for single-player CRPGs like the traditional Ultimas as well. Both of Origin’s core competencies looked like they might not be applicable to the direction that gaming writ large was going. In this terrifying situation, Ultima Online began to look much more appealing. Online gaming was growing apace alongside the young World Wide Web, even as the appeal of Ultima Online’s new revenue model, whereby customers could be expected to pay once to buy the game in a box and then keep paying every single month to maintain access to the online multiplayer Britannia, hardly requires further clarification. Ultima Online, it seemed, might be the necessary future for Origin Systems, if it was to have a future at all. These incipient ideas were given a new impetus over the last four months of 1996, when two other massively-multiplayer-online-role-playing games — a term coined by Richard Garriott — were launched to a cautiously positive reception. This relative success came even though neither 3DO’s Meridian 59 nor Sierra’s The Realm was anywhere near as technically and socially sophisticated as the Kosters intended Ultima Online to be.

By the beginning of 1997, the Ultima Online developers were closing in on a wide-scale beta test, the last step before their game went live for paying customers. Rather cheekily, they asked the fans who had been following their progress closely on the Internet to pony up $5 each months in advance for the privilege of becoming their guinea pigs; cheeky or not, tens of thousands of fans did so. This evidence of pent-up demand convinced the still-tiny team’s managers to go all-in on their game. In March of 1997, the nine Ultima Online people were moved into the office space currently occupied by the 23 people who were making Ultima IX. The latter were ordered to set aside what they were working on and help their new colleagues get their MMORPG into shape for the beta test. In the space of a year, Ultima Online had gone from an afterthought to a major priority, while Ultima IX had done precisely the opposite. Although both games were risky projects, it looked like Ultima Online might be the better match for where gaming was going.

The conjoined team got Ultima Online to beta that summer and into boxes in stores that September, albeit not without a certain degree of backbiting and infighting. (The Ultima Online people regarded the Ultima IX people as last-minute jumpers on their bandwagon; the Ultima IX people were equally resentful, suspecting — and not without some justification — that their own project would never be restarted, especially if the MMORPG took off as Origin hoped it would.) Although dogged throughout its early years by technical issues and teething problems of design, the inevitable niggles of a pioneer, Ultima Online was soon able to attract a fairly stable base of some 90,000 players, each of whom paid Origin $10 per month to roam the highways and byways of Britannia with others.

It became a vital revenue stream for a studio that otherwise didn’t have much of anything going for it. The same year as Ultima Online’s launch, Wing Commander: Prophecy, an attempt to reboot the series for this post-Chris Roberts, post-interactive-movie era, was released to sales even worse than those of Wing Commander IV, marking the anticlimactic end of the franchise that had been the biggest in computer gaming just a few years earlier. Any petty triumph Richard Garriott might have been tempted to feel at having seen his Ultima outlive Wing Commander was undermined by the harsh reality of Origin’s plight. The only single-player games now left in development at the incredible shrinking studio were the Jane’s Longbow hardcore helicopter simulations, entries in yet another genre that was falling on hard commercial times.

Electronic Arts was taking a more and more hands-on role as Origin’s fortunes declined. A pair of executives named Neil Young and Chris Yates had been parachuted in from the Silicon Valley mother ship to become Origin’s new General Manager and Chief Technical Officer respectively. Much to the old team’s surprise, they opted to restart Ultima IX in late 1997. They read the massive success of the CRPG-lite Diablo as a sign that the genre might not be as dead to gamers as everyone had thought, especially if it was given an audiovisual facelift and, following the example of Diablo, had its gameplay greatly simplified. A producer named Edward Alexander Del Castillo was hired away from Westwood Studios, where he had been in charge of the mega-selling Command & Conquer series of real-time-strategy games. If anyone could figure out how to make the latest single-player Ultima seem relevant to fans of more recent gameplay paradigms, it ought to be him.

What with the ongoing layoffs and other forms of attrition, fewer than half of the 23 people who had been working on Ultima IX prior to the Ultima Online interregnum returned to the project. Those who did sifted through the leavings of their earlier efforts, trying to salvage whatever they could to suit Del Castillo’s new plans for the project. He re-imagined the game into something that looked more like the misbegotten Ultima VIII than the hallowed Ultima VII. The additional party members were done away with, as was the roving camera, and the visuals and interface came to mimic third-person action games like the hugely popular Tomb Raider. Del Castillo convinced Richard Garriott to come up with a new story outline in which Britannia didn’t get destroyed, an event which might now read as confusing, given that people would presumably still be logging into Ultima Online to adventure there after this single-player game’s release. In the new script, as fleshed out once again by Bob White, the player’s goal would be to become one with the villainous Guardian, who would turn out to be the other half of himself, and rise as one being with him to a higher plane of existence; thus the “ascension” of the eventual subtitle. It felt like the older games in the way it flirted with spirituality, for all that it did so a bit clumsily. (Garriott stated in a contemporaneous interview that “I’m enamored with Buddhism right now,” as if it was a catchy tune he’d heard on the radio; this isn’t the way spirituality is supposed to work.)

In May of 1998, Origin brought the work in progress to the E3 trade show. It did not go well. The old-school fans were appalled by the teaser video the team brought with them, featuring lots of blood-splattered carnage choreographed to a thrash-metal soundtrack, more DOOM than Ultima. Del Castillo got defensive and derisive when confronted with their criticisms, making a bad situation worse: “Ultimas are not about stick men and baking bread. Ultimas are about using the computer as a tool to enhance the fantasy experience. To take away the clumsy dice, slow charts and paper and give you wonderful gameplay instead. They were never meant to mimic paper RPGs; they were meant to exceed them.” In addition to being a straw-man argument, this was also an ahistorical one: like all of the first CRPGs, Richard Garriott’s first Ultima games had been literal, explicit attempts to put the tabletop Dungeons & Dragons game he loved on a computer. Internet forums and Usenet message boards burned with indignation in the weeks and months after the show.

Those who could abandoned the increasingly dysfunctional ship. Bob White bailed for John Romero’s new company Ion Storm, where he became a designer on Deus Ex. Then Del Castillo was fired, thanks to “philosophical differences” with Richard Garriott. Lead programmer Bill Randolph recalls the last words Del Castillo said to him on the day he left: “They don’t care about the game. They’re just going to shove it out the door unfinished.”

Garriott announced, not for the first time, that he intended to step in and take a more hands-on role at this juncture, but that never amounted to much beyond an unearned “Director” credit. “You know, he had a lot of other obligations, and he had a lot going on, and a lot of other interests that he was pursuing too,” says Randolph by way of apologizing for his boss. Be that as it may, Garriott’s presence on the org chart but non-presence in the office resulted in a classic power vacuum; everyone could see that the game was shaping up to be hot garbage, but no one felt empowered to take the steps that were needed to fix it. Turnover continued to be a problem as Origin continued to take on water. Few of the people left on the team had any experience with or emotional connection to the previous single-player Ultima games.

Del Castillo’s ominous prophecy came true on November 26, 1999, after a frantic race to the bottom, during which the exhausted, demoralized team tried to hammer together a bunch of ill-fitting fragments into some semblance of a playable game in time for EA’s final deadline. They met the deadline — what other choice did they have? — but the playable game eluded them.

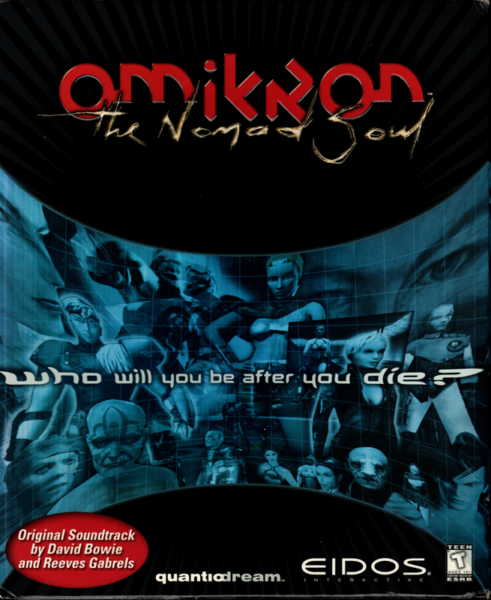

I don’t want to spend a lot of time here excoriating Ultima IX in detail, the way I did Omikron: The Nomad Soul in my very last article. I nominated Omikron for Worst Game of 1999, but Ultima IX has run away with that prize. Although I found Omikron to be deliriously lousy, it was at least lousy in a somewhat interesting way, the product of a distinctive if badly misguided vision. Ultima IX, alas, doesn’t have even that much going for it. Whatever original creative vision it might once have evinced has been so thoroughly ground away by outside pressures and corporate interference that it’s not even fun to make fun of. As far as kind words go, all I can come up with is that the box looks pretty good — a right proper Ultima box, that is — and some of the landscape vistas are impressive, as long as you don’t spoil the experience by trying to do anything as you’re looking at them. Everything else is pants.

Imagine the worst possible implementation of every single thing Ultima IX tries to do and be, and you’ll have a reasonably good picture of what this game is like. Even 26 years later, it remains a technical disaster: crashing constantly, full of memory leaks that gradually degrade performance as you play. Characters and monsters have an unnerving habit of floating in the air, their feet at the height of your eyes; corpses — and not undead ones — sometimes inexplicably keep on fighting instead of staying put on the ground (or in mid-air, as the case may be). These things ought to be funny in a “so bad it’s good” kind of way, but somehow they aren’t. Absolutely nothing about this game is entertaining — not the cutscenes that were earmarked for an earlier incarnation of the script only to be shoehorned into this one, not the countless other parts of the story that just don’t make any sense. Nothing feels right; the physics of the world are subtly off even when everything is ostensibly working correctly. The fixed camera always seems to be pointing precisely where you don’t want it to, and combat is just bashing away on the mouse button, an action which feels peculiarly disconnected from what you see your character doing onscreen.

Of course, one can make the argument that Ultima wasn’t really about combat even in its best years; Ultima VII’s combat system is almost as bad as this one, and that hasn’t prevented that game from becoming the consensus choice for the peak of the entire series. What well and truly pissed off the series’s hardcore fan base back in the day was how badly this game fails as an Ultima. A game that was once supposed to correct the ill-advised misstep that had been Ultima VIII and mark a return to the franchise’s core values managed in the end to feel like even more of a betrayal than its predecessor. This final installment of a series famous for the freedom it affords its player is a rigidly linear slog through underwhelming plot point after underwhelming plot point. Go to the next city; perform the same set of rote tasks as in the last one; rinse and repeat. If you try too hard to do something other than that which has been foreordained for you, you just end up breaking the game and having to start over.