In the late 1970s Anne Westfall, a mother, housewife, and divorcee in her early thirties, started attending Santa Rosa Junior College. With her children “old enough to take care of themselves,” she was looking for a new direction in her life. She sampled a bit of everything on the college’s menu, but fell in love with computer programming via a course in BASIC. More programming courses followed. She became so good at it so quickly that when some members of the faculty were contacted by a local civil-engineering company that was looking to hire programmers for a new software division they hooked her up with a job. Just like that she had a career; she spent the next two years writing programs for surveyors and subdivision planners on the TRS-80.

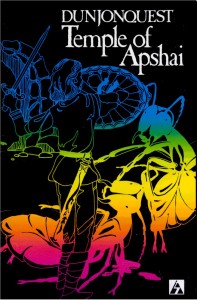

At the West Coast Computer Faire of March 1980, fate placed her company’s booth next to that of Automated Simulations of Temple of Apshai and DunjonQuest fame. She got to talking with Automated’s co-founder and primary game designer, Jon Freeman, and a spark both creative and romantic was kindled. Before meeting Freeman computer games had never even occurred to her as an interest, much less a career. She vaguely knew of some housed on some large computer systems to which she had access, and had played Space Invaders a few times at a pizza parlor, but that was about it. Yet Freeman apparently made one hell of an advocate. Not only did she and he become an item, but just five months after meeting her he convinced her to quit her secure job to come program games for Automated Simulations. Soon after they were married.

The marriage has survived to this day, but the new job proved more problematic. Westfall was forced to work as a so-called “maintenance programmer,” tweaking and maintaining the DunjonQuest engine. She also found herself at the epicenter of a power struggle of sorts between Freeman and his founding partner, Jim Connelley. From the time of their first game, Starfleet Orion back in 1978, the two men had fallen into an equitable division of roles. Freeman, who had spent years studying and writing about tabletop-game design but did not program, designed the games; Connelley, a professional programmer for years before Automated’s founding, implemented them. Even as the company grew in the wake of Temple of Apshai‘s success and other designers and programmers came aboard, the basic division of labor remained: Freeman in charge of the creative, Connelley in charge of the technical. From the start Connelley had focused on developing a reusable engine for the DunjonQuest line, written in BASIC for maximum portability and maintainability and capable of running on virtually any computer with at least 16 K of memory. But now, inspired by Westfall’s talent, by newer machines like the Atari 400 and 800, and by newer iterations of the CRPG concept like Ultima and Wizardry, Freeman was getting antsy. Automated’s games were being left behind, he said. He pushed to abandon BASIC and rewrite everything from scratch in assembly language, and to stop targeting a one-size-fits-all lowest-common-denominator machine. Connelley flatly refused, preferring to continue churning out more scenarios using the same old engine. Finally, at the end of 1981, it all devolved into litigation, which ended with Freeman and Westfall, along with other partisans from their camp, walking away. (For what it’s worth, Freeman’s camp ultimately proved to be in the right. Plummeting sales of Automated’s increasingly archaic-looking games forced a major change in direction within a year of the split, including the adoption of the much catchier name Epyx and a new focus on flashy games for next-generation platforms like the Commodore 64. But that’s a story for another time…)

Freeman and Westfall decided to form their own little development group, the cleverly titled Free Fall Associates, to develop games and publish them through others. They would stay small to avoid a repeat of the power struggles at Automated, and write exactly the games they wanted for the platform they wanted: the Atari 800, the most audiovisually advanced 8-bit computer on the market. They would work as partners, as Freeman had in the beginning with Connelley — only now Westfall could assume the programmer’s role. Seeing a divide between slow-paced, ugly, off-putting strategy games and flashier but vapid action fare, they decided to try to make games that slotted in between: fast-paced and aesthetically pleasing but with an element of depth.

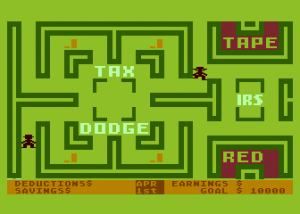

They took pride in making sure their first game was nothing like those Freeman had designed for Automated Simulations. Tax Dodge was a maze game that took advantage of the Atari’s graphics and sound — but don’t call it a Pac-Man clone or even variant lest Freeman, who railed against the unoriginal arcade clones that still littered the bestseller charts, get very huffy with you. The maze now spanned many screens, smoothly scrolling with the player, an effect that would have been very difficult to manage on the more limited hardware of, say, the Apple II. This gave a quality of exploration, of discovery as the player charted the maze. Rather than ghosts, the player must avoid five sinister IRS agents; rather than gobble pills, she collects cash. Finding an accountant in the maze yields a precious tax shelter. It was a theme near and dear to the heart of Freeman, whose capsule biographies in his games never failed to mention his belief in libertarianism and anarcho-capitalism. Indeed, Freeman was among if not the first designer to sneak political statements into his games. (You may remember his 1980 game Rescue at Rigel, which set players on a hostage-rescue mission against a thinly disguised Ayatollah Khomeini, from an earlier article on this site.)

Tax Dodge made little commercial impression, for which Freeman later blamed the fact that the Atari’s demographics skewed much younger than those of the Apple II and TRS-80, the machines on which Automated had largely concentrated their efforts. Most potential players, he argued, missed the satire that was so much of the fun. Still, it also couldn’t have helped that the game was distributed by a tiny publisher called Island Graphics, who lacked the wherewithal to get the game the sort of prominent advertising and feature reviews that were becoming increasingly important as the software industry steadily professionalized. Maybe this freelance-developer thing wasn’t going to be that easy after all. But then Trip Hawkins and Electronic Arts came calling.

Given that Freeman was one of the few prominent designers not bound by contract to another publisher at the moment, Free Fall was an obvious target for Hawkins in his quest for “software artists.” But they were also a good fit in other ways. If you were reminded of Hawkins’s mantra of “simple, hot, and deep” software when I mentioned Free Fall’s determination to bridge the gap between strategy and action, congratulations, you’ve been paying good attention to my recent articles. Clearly these people were all on the same page. Freeman and Westfall were so excited by Hawkins’s vision that they pitched him two radically different ideas for games. One was for a vaguely chess-like strategy game which would erupt into player-against-player action when two pieces met one another on the board; the other was for an infinitely replayable whodunnit mystery. Hawkins was in turn so impressed that he asked for them both for EA’s stable of launch titles, leaving Free Fall with barely six months to make two ambitious games from scratch.

Freeman and Westfall realized they would need some help. They hired a programmer with whom they had worked at Automated Simulations, Robert Leyland, to implement the mystery, freeing Westfall to just work on the strategy game. And they brought in another person they knew from their Automated days, Paul Reiche III, to work with Freeman on the design of both games.

Reiche was just 22, but had already had quite a career in both tabletop and computer games. While still teenagers, he and some friends had written and self-published a series of supplements for Dungeons and Dragons and other tabletop RPGs. Soon after, TSR themselves came calling, to sweep him off to their Wisconsin headquarters to work for them, doing design, writing, illustrating, whatever was needed. He was undoubtedly talented, but it couldn’t have hurt that, being still a teenager at the time of his hiring, he was willing to work cheap. Regardless, it was a dream job for a young D&D nut; he got to share a byline with Gary Gygax himself on the first Gamma World adventure module while just 20 years old.

Reiche first met Freeman at a D&D convention in 1980, where Freeman was demonstrating the DunjonQuest line in an effort to attract the tabletop RPG crowd to this new computerized variant. The two hit it off, and Reiche soon agreed to design a DunjonQuest scenario for Automated, The Keys of Acheron. Then, around the time of Free Fall’s founding, Reiche got himself fired from TSR, according to his telling for raising a stink about the buying of a Porsche as company car for an executive; maybe working cheap was starting to seem less appetizing. He was back in California, studying geology at Berkeley, when Freeman offered him the chance to get back into game design, this time exclusively on the computerized side. He jumped at the chance. Amongst other advantages, it made good sense from a financial perspective. The tabletop RPG industry was already nearing its historical high-water mark by late 1982, but computer games were just getting started.

I’m going to talk in more detail about Archon, the strategy game, today; next time I’ll talk about Murder on the Zinderneuf, the mystery.

Like so much else, much of the fascination amongst gamers with more, shall we say, colorful variants of chess can be traced back to Star Wars — in this case, to the holographic game played between Chewbacca and R2-D2 aboard the Millennium Falcon. That scene, combined with the explosion in popularity of D&D and by extension fantasy of all stripes, led to a minor craze for new variants of chess. Sometimes that meant nothing more than standard chess sets which replaced pawns with goblins and bishops with dragons to give it all a bit of a different flavor. But other people were more ambitious. The movement reached a sort of absurd fruition when Gary Gygax published the rules for Dragonchess in Dragon magazine’s one-hundredth issue in 1985. It featured a three-level board filled with monsters drawn from D&D‘s Monster Manual, with all of the fiddly rules and exceptions you might expect from the man whose signature game (Advanced Dungeons and Dragons) filled three hardbound rulebooks and hundreds of closely typed pages.

At SCA events and similarly minded gatherings, meanwhile, living chess tournaments became more common. These replaced inanimate chess pieces with real people decked out in appropriate costumes, standing on a board that filled an auditorium floor. When two pieces met in one of these games they battled it out there on the board for the crowd’s delight. Sometimes these battles were purely for show, but in other cases players were assigned roles based on their understood talent at fencing, from pawn to queen and king. In these cases the battles were for real — or as real as fake swords allow. The inevitable result, of course, was a very different sort of game, as suddenly a lucky or dogged pawn, or a tired knight, could alter the balance and ruin the most refined of traditional chess strategies. Freeman participated in such a game as a pawn, experiencing the new spontaneity firsthand. (He acquitted himself well, managing to kill a fellow pawn and then fight a knight to a draw — i.e., a mutual kill.) The experience got him thinking about doing something similar on the computer. It seemed like just the sort of mix of strategy and action Free Fall was after.

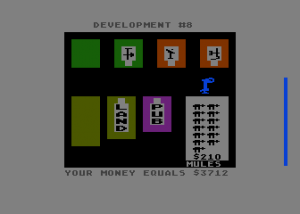

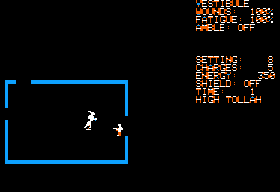

Which is not to say that Freeman and Reiche simply recreated the living-chess experience on the computer. If anything Archon‘s relationship to chess is rather overblown, for Archon is both simpler and more complicated. Movement falls into the former category. Every piece has a maximum number of squares it can move in a turn, and either moves on the ground (meaning it can move only horizontally or vertically and cannot jump pieces) or in the air (meaning it can also move diagonally, and can jump pieces). There is nothing like the complications of, say, the knight in traditional chess. On the other hand, there are more pieces to deal with in Archon, and more places to put them. The board is now 9 X 9 rather than 8 X 8, with the requisite additional two units per side. The larger size was chosen because it fit most neatly on the screen, provided the optimum balance between visibility and strategic possibility, and allowed for three power points to be neatly spaced across the middle of the board. Controlling these three spaces, plus the additional power point located at each edge of the board, wins the game instantly. Alternately, if less strategically, one can win by simply killing all of the opposing player’s units.

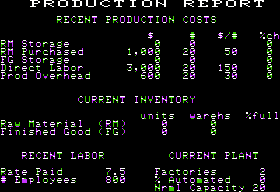

The Archon game board. Note the three power points running down the center. Two more are hidden under the wizard and sorceress on the center-left and center-right squares.

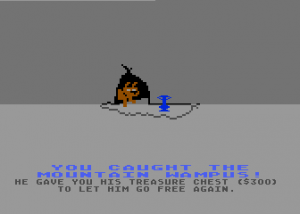

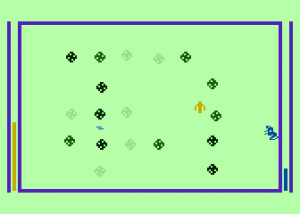

The two opposing forces are no longer mirror images of each other. The game is subtitled The Light and the Dark; the Light side (presumably good) has different units with different combat abilities from the Dark side (presumably evil). Some units use a melee attack; others shoot missiles or fireballs; still others, like the banshee, have an area attack that spreads outward from their person; each side has one unit (the wizard or the sorceress) who can cast a handful of spells once each per game.

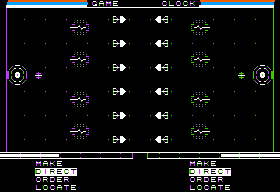

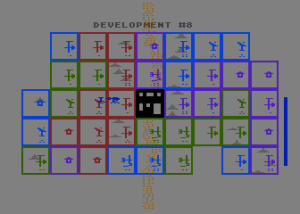

The board at the dark extreme of the luminosity cycle. Note the contrast with the picture above, which shows the cycle at its mid-point.

Of the squares on the board, 25 are always light, 25 always dark. However, the remaining 31, including the three central power points, constantly cycle from light to dark and back. This fact is critical to strategy, because light units gain a big advantage when fighting on light squares, and vice versa. Thus the wise player plans her attacks and retreats, her feints and thrusts, around the ever-changing board. Accidentally leaving a powerful piece exposed on the wrong color of square can lead to the worst sort of self-recrimination when your opponent pounces to take out your golem with her goblin. And yes, just as in the live chess match that inspired Freeman, double kills are possible.

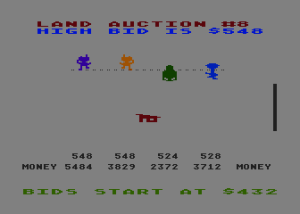

A phoenix (Light) and basilisk (Dark) battle. Because this fight is taking placing on a light square, the phoenix has a huge advantage; note the difference in the life bars at the edge of the screen.

Still other elements of Archon would never have been possible on the tabletop. For instance, the health of each unit is tracked even outside of the combat screen. It takes a few turns to fully recover from a hard fight, meaning a stubborn opponent can kill your wizard just by throwing enough cannon fodder — i.e., goblins — at it turn after turn. The game clearly wants to be played more quickly, more urgently, even (dare I say it?) less strategically than a classic chess match. You find yourself tossing your units into the fray, not pausing to study every option and plan your next several turns in advance. What with the fast pace and the role that reflexes play, playing Archon with another human feels like really going at it, with little of the cool cerebral feel of chess. I have to believe this is intentional, and certainly it’s a more than valid design choice. Indeed, it’s the prime source of Archon‘s appeal in contrast to a game like chess.

That said, there’s one flaw in the strategic game that bothers me enough to really impact my appreciation for the game as a whole. When playing a relatively close game, it’s all too easy to find yourself in an ugly stalemate, in which each player has just a few units left and neither has any incentive to risk any of them by moving them off of favorably colored squares. At this point both sides are just stuck, until someone loses patience at last and attacks the enemy on one of her favorable squares in the face of long odds indeed, all but guaranteeing sacrificing that piece — and, eventually, losing the game — for the sake of just ending the damn thing already. I’m not sure I have any brilliant suggestion of how this could have been fixed — maybe begin to cycle more squares from light to dark as the number of pieces on the board is reduced, thus forcing more dynamism into the game?; maybe add conditions for a chess-style draw? — but I do know that it needed to have been for me to raise my judgment of Archon from “just” a fun and creative effort to the timeless classic many would have me label it. (Then again, it’s possible I’m just missing something strategically obvious. If you have a solution to this dilemma, by all means tell me about it.)

As you might imagine given the time constraints, Westfall, Freeman, and Reiche worked like dogs on Archon even as Freeman and Reiche also labored over Murder on the Zinderneuf. Free Fall had no offices; everything was done out of Freeman and Westfall’s home in Portola Valley, California. Westfall:

We had a tough schedule at first. For six months we didn’t even read a book or go to the movies, and that’s disaster in our house. We basically worked all the time. At meals we were always discussing the games. How to do this, and what to do about that. We worked from the time we got up until all hours of the night. Then we’d get up the next day, grab a cup of coffee, and go back to work.

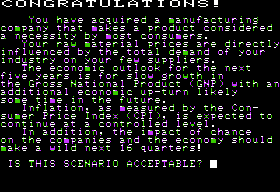

Archon had been envisioned from the beginning as a two-player game. However, just a month before they had to turn over the game, EA begged them to add a single-player option, thus saddling Free Fall with the task of coding a complete AI, in addition to everything else that still had to be done, in one month. With so little time and eager to preserve the game’s fast-paced character, they focused on making an AI that was “fast and decent” rather than “slow and perfect.” As Ozark Softscape did for M.U.L.E., they also made it possible for the AI to play itself, a godsend for shop display windows. And then they added one additional groundbreaking feature that has been little remarked since the game’s release. Freeman:

There’s a built-in, self-adjusting difficulty factor in Archon so that if the computer keeps beating up on you, it will get easier and easier. But most people don’t know that because it goes in little tiny increments. By the time it really starts kicking in, players think, “Oh, I’m just getting better.” Well, they are, partly; but partly it’s because the computer is not being as good. But nobody knows that’s there. It’s not something we advertise, but we were aware of the problem.

Just like chess: how do two unequal players play chess? Well, not very well. And there’s not really a great deal you can do about it. If you start taking pieces away, you change the game so radically that you’re not playing chess anymore. Archon is the same way. So we said, we want to do a game in which we can do that without screwing it up.

This very likely marks the first example of adaptive AI in the commercial game industry, a radical step in the direction of friendlier, more accessible gameplay — and in the direction of Trip Hawkins’s vision of consumer software — that deserves to be celebrated more than it has been. It also kind of leaves you wondering whether any victory over the computer was truly earned, a dilemma familiar to many modern gamers. Ah, well… groundbreaking as Archon‘s adaptive AI is, the game is still best experienced with two players, where it all becomes moot anyway.

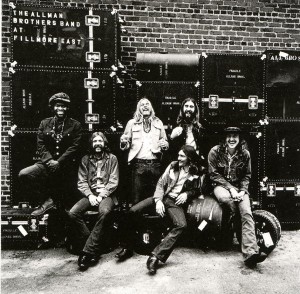

Released in a striking monochrome sleeve that beautifully presented the theme of Light and Dark, Archon struck a major chord with the public. It became the second-best-selling of those seven EA launch titles, behind only Pinball Construction Set. I strongly encourage you to play it, but I’m not going to provide a download here. Free Fall, you see, is still around as at least a semi-going concern and still licensing variants and remakes, and I don’t want to step on any toes. I’m sure you can find the original game on your own if you’re so inclined. The Atari 8-bit incarnation was the first developed and is thus the best reflection of the original vision for the game, although the Commodore 64 port does look nicer. If you do snag one of these versions from somewhere else, maybe think about buying the latest licensed incarnation as well, if for nothing else than to show your appreciation to Freeman and Westfall.

The other Free Fall game amongst those early titles, Murder on the Zinderneuf, didn’t attract anywhere near as much attention as Archon. Yet in its own way it’s every bit as interesting — perhaps even more so if, like me, you like a strong dose of story in your games. We’ll talk about that game, and wrap up the story of Free Fall, next time.

(I’ll include the main sources I used for researching Free Fall in the concluding article.)