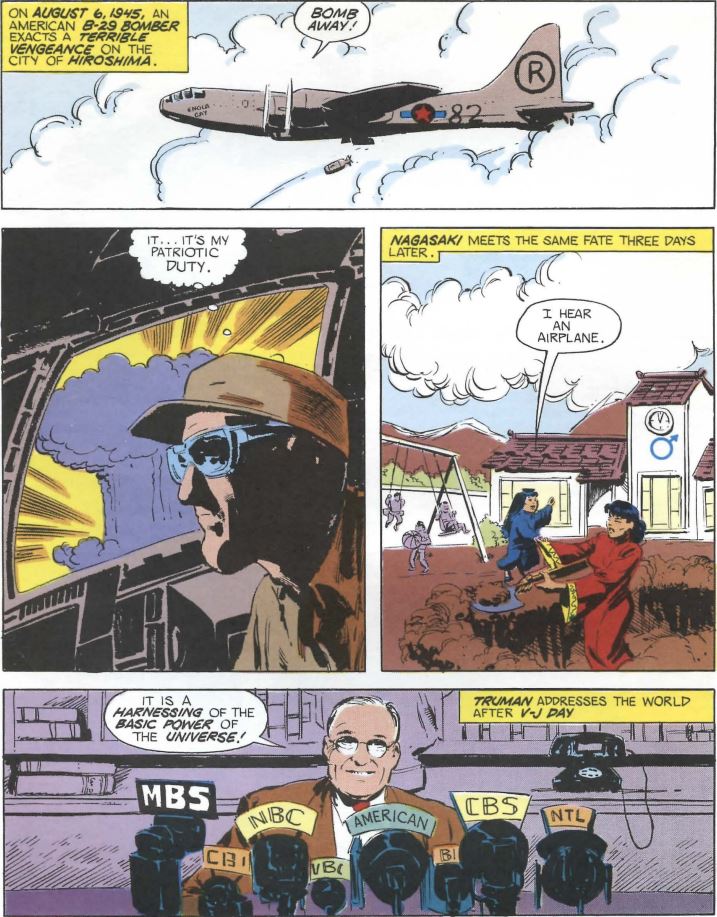

Playground

A set of children's swings moves slowly back and forth in the humid breeze. Behind them stands a long building, its windows hung with flowers and birds folded from colored paper.

Mounds of dirt are heaped around a dark opening to the east. It appears to be a shelter of some kind.

Several small children are happily chasing dragonflies north of the swing set. Turning south, you see a group of adults (schoolteachers, by the looks of them), wearily digging another shelter like the first.

A little girl races between the swings, hot on the trail of a dragonfly. She trips and sprawls across the sand, laughing with hysterical glee. Then she sees you.

At first, you're sure she's going to scream. Her eyes dart back and forth between you and the teachers; you can see a cry forming on her lips.

Suddenly, the umbrella in your hand catches her eye. You watch her expression soften from fear to curiosity.

>examine girl

The girl is a cute four or five years old.

The girl can't keep her eyes off the umbrella.

You've noticed a faint sound coming from somewhere overhead. The girl turns to stare at the sky.

>girl, hello

The girl blinks uncomprehendingly.

The sound overhead grows louder. There's no mistaking the drone of aircraft.

The girl looks at you expectantly and tries to pull you towards the shelter.

Muttering with exasperation, the teachers drop their spades and begin to trudge in the direction of the shelter.

One teacher, a young woman, sees you standing in the sandpile and shrieks something in Japanese. Her companions quickly surround you, shouting accusations and sneering at your vacation shorts. You respond by pointing desperately at the sky, shouting "Bomb! Big boom!" and struggling to escape into the shelter.

This awkward scene is cut short by a searing flash.

On August 6, 1945, a B-29 Superfortress piloted by Colonel Paul Tibbets dropped the second atomic bomb ever to be exploded in the history of the world — and the first to be exploded in anger — on the Japanese city of Hiroshima. Three days later another B-29, piloted this time by Major Charles Sweeney, dropped another — the second and, so far, the last ever to be exploded in anger — on Nagasaki; it’s this event that Trinity portrays in the excerpt above. On August 15, Japan broadcast its acceptance of Allied surrender terms.

The cultural debate that followed, condensed into four vignettes:

In the immediate aftermath of the event, the support of the American public for the bombings that have, according to conventional wisdom, ended the most terrible war in human history is so universal that almost no one bothers to even ask them about it. One of the few polls on the issue, taken by Gallup on August 26, finds that 85 percent support the decision versus just 10 percent opposed. Some weeks later another poll finds that 53.5 percent “unequivocally” support the country’s handling of its atomic arsenal during the war. Lest you think that that number represents a major drop-off, know that 22.7 percent of the total don’t equivocate for the reason you probably think: they feel that the United States should have found some way to drop “many more” atomic bombs on Japan between August 6 and August 15, just out of sheer bloody-mindedness. Newspapers and magazines are filled with fawning profiles of the “heroes” who flew the missions, especially of their de facto spokesman Tibbets, who comes complete with a wonderfully photogenic all-American family straight out of Norman Rockwell. He named his B-29 the Enola Gay after his mother, for God’s sake! Could it get any more perfect? Tibbets and the rest of the Enola Gay‘s crew march as conquering heroes through Manhattan as part of the Army Day Parade on April 6, 1946. The Enola Gay becomes a hero in her own right, with the New York Times publishing an extended “Portrait of a B-29” to tell her story. When she’s assigned along with Tibbets himself to travel to Bikini Atoll to possibly drop the first Operations Crossroads bomb, the press treat it like Batman and his trusty Batmobile going back into action. (The Enola Gay is ultimately not used for the drop. Likewise, Tibbets supervises preparations, but doesn’t fly the actual mission.)

Fast-forward twenty years, to 1965. The American public still overwhelmingly supports the use of the atomic bomb, while the historians regard it as having saved far more lives than it destroyed in ending the war when it did and obviating the need for an invasion of Japan. But now a young, Marxist-leaning economic historian named Gar Alperovitz reopens the issue in his first book: Atomic Diplomacy: Hiroshima and Potsdam. It argues that the atomic bomb wasn’t necessary to end World War II, and, indeed, that President Truman and his advisers knew this perfectly well. It was used, Alperovitz claims, to send a message to the Soviet Union about this fearsome new power now in the United States’s possession. The book, so much in keeping with the “question everything your parents told you” ethos of the burgeoning counterculture, becomes surprisingly popular amongst the youth, and at last opens up the question to serious historiographical debate in the universities.

Fast-forward thirty years, to the mid-1990s. The Smithsonian makes plans to unveil the newly restored Enola Gay, which has spent decades languishing in storage, as the centerpiece of a new exhibit: The Crossroads: The End of World War II, the Atomic Bomb, and the Cold War. The exhibit, by most scholarly accounts a quite rigorously balanced take on its subject matter that strains to address thoughtfully both supporters and condemners of the atomic bombings, is met with a firestorm of controversy in conservative circles for giving a voice to critics of the bombing at all, as well as for allegedly paying too much attention to the suffering of the actual victims of the bombs. They object particularly to the charred relics from Hiroshima that are to be displayed under the shadow of the Enola Gay, and to the quotations from true-blue American heroes like Dwight Eisenhower voicing reservations about the use of the bomb. Newt Gingrich, the newly minted Republican Speaker of the House, condemns the Smithsonian and the director of its National Air and Space Museum, Martin Harwit, as “cultural elites” telling Americans “they ought to be ashamed of their country.” Tibbets, still greeted as a hero in some circles but now condemned as an out-and-out war criminal in others, proclaims the proposed exhibit simply “a damn big insult” whilst reiterating that he feels not the slightest pang of conscience over what he did and sleeps just fine every night. In the end the grander ambitions for the exhibit are scuttled and Harwit harried right out of his job. Instead the Smithsonian sets up the Enola Gay as just another neat old airplane in its huge collection, accompanied by only the most perfunctory of historical context in the form of an atomic-bombing-justifying placard or two.

Fast-forward another ten years. On November 1, 2007, Paul Tibbets dies at the age of 92. The blizzard of remembrances and obituaries that follow almost all feel compelled to take an implicit or explicit editorial position on the atomic bombings, which are as controversial now as they’ve ever been. Conservative writers lay on the “American hero” rhetoric heavily. It’s the liberal ideologues, though, who become most disingenuously strident this time. Many resort to rather precious forms of psychoanalysis in trying to explain Tibbets’s lifelong refusal to express remorse for dropping the bomb, claiming that it means he had either been a sociopath or deeply troubled inside and holding himself together only through denial. They project, in other words, their own feelings toward the attack onto him whilst refusing him the basic human respect of accepting that maybe the position he had steadfastly maintained for sixty years was an honest, considered one rather than a product of psychosis.

If support for the atomic bombings of Japan equals mental illness there were an awful lot of lunatics loose in the bombings’ immediate aftermath. If we could go back and ask these lunatics, they’d likely be very surprised that people are still debating this issue at all today. Well before 1950 the history seemed largely to have been written, the debate already long settled in the form of the neat logical formulation destined to appear in high-school history texts for many decades, destined to be trotted out yet again for the bowdlerized version of the Enola Gay exhibit. Japan, despite being quite obviously and comprehensively beaten by that summer of 1945, still refused to surrender. But then, as the Smithsonian’s watered-down exhibit put it: “The use of the bomb led to the immediate surrender of Japan and made unnecessary the planned invasion of the Japanese home islands. Such an invasion, especially if undertaken for both main islands, would have led to very heavy casualties among American, Allied, and Japanese armed forces, and Japanese civilians.” The bombings were terrible, but much less terrible than the alternative of an invasion of the Japanese home islands, which was estimated to likely cost as many as 1 million American casualties, and likely many times that Japanese.

For a sense of the sheer enormity of that figure of 1 million casualties, consider that it’s very similar to the total of American casualties in both Europe and the Pacific up to the summer of 1945. Thus we’re talking here about a potential doubling of the United States’s total casualties in World War II, and very possibly the same for Japan’s already much more horrific toll. The only other possible non-nuclear alternative would have been a blockade of the Japanese home islands to try to starve them out of the war, a process that could have taken many months or even years and brought with it horrific civilian death and suffering in Japan itself as well as a slow but steady dribble of Allied casualties amongst the soldiers, sailors, and airmen maintaining the blockade. For a nation that just wanted to be done with the war already, this was no alternative at all.

Against the casualties projected for an invasion or even an extended blockade, the 200,000 or so killed in Hiroshima and Nagasaki starts to almost seem minor. I’d be tempted to say that you can’t do this kind of math with human lives, except that we did and do it all the time; see the platitudes about the moderate, unfortunate, but ultimately acceptable “collateral damage” that has accompanied so many modern military adventures. So, assuming we can accept that, while every human life is infinitely precious, some infinities are apparently bigger than others (Georg Cantor would be proud!), the decision made by Truman and his advisers would seem, given the terrible logic of war, the only reasonable one to make… if only this whole version of the administration’s debate wasn’t a fabrication.

No, in truth Truman never had anything like the debate described above with his staffers — unsurprisingly, as the alleged facts on which it builds are either outright false or, at best, highly questionable. Far from being stubbornly determined to battle on to the death, Japan was sending clear feelers through various diplomatic channels that it was eager to discuss peace terms, with the one real stumbling block being the uncertain status under the Allies’ stated terms of “unconditional surrender” of the Emperor Hirohito. Any reasonably perceptive and informed American diplomat could have come to the conclusion that was in fact pretty much the case in reality: that many elements of this proud nation were still in the Denial phase of grief, clinging to desperate pipe dreams like a rescue by, of all people, a Soviet Union that suddenly joined Japan against the West — but, as those dreams were shattered one by one, Japan as a whole was slowly working its way toward Acceptance of its situation. Given these signs of wavering resolution, it seems highly unlikely that an invasion of Japan, should it have been necessary at all, would have racked up 1 million casualties on the Allied side alone. That neat round figure is literally pulled out of the air, from a despairing aside made by Truman’s aging, war-weary Secretary of War Henry Stimson. Army Chief of Staff George Marshall engaged in a similar bit of dead reckoning, based on nothing but intuition, and came up with a figure of 500,000. Others reckoned more in the range of 250,000. The only remotely careful study, the only one based on statistical methods rather than gut feelings, was one conducted by the Army that estimated casualties of 132,500 — 25,000 of them fatalities — for an invasion of Kyushu, 87,500 casualties — 21,000 of them fatalities — if a follow-up invasion of Honshu also became necessary. Of course, nobody really knew. How could they? The only thing we do know is that 1 million was the highest of all the back-of-the-napkin estimations and over four times the military’s own best guess, meaning it’s better taken as an extreme outlier — or at least a worst-case scenario — than a baseline assumption.

The wellspring for the problematic traditional narrative about the use of the atomic bomb is an article which Henry Stimson wrote for the February 1947 issue of Harper’s Magazine. This article was itself written in response to the first mild stirrings of moral qualms that had begun the previous year in the media in response to the publication of John Hersey’s searing work of novelistic journalism Hiroshima. Stimson’s response sums up the entire debate and the ultimate decision to drop the bombs so eloquently, simply, and judiciously that it effectively ended the debate when it had barely begun. The two most salient planks of what’s become the traditionalist view of the bombing — Japan’s absolute refusal to surrender and that lovely, memorable round number of 1 million casualties — stand front and center. This neat version of events would later be enshrined in the memoirs of Truman and his associates.

Yet, as we’ve seen, Stimson’s version of the debate must be, at best, not quite the whole truth. I want to return to it momentarily to examine the biggest lie therein, which I consider to be profoundly important to really understanding the use of the bomb. But first, what of the stories told by those of later generations who would condemn the use of the bomb? They’ve staked various positions over the years, ranging from unsubstantiated claims of racism as the primary motivator to arguments derived from moral absolutism: “One cannot firmly be against any use of nuclear weapons yet make an exception in the case of Hiroshima,” writes longtime anti-nuclear journalist and advocate Greg Mitchell. Personally, I don’t find unnuanced tautologies of that stripe particularly helpful in any situation; there’s always context, always exceptions.

By far the strongest argument made against the use of the atomic bomb is the one that was first deployed by Gar Alperovitz to restart the debate in 1965: that external political concerns, particularly the desire to send a message to the Soviet Union, had as much or more to do with the use of the bomb than a simple desire to end the war as quickly and painlessly as possible. While the evidence isn’t quite as cut-and-dried as many condemners would have it, there’s nevertheless enough fire under this particular smokescreen to make any proponent of the atomic bombing as having merely been doing what was necessary to end the war with Japan at least a bit uncomfortable.

It was the evening of the first day of the Potsdam Conference involving Truman, Stalin, Winston Churchill, and their respective staffs when Truman first got word of the success of the Trinity test. Many attendees remarked the immediate change in his demeanor. After having appeared a bit hesitant and unsure of himself during the first day, he started to assert himself boldly, almost aggressively, against Stalin. Suddenly, noted a perplexed Churchill, “he told the Russians just where they got on and off and generally bossed the whole meeting.” Only when Churchill got word from his own people of the successful test did all become clear: “Now I know what happened to Truman yesterday…”

There follow Potsdam in the records of the administration’s internal discussions a disturbing number of expressions of hopes that the planned atomic bombings of Japan will serve as a forceful demonstration to Stalin that the United States should not be trifled with in the fast-approaching postwar world order. Secretary of State Jimmy Byrnes in particular gloated repeatedly that the atomic bomb should make the Soviets “more manageable” in general; that it would “induce them to yield and agree to our positions”; that it had given the United States “great power.”

But we have to be careful here in constructing a chain of causality. While it’s certainly clear that Truman and many around him regarded the bomb as a very useful lever indeed against increasing Soviet intractability, this was always discussed as simply a side benefit, not a compelling reason to use the bomb in itself. There were, in other words, lots of musing asides, but no imperatives in the form of “drop the bomb so that we can scare the Russians.” Truman’s diary entry after learning of the Trinity test mentions the Soviets only as potential allies against Japan: “Believe Japs will fold up before Russia comes in. I am sure they will when Manhattan explodes over their homeland.”

If we consider actions in addition to words the situation begins to look yet more ambiguous. Prior to Potsdam the United States had been pushing the Soviet Union with some urgency to enter the war against Japan, believing a Soviet invasion of Manchuria would tie down Japanese troops and resources should an American-led home-island invasion become necessary. The Truman administration also believed a Soviet declaration might, just might, provide the final shock that would bring Japan to its senses and cause it to surrender without an invasion. But in the wake of Trinity American diplomats abruptly ceased to pressure their Soviet counterparts. The Soviet Union would declare war at last anyway on August 8 (in between the two atomic bombings), but the United States, once it had the bomb, would seem to have judged that ending the war with the bomb would be preferable for its interests than having the war end thanks to the Soviet Union’s entry. The latter could very well give Stalin postwar justification for laying claim to Manchuria or other Japanese territories, claiming part of the spoils of a war in which the Soviet Union had participated only at the last instant. An additional implicit consideration may have been the conviction of Byrnes and others that it wouldn’t hurt postwar negotiations a bit to show Stalin just what a single American bomber could now do. The realpolitik here isn’t pretty — it seldom is — but what to make of the whole picture is far from clear. The words and actions of Truman and his advisers would seem ambiguous enough to be deployed in the service of any number of interpretations, from condemnations of them as war criminals to assertions that they were simply doing their duty in prosecuting to the relentless utmost of their abilities their war against an implacable enemy. Yes, interpretations abound, most using the confusing facts as the merest of scaffolds for arguments having more to do with ideology and emotion. I won’t presume to tell you what you should think. I would just caution you to tread carefully and not to judge too hastily.

In that spirit, it’s time now to come back to the biggest lie in Stimson’s article. Quite simply, the entire premise of the article is untrue. Actually, there was no debate at all over whether the atomic bomb should be used on Japan.

Really. Nowhere is there any record of any internal debate at all over whether the atomic bomb should be dropped on Japan. There were debates over when it should be used; on which cities it should be used; whether the Japanese should be warned beforehand; whether it should be demonstrated to the Japanese in open country or open ocean before starting to bomb their cities. But no one, no one inside the administration ever even raised the shadow of a suggestion that it should simply be declared too horrible for use and mothballed. Not even among the scientists who built the bomb, many of whom would become advocates in the postwar years for atomic moderation or abolition, is there even a hint of such an idea. Even Niels Bohr, who was frantically begging anyone in Washington who would listen to think about what the bomb might mean to the future of civilization, simply assumed that it would be used as soon as it was ready to end this war; his concern was for the world and the wars that would follow. Interestingly, the only on-the-record questioners of the very idea of using the atomic bomb are a handful from the military who had no direct vote on the strategic conduct of the war in the Pacific, like — even more interestingly — Dwight Eisenhower. Those unnoticed voices aside, the whole debate over the use of the atomic bomb on Japan is largely anachronistic in that nobody making the big decisions at the time ever even thought to raise it as a question. The use of the bomb, now that it was here, was a fait accompli. I really believe that this is a profoundly important idea to grasp. If you insist on seeing this conspicuously missing debate as proof of the moral degradation of the Truman administration, fair enough, have at it. But I see it a little bit differently. I see it as a sign of the difference between peace and war.

The United States has visited war upon quite a number of nations in recent decades, but the vast majority of Americans have never known war — real war, total war, war as existential struggle — and the mentality it produces. I believe that this weirdly asymmetrical relationship with the subject has warped the way many Americans view war. We insist on trying to make war, the dirtiest business there is, into a sanitized, acceptable thing with our “targeted strikes” and our rhetoric about “liberating” rather than conquering, all whilst wringing our hands appropriately when we learn of “collateral damage” among civilians. Meanwhile we are shocked at the brutal lengths the populations of the countries we invade will go to to defend their homelands, see these lengths as proof of the American moral high ground (an Abu Ghraib here or there aside), while failing to understand that what is to us a far-off exercise in communist control or terrorist prevention is to them a struggle for national and cultural survival. Of course they’re willing to fight dirty, willing to do just about anything to kill us and get us out of their countries.

World War II, however, had no room for weasel words like “collateral damage.” It was that very existential struggle that the United States has thankfully not had to face since. This brought with it an honesty about what war actually is that always seems to be lacking in peacetime. If the conduct of the United States during the war in the Pacific was not quite as horrendous as that of Japan, plenty of things were nevertheless done that our modern eyes would view as atrocities. Throughout the war, American pilots routinely machine-gunned Japanese pilots who had bailed out of their stricken aircraft — trained pilots being far, far more precious a commodity to the Japanese than the planes they flew. And on the night of March 9, 1945, American B-29s loosed an incendiary barrage on Tokyo’s residential areas carefully planned to burn as much of the city as possible to the ground and to kill as many civilians as possible in the process; it managed to kill at least 100,000, considerably more than were killed in the atomic bombing of Nagasaki and not far off the pace of Hiroshima. These scenes aren’t what we think of when we think of the Greatest Generation; we prefer a nostalgic Glen Miller soundtrack and lots of artfully billowing flags. Our conception of a World War II hero doesn’t usually allow for the machine-gunning of helpless men or the fire-bombing of civilians. But these things, and much more, were done.

World War II was the last honest war the United States has fought because it was the last to acknowledge, at least tacitly, the reality of what war is: state-sponsored killing. If you’re unlucky enough to lead a nation during wartime, your objective must be to prosecute that war with every means at your disposal, to kill more of your enemy every single day than he kills of your own people. Do this long enough and eventually he will give up. If you have an awesome new weapon to deploy in that task, one which your enemy doesn’t possess and thus cannot use to retaliate in kind, you don’t think twice. You use it. The atomic bomb, the most terrible weapon the world has ever known, was forged in the crucible of the most terrible war the world has ever known. Of course it got used. The atomic bombings of Japan and all of the other terrible deeds committed by American forces in both Europe and the Pacific are not an indictment of Truman or his predecessor Roosevelt or of the United States; they’re an indictment of war. Some wars, like World War II, are sadly necessary to fight. But why on earth would anyone who knows what war really means actually choose to begin one? The collective American denial of the reality of war has enabled a series of elective wars that have turned into ugly, bleeding sores with no clear winners or losers; somehow the United States is able to keep mustering the will to blunder into these things but unable to muster the will to do the ugly things necessary to actually win them.

The only antidote for the brand of insanity that leads us to freely choose war when any other option is on the table is to be forced to stop thinking about it in the abstract, to be confronted with some inkling of the souls we’re about to snuff out and the suffering we’re about to cause. This is one of the services that Trinity does for us. For me, the most moving moment in the entire game is the one sketched out at the beginning of this article, when you meet a sweet little girl who’s about to become a victim of the world’s second atomic-bomb attack. Later — or earlier; chronology is a tricky thing in Trinity — you’ll meet her again, as an old woman, in Kensington Gardens.

>examine woman

Her face is wrong.

You look a little closer and shudder to yourself. The entire left side of her head is scarred with deep red lesions, twisting her oriental features into a hideous mask. She must have been in an accident or something.

A strong gust of wind snatches the umbrella out of the old woman's hands and sweeps it into the branches of the tree.

The woman circles the tree a few times, gazing helplessly upward. That umbrella obviously means a lot to her, for a wistful tear is running down her cheek. But nobody except you seems to notice her loss.

After a few moments, the old woman dries her eyes, gives the tree a vicious little kick and shuffles away down the Lancaster Walk.

That scene breaks my heart every time I read it, and I’m still not entirely sure why.

I like the fact that Trinity goes to Nagasaki rather than Hiroshima. The Hiroshima attack, the more destructive of the two bombings in human lives by a factor of at least two and of course the first, normally gets all of the attention in art and journalism alike. Indeed, it can seem almost impossible to avoid emphasizing Hiroshima over Nagasaki; I’ve done it repeatedly in this article, even though I started out vowing not to. “We are an asterisk,” says Nagasaki sociologist Shinji Takahashi with a certain bitter sense of irony. “The inferior a-bomb city.” Nagasaki wasn’t even done the honor of being selected as a target for an atomic bomb. The B-29 that bombed Nagasaki had been destined for Kokura, but settled on Nagasaki after cloud cover and drifting smoke from a conventional-bombing raid made a drop on Kokura too problematic. An accident of clouds and wind cost 50,000 or more citizens of Nagasaki their lives, and saved the lives of God only knows how many in Kokura. As the Japanese themselves would say, such is karma. And such is the stuff of tragedy.

Jayle Enn

February 13, 2015 at 7:41 pm

Trinity was the first Infocom game I finished without a (hard to find) hint book. I’m not sure if it’s because the puzzles were fairly straightforward, or the writing was so compelling to a teenage me. I think the latter because, decades later, I’ll think unbidden, ‘Her face is wrong’ and relive the awful realization of who that little girl by the swingsets grew up to be.

Jimmy Maher

February 14, 2015 at 11:01 am

I *love* the line “She must have been in an accident or something.” So perfect, so cluelessly contemporary American.

Lisa H.

February 16, 2015 at 8:25 am

I feel dumb – who does the Nagasaki scene girl grow up to be?

Lisa H.

February 16, 2015 at 8:35 am

Never mind; got it now. But I do still feel pretty stupid – especially given the number of times I’ve played through this game – that I never noticed that before.

Ronixis

February 13, 2015 at 7:51 pm

From the survey result, is that actually 22.7% of the remainder (which would be 10.5% of the total respondents) or 22.7% of the total respondents?

Jimmy Maher

February 14, 2015 at 8:48 am

I didn’t write that very well at all. I meant 22.7 percent of the total respondents. Fixed it. Thanks!

Duncan Stevens

February 13, 2015 at 9:31 pm

Agree that there isn’t really a good answer to whether Truman should have dropped the bomb. Having read some of the literature, it does seem to me that the option of demonstrating its use to the Japanese (say, by dropping it on an uninhabited island) before using it on a city deserved more attention than it got. It appears that it was rejected by the committee Stimson chaired for fear that (1) the bomb might not work, emboldening the dead-enders, and (2) telling the Japanese that the bomb was coming might lead them to shift POW camps into the likely targets. I’ve never found either explanation very convincing: (1) while there was some question about whether the plutonium bomb (Fat Man) would work, it was pretty clear that the uranium bomb (Little Boy) would work, and (2) there had already been extensive bombing of Japanese cities, so if Japan was going to move POWs to the cities to deter strikes, it likely would have done so already.

On the other hand, Japan *didn’t* react to Hiroshima by surrendering immediately, so you could argue that the demonstration wouldn’t have accomplished anything. The Rhodes book suggests that three days wasn’t enough time for the relevant decisionmakers to make their choice, and there may be something in that, but I haven’t seen any evidence that unconditional surrender was imminent when the second bomb was dropped. (The book also notes that the regime stacked the deck by, for example, publishing the proposed surrender terms in the newspapers but heavily editing the terms so that they seemed more onerous.)

As for the diplomatic feelers…I’ve never been sure what to think. Mixed messages were being sent, and whether the U.S. should have viewed surrender on acceptable terms as inevitable without the bomb or an invasion isn’t, to my eye, as easy a question as you suggest. Had the Potsdam declaration clearly stated that “unconditional surrender” didn’t mean Hirohito had to go, would that have changed things? Maybe, maybe not. And even if it could be expected that Japan would have gotten there eventually, waiting for that wasn’t a cost-free strategy either; see the sinking of the Indianapolis on July 30.

One other note about the woman in London: consider that the premise of the game as it ultimately plays out is that she will (almost certainly) die in the London attack. I.e., she’ll survive the Nagasaki attack, severely scarred, and live her life only to die in another bombing. Thinking about it that way helps particularize what would, as you note, otherwise be abstract.

Ken Rutsky

February 13, 2015 at 9:49 pm

“As for the diplomatic feelers…I’ve never been sure what to think.”

I seem to remember the diplomatic overtures were made behind the backs of the military command, who were really running the show? Or am I wrong…

Jimmy Maher

February 14, 2015 at 9:21 am

There was definitely a war faction and a peace faction, but I’m not sure I’d characterize it as the latter “going behind the backs” of the former. I believe it was more just a heated internal debate, with resulting mixed signals sent to the outside world.

Duncan Stevens

February 14, 2015 at 3:08 pm

I believe that the Japanese diplomats in question were in Switzerland; they said they had back-channel communications going on with the regime, but it wasn’t 100% clear whether the regime was on board with everything they were saying.

Jeremy Gans

February 14, 2015 at 2:20 am

I read last year that there are a number of Japanese who were bombed in Hiroshima, then shipped off as survivors to Nagasaki (too) soon after. I think they are all dead now, but they were known (and venerated to a degree) in Japan as the ‘twice-bombed.” I remember thinking at the time that the girl in Trinity was also in that category.

(One other thing. It did strike me that she seemed to give up on that umbrella a little too easily, given what it must have meant to her.)

Jimmy Maher

February 14, 2015 at 10:14 am

One other obvious argument against demonstrating the bomb was that, as I alluded to in another comment, the Americans actually only had two of them to hand, and didn’t expect more for several weeks. Thus if you use one as a demonstration and Japan doesn’t respond as you hope you’ve lost one of your two precious bullets.

Truman and Stimnson among others later did claim to have dropped leaflets on Japan warning of the impending attack, but the historical record is unclear a) whether this happened at all or b) whether if it did they were well-enough written and widely-enough distributed to make any realistic difference.

One thing that often goes unreported is that there actually were 23 American prisoners of war in Hiroshima…

A huge part of the “unconditional surrender” situation was dictated by domestic political calculations on Truman’s part. Far from being the “buck stops here” standup decision-maker of popular legend, Truman ran an administration that was in some ways the first of the modern ones, driven very much by polling. His Secretary of State Jimmy Byrnes was a particularly political creature. “Unconditional surrender” was *hugely* popular with the American public, and Truman was very nervous about how it would be received if he suddenly modified that. And he was also concerned that he not appear weak to Stalin.

I would say Japan’s surrender, with or without the bomb, *was* inevitable; it obviously wasn’t going to *win* this war, and the United States obviously wasn’t going to accept anything less. This would have been as obvious to Truman as it is to us. The question, of course, is *when* that surrender would occur.

Truman’s duty as a wartime leader, as I see it, was not to kill Japanese just for the fun of it, but also not to trade even 100,000 Japanese lives for 1 American. That’s harsh, but that’s what war *is*. In waiting around after the first bomb was dropped or hoping that the Soviets’ entry could bring about Japan’s surrender, he would have been doing just that; the Kamikazes would have continued to fly into American ships and the Japanese submarines would have continued to torpedo them (as the fate of the Indianapolis made so clear). This is the reason that at the end of the day I reluctantly and sadly agree with the decision to use the bomb — or at least am unwilling to condemn Truman for it; this is a very, very difficult question for me. I’d a feel a little better about my answer if Truman had also continued to pressure Stalin to come in, and hadn’t gloated so much about the effect the use of the atomic bomb would have on relations with the Soviet Union…

Duncan Stevens

February 14, 2015 at 3:27 pm

When the surrender would occur and on what terms was not clear. The regime pretty much blew off the Potsdam declaration, and while other channels may have been more receptive, there was a lot of uncertainty. As you note, Truman, at that point, wasn’t willing to sacrifice any more American lives in hopes of a less harsh outcome, and continuing to pound Japan with conventional weapons wasn’t going to be cost-free.

It’s not clear to me how big a difference, for Japan, Stalin entering the war earlier would have made, or whether Japan would have surrendered without the use of the bomb. The Soviet Union could roll through Manchuria, but it wasn’t going to be leading an invasion of the main islands. (Did the Soviets even have an amphibious force?)

Jason Dyer

February 14, 2015 at 5:36 pm

I’m not so convinced at the case surrender was inevitable. Even after the two atomic bombs there was a near-coup to prevent a surrender.

http://warhistorian.org/grimsley-coup-what-if.pdf

Ken

February 16, 2015 at 3:02 am

Also often overlooked (or ignored) is that a peace short of unconditional Japanese surrender – either on terms of status quo ante bellum (reset the map to December 5, 1941) or involving Japan giving up a fairly small portion of their prewar conquests in China – would have done nothing more than sow the seeds of the next war, as the fundamental cause of the war -Japan’s dominance by a militaristic government that sought to build a self-sufficient economic empire via fire and sword.

So long as the US owned or was allied with any territory between Asia and Midway Island, the US possessed the strategic position to strangle any Japanese Empire that could ever be, meaning that unless Japan forsook their dreams of such an empire, that empire would only exist as long as the United States allowed it to exist. This was an intolerable situation to the military figures that actually ruled there, so the only real option open was either unconditional Japanese surrender, or another war -just as bad, if not worse- ten or twenty years down the line, exactly as happened with the ill-conceived Versailles treaty that ended WWI.

As for the casualty debate for DOWNFALL, the military planners that formulated the lower figures were ignorant of the quantity of suicide units that Japan had ready for battle. In addition to the famous Kamikaze fighters and less famous “baka” manned cruise missiles, they had large numbers of manned torpedoes (used rather little in the war) ,suicide speedboats (never used operationally), and suicide midget submarines (also never used). Those units alone (which proved very difficult to stop and highly accurate) would have inflicted very heavy casualties among the troopships for the invasion.

Potentially even worse, cyanide pills were manufactured and distributed to civilians in mass numbers (I personally know a woman who still has the one she was given by her mother as a small girl and told to take if the Americans came), which had the potential for mass civilian deaths even without the inevitable collateral damage that would result from any serious fighting.

Jimmy Maher

February 16, 2015 at 7:05 am

As a counterpoint, there were signs of what the military suspected to be weakening resolution that were taken into account. At Okinawa, 7400 soldiers from the garrison actually surrendered — still a small percentage, but a much, much higher number than surrendered in previous campaigns. See George Feifer’s Tennozan: The Battle for Okinawa and the Atomic Bomb for more on the military’s thinking.

While you describe a lot of very sensible reasons for making sure Japan capitulated completely, by 1945 none of that was at all in question within Truman’s administration for the very reasons you state. The only question was whether to accept as a condition the continuing reign of Hirohito as Emperor and to give him immunity to war-crimes charges — and this of course was accepted in the end.

Ken Rutsky

February 13, 2015 at 9:46 pm

Great article, the best in this series so far, and one of the best overall I’ve read on this blog. I really appreciate the sections about the public’s changing view of prosecuting war. “[S]omehow the United States is able to keep mustering the will to blunder into these things but unable to muster the will to do the ugly things necessary to actually win them” is profound, well-put.

I’ve already said it, but thanks so much for these posts. I was a military history nut from a very young age (still am). Reading Hersey’s book in sixth grade (a flea market book seller recommended it to me; I think he found my enthusiasm for the subject a little unsettling) really opened my eyes to a lot of what got left out of all those old history books, glossy atlases and Ballantine paperbacks. Maybe your blog will do the same for someone else.

Jimmy Maher

February 14, 2015 at 9:42 am

Thanks! Even though this is (I believe) the shortest of these articles, it’s the one I struggled with the most. I think I ended up excising almost as much text as I left in. I removed a lot of editorializing, as I think this is a question everyone should probably think about for herself. I have my own view, which probably still does creep through a bit in the article, but I really don’t want to tell you what to think. I suppose that’s kind of exception to my general rule for this blog. Enjoy it while it lasts… ;)

It sounds like we have similar histories. When I was maybe ten or so I discovered a treasure trove in our attic, a bunch of old Military Book Club books on World War II. For the next several years I was known as “the warmonger” within the family. I loved a four-volume series by Edward Jablonski called Airwar most of all. I was particularly fascinated with its vivid descriptions of the carrier battles in the Pacific; I relived them over and over in my imagination, even bought the absurdly complex Avalon Hill wargame Flattop (which I proceeded to get absolutely nowhere with).

At the time I was also a big Star Trek fan, and I kind of conflated the two in my mind. My favorite episodes were not the planetside stories but the ones where the Enterprise would do battle in space and Kirk would command from the bridge with photon torpedoes flying and damage reports coming in. Inevitably, the starship Enterprise led me to the storied World War II aircraft carrier Enterprise. I read The Big E by Edward Stafford several times front to back.

But I think it was another part of Airwar that first began to bring home to me the real meaning of war. Writing about the Naval Battle of Guadalcanal, Jablonski described vividly how the American pilots machine-gunned Japanese troops on the decks of transports and, after those transports were sunk, as they struggled in the water. The carnage was so terrible that many of the pilots threw up in their cockpits, but they kept on pulling their triggers lest those troops make it Guadalcanal and reinforce the Japanese garrison there.

Definitely a needed corrective to my view of war as all glory and excitement and adventure. War is killing. These days I’m very aware of that, and always find myself saying when I open one of those old gung-ho books I used to love, “But you’re making light of killing people!” I don’t judge military-history buffs for the hobby, as I know how compelling it can be, but it’s just not for me anymore.

It sounds like Hiroshima may have been a corrective you could use, and a certain bookstore owner may have been very, very wise to recommend it…

ZUrlocker

February 15, 2015 at 3:26 pm

Yes, enjoyed this post quite a bit. Definitely best of the series. And the comments are also very good reading.

Jeremy Gans

February 14, 2015 at 2:17 am

A terrific post and one I’d been nervous about for personal reasons. I’m an Australian and attended a US summer school (in Paris) in 1994, which I think must have been during the debate about the Smithsonian display. I talked to some Americans about the issue and took what I thought would be a gentle route into the dilemma, saying (not quite truly) “I’m convinced that the US was right to bomb Hiroshima. But I’m not so sure about Nagasaki. Couldn’t they have at least waited a few more weeks to see if the Japanese would surrender?” I’m pretty sure that I was inspired to make that argument by Trinity, which I recall surprised me by taking me to Nagasaki, rather than Hiroshima as I was anticipating. Like you and others, that girl’s wrong face was a lasting image. However, to say the least, my plan for a gentle argument didn’t work. The folks I argued with were incensed by my suggestion and I was incensed that they were incensed. There was some shouting.

Anyway, one thing I am curious about, that you don’t cover here, is the debate the Americans DID have, about what to bomb in Japan, and when, and who. And, to reiterate my question from twenty years ago, what was the rationale (if there was one) for bombing Nagasaki/Kokuru just three days after Hiroshima?

Jimmy Maher

February 14, 2015 at 9:03 am

There was never any proposal or conception that I’m aware of to bomb Japan just twice (or once) and then wait and see what it did in response. The plan was rather to conduct an atomic-bombing *campaign* until Japan surrendered. But the problem was that every bomb was essentially a handmade bespoke piece, quantities of uranium and plutonium were still limited, etc. So it was simple logistics problems that kept more bombs from dropping between August 9 and August 15. I believe the next bomb was actually still at least two weeks away from being ready to go at the time of Japan’s surrender.

The discussions about where to bomb make for a very complicated subject if you drill down into the minutiae. Tokyo was taken off the slate for early targeting right away, partly for humanitarian reasons — the population was *very* densely packed even by Japanese standards — partly out of concern for how it would look to the rest of the world, partly for practical reasons — you might not want to wipe out the seat of government and thus plunge the country into chaos when you hope the government is about to surrender. Otherwise, cities were wanted which had at least some semblance of being of military value — again, largely for political reasons — and, much more cold-bloodedly, that hadn’t been bombed too extensively before, so the damage the atomic bomb did could be better evaluated.

Kyoto actually fit all of these criteria and almost certainly would have been one of the first two targets had not Secretary of War Henry Stimson personally intervened and said, no, we can’t bomb “the Rome of Japan.” A very interesting guy was Stimson…

Andrej Panjkov

February 22, 2015 at 5:01 am

I believe that the ground zero point for Kyoto was going to be the central railyard, which is now a locomotive museum. The prime exhibit there is the Emperor’s official locomotive engine.

Scott Gage

February 16, 2015 at 3:59 am

Great article. Very thought-provoking stuff.

Bit of a typo though:

all whilst ringing our hands appropriately when we learn of “collateral damage” among civilians

That should be “wringing”, unless you have bells for hands :)

Jimmy Maher

February 16, 2015 at 6:40 am

:) Thanks!

Lisa H.

February 16, 2015 at 8:40 am

So aside from me being dense (and posting a comment before I’d even finished reading the article), I do want to say that I found the running motif in the comic of “It’s my patriotic duty” interesting, especially the line here with the hestitation in it, and “I hear an airplane” particularly chilling – so innocent.

Kevin Colyer

March 5, 2015 at 9:27 pm

Very insightful and thoughtful post. I think your comments of the use of the bomb being obvious in the totality of war very interesting and the contrast with post-wwII wars having a strong ring of truth to them.

I have been reading your blog avidly, but this has been the best post (and series). Perhaps there is a history book or two in you?!!!

Ruber Eaglenest

March 27, 2015 at 6:51 am

You said that “That scene breaks my heart every time I read it, and I’m still not entirely sure why.” Well I’m sure it breaks your hearth the second time you play the game, or further revisits to the game. Isn’t Trinity a wonderful game?

There are more emotives moment in the thread of time with that secene. You can save the girl inside in a way but dying in the process, but it is a sweet death.

Martin

July 28, 2016 at 3:14 am

Sorry if this is ignoring the main meat of the article but this is bugging me.In the game sample, you say “girl, hello” and get a blank response because I assume, you are talking in English. So what happens if you try to talk to her in Japanese? Does the game have any options to actually communicating with her?

Jimmy Maher

July 28, 2016 at 7:10 am

Don’t believe so, no.

Gideon Marcus

February 5, 2017 at 2:53 am

Great article. I did not see mention that the casualty predictions were inflated to justify the dropping of the bomb (you say there was no debate at all over the bomb’s use); during my Japanese studies classes, which were largely useless, there was much discussion over that issue.

Speaking of wargames, my wife and I played Operation Olympic, the Avalon Hill simulation of the never-executed invasion of Kyuushuu. It was fascinating battling over cities we had just visited a few months before, including a little village where lives the charming Japanese family that adopted us over the last decade.

I’m glad it wasn’t real….

Wolfeye M.

September 14, 2019 at 11:33 am

I once saw a picture of a woman who “survived” the bombing of either Hiroshima or Nagasaki. Her face was melted, almost like a smear, no eyes, nose, or mouth, nothing that made her recognizable as a human. That description in the game tones it down a lot. I’m not sure how long she lived after they took the picture of her, but part of me hopes it wasn’t very long. I wouldn’t even wish that on my worst enemy, and all she was guilty of was belonging to a country we were at war with. That image sometimes revisits me in my nightmares.

I personally think that dropping the bombs was justifiable, even a sad necessity to end the war as quickly as possible, but… I’ve heard people say it was a GOOD thing. Makes me want to look up that picture of that poor woman and send it to them, let them see the reality of what they’re talking about. But, that’d mean I’d have to see it again.

I just hope cooler heads continue to prevail, and dropping A-bombs in war happens only once in the history of the world.

Lee C.

August 10, 2020 at 4:55 pm

Abu Grahib -> Abu Ghraib

Jimmy Maher

August 12, 2020 at 9:53 am

Thanks!

Ben

July 9, 2022 at 5:53 pm

The End of World II -> The End of World War II

Smithsonian and its director, Martin Harwit -> Smithsonian and the director of its National Air and Space Museum, Martin Harwit

the the United States’s -> the United States’s

in the Kensington Gardens -> in Kensington Gardens

breaks my heart -> [linked video not available anymore]

Jimmy Maher

July 11, 2022 at 1:24 pm

Thanks!

Michael

March 13, 2023 at 10:45 pm

Looking at this from the perspective of today, what chills me most is what you say about the logic of war. If you were right, the it seems like it’s only a matter of time until Russia decides to go ahead and use one or more nuclear warheads in Ukraine, which, for them, is not a proxy war. Certainly Ukraine, if they managed to get hold of one (or somehow kept one hidden away at the end of the Cold War) would have every reason to do so.

Let’s hope the logic of war is more nuanced than it seemed in 2015.